The birth of Dionysus is recounted in various versions, some more fantastical than others. Among these, the most widely accepted narrative tells that Zeus, the king of the gods, approached the mortal woman Semele, daughter of King Kadmos of Thebes, in the guise of a serpent. He showered her with love and affection, courting her patiently over time and slowly winning her heart. At last, they consummated their union, and when Zeus impregnated her, her bedchamber became overgrown with the vines and flowers of Dionysus, while the earth itself rejoiced in celebration. Zeus then revealed his true identity to Semele, promising her that their child would be a god. However, Zeus’s wife, Hera, the queen of the gods, grew jealous. She disguised herself as an old woman and approached Semele, planting seeds of doubt in her mind. Hera suggested that Zeus did not truly love her, insisting that if he really loved her, he would reveal his true, divine form—the one that no mortal had ever seen, which only the gods were permitted to behold. Semele, convinced of Zeus’s love, resisted at first, but Hera persistently urged her to ask Zeus to prove his devotion by showing himself in his full, divine glory. Hera, of course, knew that Zeus’s divine form was so radiant that no mortal could gaze upon it without being incinerated. In other words, Hera knew that if Zeus revealed himself to Semele in this way, it would be fatal.

Semele prayed to Zeus, pleading with him to reveal himself in his true form to prove his love. She even went so far as to say that if he refused, it would mean he did not love her at all. Bound by his word, Zeus granted her wish and appeared before her in his full, divine splendor. Tragically, the intensity of his glory was too much for Semele to bear, for she was only mortal, and the sight of Zeus in his full divine essence reduced her to ashes.

The unborn Dionysus, being immortal, survived the flames. Zeus carefully rescued the fetus from the ashes of his mother and, in an extraordinary act, sewed him inside his own thigh. When the time came, Zeus gave birth from his thigh to his son, Dionysus, the immortal god. Upon his birth, Dionysus bore horns shaped like the crescent moon. The Horai, or “Hours,” goddesses who represent the seasons, crowned him with a wreath of ivy and flowers, and coiled horned serpents around his head. Because Dionysus was born twice—once from the ashes of his mortal mother Semele, and again from the flesh of his immortal father Zeus—he was known by the epithet διμήτωρ (dimetor), meaning “the Twice-Born.”

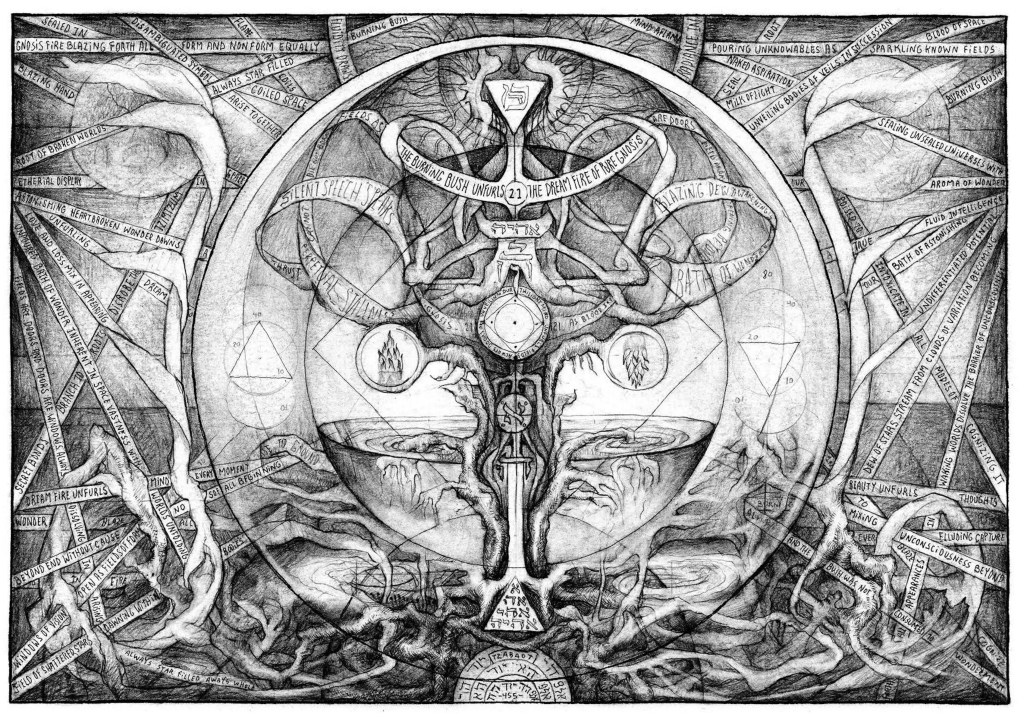

The Zelator, in this narrative, will encounter many signs that can help clarify his program, serving as both a source of motivation and a guiding beacon. A very important element is the indication of Dionysus’ dual birth—from his mother, as much as from Zeus. In this way, he embodies the letter Vav in the Tetragrammaton, the Son of the Great Father and Mother—Chokmah and Binah—who resides in the Air of Tiphareth and the center of Ruach. Surrounded by the active Air element, especially because his mother, Semele, was consumed by the fiery vision of creation, the essence of the Universe—Zeus himself. Similarly to the Archangel Metatron, who acts as an intermediary between the world of man and God, conveying words to humanity as much as they are ready to accept, and serving as a filter to protect human limitations before the sacred and living fire of creation, shielding them from the overwhelming touch of truth that would destroy everything it touches—especially human limited understanding of the Universe and reality. In fact, in this story, the Zelator is not Dionysus, not at all—he is rather Semele, who dared to gaze into the flash of eternal and truthful light of LVX, and was thereby destroyed. But what remains of her is what the Zelator seeks—the purified and elevated essence of his grade, who relentlessly and unconditionally strives for Adonai. This is certainly just a faint glimpse of what awaits the Aspirant upon undertaking the Abramelin operation, and during his withdrawal to perform his Great Work, his most significant task, at the cost of everything he thinks he possesses by then, even at the cost of his own life. His resolve to carry out this operation mirrors the determination of Gautama Buddha, who vowed not to move from his spot until he achieved ultimate Enlightenment. In order for Dionysus to be born, his mother had to be destroyed—his Understanding (Binah) had to be surrendered to the darkness and void of NOX, because his striving must be anything but “his.” It is the striving of the entire Universe, which “only” manifests through him, for which he is the vessel. Through his birth from the ashes of his Mother, he inhabits the Father—the active element of Fire, assuming the activity and essence of the second active element, Air, in the same way the Zelator surpasses the Neophyte’s grasp. The Zelator ignites and agitates their nature through elevated thought—like spreading glowing embers, by means of provocation, doubt, and examination through scientific illuminism. It is precisely this approach that will burn “Semele” and, from her ashes, extract the intrinsic preciousness of the Aspirant, which is directed onward, in a manner that charmingly mirrors and imitates Great Work itself—the one that is yet to be performed in its full and true form. This is the preparation of the Aspirant for what follows, for certainly, the Aspirant will be entirely consumed in the terrible furnace of the Athanor, and nothing that is “he” will remain. The Zelator begins preparations through the study of the Mass of the Holy Ghost, researching and examining this sacred alchemical operation. What is here for discussion are two strategically different models of reaching alchemical gold. The first, in which Nigredo is transformed into Gold, or the Elixir of Wisdom, and which is widely accepted within the occult community today. The second, in which the furnace’s fire serves to burn away rot and actually only expose the same gold that has always existed within the black matter, and which has always been at its core, so here there is no real transformation, but rather the awakening of a dormant nature that has always been there—deep below and deep within.

The Zelator submits every thought, every mental task, every riddle, and story of the mind to the Holy Guardian Angel, and such elevated devotion will find its full manifestation in the grade of the Practicus—a grade that is equally covered by Air, despite its mystery of Water and the magical weapon of the Cup. It is toward this grade that the vast currents of Air will unfold, with every thought directed toward the Holy Angel under the protection of airy Mercury. Here, the essence of Air is somehow supra-elemental—it holds a planetary nuance, which will represent the Practicus’ work in the domains of Dharana and Pratyahara—prepared and solidified as the Zelator, with a peculiar trial, known as the “Temptation of the Sword.”

Thus, the nature of the Dagger is to cut and divide—not merely reality and Air, but the Aspirant. Their experiments dissect and sever their being, splitting body and spirit, as they wonder in which half their true Self resides. And so, as they continue to cut and divide, they realize that another “part” can always be separated, and that no act of cutting will ever reveal their indivisible essence. Only through fire, the flame of knowledge, can they grasp reality as it is. Scientific illumination is a method, not an end; no act of division or intellectual analysis will reveal the place where they are wholly themselves.

The specificity of the Zelator is similar to Dionysus—that they are born twice, as the Angel is “Unborn and Headless.” All of these ideas are something that a Zelator must consider and, through meditation, imbue with meaning in their personal development and life. Dionysus’ double birth represents the Zelator’s journey through the ritual of Tuat, a course through a corridor of darkness, after which they mature on the path of true LVX, but remain far from the brilliance of Knowledge and the Conversation, of which they may only have faint hints and superficial traces.

In practical terms, the Zelator must not allow their experiments in lucid dreaming—and later, as a Practicus, in scrying—to degenerate into mere obsessions or endless, hollow spying into the disintegrating world of their phantasmagorias. Instead, these practices must always be directed toward observation and the search for their Pure Will. They must keep in mind that every vision should lead toward meaning and the discovery of their Angel, even if it appears only as a fleeting flash, a whisper, or a brief outline. Each glimpse, no matter how small, brings them a step closer to their true nature.

Unlike the Neophyte and lucid dreaming, where the emphasis is on the experience of inner reality without it being implemented or imprinted into real life, as well as the phenomena of altered consciousness that is so specific to lucid dreaming, which the Neophyte will carefully experiment with, the Zelator deals with the astral plane, so to speak, from a waking perspective. The emphasis is not on the moment when otherworldly experiences are obtained, no matter how exalted or fascinating they may seem, but rather on the later analysis—when the Aspirant returns to the waking state and the physical plane, and begins to analyze with their mind “that” which was received and expressed through them. Astral experience has one dimension and significance when it is received, and a completely different one when analyzed. Sometimes the Selfhood manifests through a vision of the highest sarcasm or mockery, while at first glance it may seem like a hymn, as entire choirs of angels greet the Zelator in their arrival. The Zelator must learn to use their waking mind to fully discern the vision they received and its message, and to distinguish the nature of the light that passes through them. Just as the Moon reflects the Sun’s light and its form changes every day, so too the Zelator’s conclusion about the nature of the vision is always dependent on one factor that they must always keep in mind— in relation to their Will—whether they know it or not, it must be that Will which they do not know, and nothing else. This analysis must not contain mere gematria and other Qabalistic hints; it must equally contain the linking and discovery of other magical connections that relate the vision to childhood, the present, buried emotions, sexual perversions, and unquenched thirsts in their entire apparatus.

Even though the Zelator knows that every thought of theirs is merely a reflection, and every experience only a projection, they always know that it is a reflection of nothing other than the golden Sun, and their personal, self-sustaining starry fire. In every vision, they must construct a map, with all its streets, secret passages, subway routes, bus lines, and dead ends. They must sketch and depict with their sharp mind the highest orders of angels, as well as seemingly insignificant sylphic fluttering whispers, and always interpret them in the same manner as part of the librettos of a single aria—the dialogue between God and their soul.

There is a specific type of affliction that disrupts the Aspirant’s practice of Yoga, which is the tendency of the mind to become scattered the moment it focuses on the object of meditation, a tendency that particularly affects us and which we will specifically deal with in the instruction for the Practicus grade. But for now, the Zelator’s focus is not on Dharana and Pratyahara, but rather on their younger and duller relatives, Asana and Pranayama—so that, as a Practicus, they can apply these methods properly. Only after the signals and burdens of the body and automatic processes have been mastered can the Aspirant turn to the true task—contemplation and attunement. Only then can we even speak of meditation as such; without mastering Asana and Pranayama, their work is nothing but the mind’s lollygagging, which behaves like a dog chasing its own tail.

Fixed ideas, sudden changes of plans, and drastic life shifts may find their refuge in the sphere of the Zelator’s work. Younger Aspirants may exhibit unexpected and hasty decisions about changing faculties, while slightly older ones may contemplate changing their life’s profession. The decision to change one’s place of residence is not foreign either. However, a dedicated Aspirant will not attribute positive or negative aspects to this, but, in the spirit of scientific illumination, they will approach the nature of this sphere that prompts them to change, through dissection and careful analysis. At every point, they will align every such change with a single idea: “How does this relate to my nature? In what way could this change better present and express my nature? To what extent could I better and more fully express my Will in this new place or profession?” Certainly, the Aspirant may have little or even no knowledge of the living nature and inner meaning in relation to which they may place all of this, but still, through reflection and strategy, they will frame this relationship. Above all, they must set an intention—what do they think, how such a change might affect them, and to what degree it could aid in realizing their own star? They must explore every feeling, every doubt, enthusiasm, passion, or blindness of being toward such a change. The Zelator is, above all, a traveler in new lands, yet they always know that no matter how new the terrain is that they enter, it differs very little in essence from all the places they have already been. Each region contains the same laws of the same Universe, and more importantly for the Zelator, the same laws of the human mind. Therefore, the root of happiness may be found in entirely different places, whether on the plateau of Ladakh or within the humble confines of their garage. Their neuroses and inner conflicts will always express themselves the same way, whether with a worldly concubine or with their boss at work. What is needed for the Zelator is simply to observe, to notice, to scan, to assess, and to observe again. For now, the decisions themselves are not important; what matters is the awareness of the process that always springs from within. They must understand that every desire and whim for such changes is, no matter how catastrophic or destructive it may seem for their being, an aspect of their true nature—a path that they have nothing less than the duty to follow. Once suffering is embraced, it becomes the path. And for every living being in all worlds, there is nothing so joyful and exciting as when they hear: “Prepare yourself, we are going on a journey.” Suffering is the frozen, aggregated state of the Will that is unfulfilled and blocked. The moment the Aspirant begins to act, no matter the direction they choose, they will always reach their goal. Is it not said: “If in this hour thou shouldst die, is it not written, ‘Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord’? Yea, Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord!”[1]

Therefore, the Zelator constructs their life and arranges their pawns in such a way that they can finally dedicate themselves to the grand chess game, to the Great Work. In whatever form, in whatever direction, but always and in every way—following their nose. And that is the surest route through the Cosmos. The grade of the Zelator is not reflected in discovering the correct path, but in the courage to set out on the journey without hesitation, relying on the knowledge and tools we have gathered so far. These tools are modest, yet, is not every moment infinitely ideal for the soul’s journey? For the soul has no destination, only the moment of awakening to itself. For it, the question is not of space, but of time. And once this “moment” is realized, the Aspirant will understand that all along, they were in the right place, at the right time.

Another story leads us deeper into the nature of the Zelator’s grade. One of the famous myths of Pan involves the origin of his pan flute, crafted from lengths of hollow reed. Syrinx was a beautiful wood-nymph of Arcadia, daughter of Ladon, the river god. As she was returning from the hunt one day, Pan met her. To escape his persistent advances, the fair nymph ran away and did not stop to hear his compliments. He pursued her from Mount Lycaeum until she reached her sisters, who immediately transformed her into a reed. When the wind blew through the reeds, it produced a plaintive melody. The god, still infatuated, took some of the reeds because he could not tell which one she had become, and cut seven pieces (or, according to some versions, nine), joining them side by side in gradually decreasing lengths, forming the musical instrument bearing the name of his beloved Syrinx. From then on, Pan was rarely seen without it.

The essence of this enchanting tale represents the connection between Pan and the flute—an instrument of Air. The deep significance of wind instruments and their relationship with the Ruach can be found in The Book of the Heart Girt with the Serpent.

“But I heard the lute lively discoursing through the blue still air.”[2]

The lute, a wind instrument, is indeed an instrument of Air. The phrase “lively discoursing” refers to an Adept who possesses the name of their Angel and the living Word of Æon. He resonates with that vibration, his mind attuned and tempered to the frequency of the Universe. This is a clear allusion to the concept of Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel. As he navigates “through the blue still air”, he ascends through the blue spheres of Chesed, ultimately becoming the Adeptus Exemptus. The sound penetrates the Kingdom; the sound symbolizes thought, the lute represents the Mind, and the Air embodies the Soul-Spirit.

According to tradition, Pan’s flute has seven different pipes, which could indeed correspond to the colors of the solar spectrum, indicating the macrocosmic scope of his “influence.” It may also represent the vast expanse and occupation of the Ruach, which “trembles” above Malkuth. Thus, Pan wields the flute as an elevated and brilliant mind, with all its seven-fold attributes—sharpness, wisdom, creativity, contemplation, reflection, curiosity, and perceptiveness. The use of the mind by the Zelator is as necessary as the Neophyte’s understanding of and approach to their body. And just as the body has aspects, limbs, and subtleties, so too the mind possesses various levels, all drawing from the same center, the Self, symbolically represented by Tiphareth as the center of the Ruach. Pan’s flute is an instrument that communicates with the being through the sense of hearing—the sense traditionally attributed to the element of Spirit, the fifth element corresponding to Tiphareth. In this way, the importance of the mind as the true mechanism of the Selfhood is once again emphasized.

The Zelator must remember that it was mania that drove Pan in his pursuit of the charming nymph, and his enormous sexual appetite is what overwhelms her, alluding to the influence of sexual energy on the mental faculties of the Zelator. It would be utterly inappropriate to view this relationship as resembling that of the Neophyte and their Vampire, not in any form or manner. But the Zelator is so subtle and refined in navigating their sexual fantasies for the sake of their place in the Mass of the Holy Ghost; indeed, they now use the power of the mind to channel the terrifying force of sexual energy and begin experimenting openly with sex magic. These experiments will accompany them from this point onward through all grades, where their entire apparatus will be transformed, just as their attitude toward sexuality will be transformed—where the flame of their curiosity will ignite morality, ethics, and all the aspects of their nature that shy away from facing the great Goddess, with their head high, as high as their phalluses.

Pan is clearly recognizable by his intense sexual activity, while the flute represents the calming and channeling of that wild force, which, in its very essence, points to the practical skill of channeling sexual energy. In fact, only the directed Will toward the silent Self enables the proper channeling of that energy. Only surrendering to the Self is sufficient, and only devotion to the great Goddess is allowed. The Zelator begins to gain insight that “every” woman is simply “one” woman, and that every action, every practice, is but one form of one Knowledge and one Conversation, with one Angel—their Angel. The music of the flute accompanies Pan, making him who he is; together, flute and Pan form a peculiar representation of the Sign of Horus and the Sign of Silence—as part of the fiery, true nature with its two aspects. The flute is neither foreign nor limiting for Pan; it is merely the guide through which his energy must travel to find its grounding and manifestation. The focused thought during the sexual act, undistracted by bodily temptation and directed toward the highest, is true magick. We may even dare to say that it is the only “correct” use of sex. The Aspirant must not view the act of Tantra as an excuse for indulgence or exploiting sexual needs, but neither should they view the Mass of the Holy Ghost as an exclusive privilege reserved only for occult or spiritual acts. The Zelator views sexual intercourse as a magical act, but also as true magick in every sexual offering. They must change their thinking equally about both—sex and magick. Only in this way will both become a catalyst for their soul’s growth. There is nothing worse than waiting for the appearance of the Priestess in the Gnostic Mass, as the pinnacle of the ritual, and something solely important and exclusive. Quite the opposite—one must understand the Mass “only” as a reflection of the same magical act that is constantly unfolding in the Universe, which is no different from feeding pigeons in the park or paying daily bills. A Zelator sees in every action the play of Priestess and Priest; indeed, the Mass is the arabesque of the Universe and its caricature; every sentence in the Mass, every participant, is part of an indivisible whole—to which they dedicate their attention as a Practicus in their experiments with Dharana and meditation, but most of all as a Philosophus in the ignition of their devotion and Bhakti Yoga, which is merely the prelude to the grand experiment that awaits them, and nothing more. Only the calm river of thought can soothe the raging ocean of the soul; only dedicated and refined meditation, focused on the Great Work, can frame such a terrifying hive of sexual energy—a force already beginning to stir and attack the Aspirant’s being since the Neophyte’s grade.

The frantic, raw, beautiful nature, in conjunction with a focused, brilliant mind, connects with another important characteristic of Pan: panic. Disturbed in his secluded afternoon naps, Pan’s furious cry inspired panic (panikon deima) in isolated places. After the Titans’ assault on Olympus, Pan took credit for the victory of the gods because he had frightened the attackers. During the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), it is said that Pan favored the Athenians, and thus instilled panic in the hearts of their enemies, the Persians. At first glance, panic appears to be a brutal attack, and its general is neurosis, for it is dressed in the same uniform and rank as they are—that is, unreality and a distorted perception. However, in the case of the Zelator, panic-like behavior can reveal the path that the Zelator consciously and intentionally embarks upon. Their actions may appear to be panic, but in truth, they are learning to enflame themselves in invocation, and in the fire of that dedication, they move their being closer to the Great Work. This approach will never bring complete success, a paradox that the Zelator will experience later, but for now, it remains a valid method in their practice. This specific kindling by prayer, burning in the fire of incantation, is as much Dhyana Yoga as it is Bhakti, and this is essential knowledge for an Aspirant of our Order. Typically, in our youthful minds, the presence of the heart excludes the presence of the head; yet the ultimate truth is strikingly different—this is precisely why our emotional connections are fraught with failure. For where we should go with the head, we proceed only with the head, and where we should move with the heart, we do not move at all. Ultimate success requires both aspects of this spiritual molecule, the brilliant mind and the blazing heart, in equal measure. And so, through the construction of their magical Dagger, the Zelator sharpens their mind to assist the heart in igniting properly in prayer—not through mania or panic, as initially seen in Pan’s manner. This combination is crucial when kindling a fire in desolate and cold regions; a scout carefully selects dry material, then protects the area from the wind, and with a simple, focused friction movement, repeated persistently and patiently, enables the flame to emerge. It is remarkably similar to our work. As the Probationer, their practice repetition resembles the rubbing of flint or twigs; however, the flame is absent, and they spend their existence in darkness and cold. Now, it is the Zelator’s task to discern with their sharp mind which twigs were wet, or if the location was inappropriate because the sheltering wind smothered the flame, or whatever the reason may be. Their job is to investigate the financial report in the company of the Holy Guardian Angel and, like an auditor, to uncover how, under God’s grace, such vast resources are being spent that obstruct the company’s profits. Something is devilishly wrong, and it is the Zelator’s duty to uncover what it is.

The Zelator takes all prior rituals and begins with their comments, changes, and additions, altering the form but always maintaining the thought that it is the same rite, only changing its attire, now preparing for a ceremonial feast, rather than the humble rags once used for meal preparation. In their corrections and alterations, the Zelator creatively produces entirely new things—new rituals and new exercises. They create a new version of themselves. They reassess themselves and their motives, just as they did with their life—changing, often shifting careers, hobbies, and life paths—now they apply the same approach to their inner work. They find in these personal changes the necessary fuel for their ignition, altering the form in parts that are uninteresting to them or do not provide enough internal fuel to ignite the internal engine that will lead them to the stars. The panic-driven, euphoric execution is completely appropriate in this case, serving not as neurosis but as Will. Although both ideas are simply the result and tributaries of a single, great, eternal, primordial river.

The work of the Zelator and the Practicus—both representatives of a specific mechanism of the mind, or Air—always contains aspects of both Bhakti and Dhyana Yoga. In this combination, it brings Vision and Voice, and ultimately Knowledge and Conversation. Always and in every way, always in the combination of “the two.” For in that one moment, the Aspirant and the Angel are forever reflected, as two completely perfect entities—what will be presented and experienced through the accomplishment of the Great Work.

Moreover, the Zelator, like Pan, possesses not only mania and panic but also a strong current of sexual energy and sacred erotism. At this point, it is necessary to elaborate on this very specific kind of sexual drive that adorns Pan. He is famous for his sexual prowess and is often depicted with an erect phallus. Diogenes of Sinope, in jest, recounted a myth where Pan learned masturbation from his father, Hermes, and taught the habit to shepherds. There was a legend that Pan seduced the moon goddess Selene by deceiving her with a sheep’s fleece. Indeed, the manifestations of Pan’s sexuality are numerous and varied, tailored to diverse beings and objects—ultimately, Pan is merely the vessel for his sexuality, which is, in fact, suprasexual—transcendent, an entirely archetypal current that flows through the entire created Universe, compelling both gods and humans to be puppets of this exalted phenomenon, which has accompanied them since the dawn of time. Indeed, the oldest and strangest emotion of humankind is lust, and the oldest and strangest kind of lust is lust for the unknown.

It is of utmost importance that the Zelator does not approach this force personally, nor from any moral or ethical standpoint. In this sacred energy, they must see only and exclusively energy, but not consciousness, character, or any sense of personality. In the same way that direct and alternating currents have completely different applications, the Zelator must view the difference between impulse and willing sexuality. Just as direct current and alternating current have entirely different applications, so must the Zelator observe the distinction between sexuality infused with instinct and sexuality driven by Will.

The Zelator, approaching the Mass of the Holy Ghost, is like a curious boy riding his bicycle for the first time; how much attention, yet at the same time, enjoyment in that exalted moment. The enjoyment is equal to the attention; simultaneously, he learns and enjoys the learning. Their study of the Mass is the application of the Mass; they examine and prepare, preparing their vessel—the body, and above all, their mind for such an exalted, but above all, natural endeavor. For the true partner in this act is the entire Universe; everything else is merely the mimicry and arabesque of that divine act.

Shaking the Aspirant’s morals and ethics deepens their being in a beneficial way, and this is most elegantly realized in symbiosis with their exploration of the sexual act. The Zelator aspires to understand the importance of unrestrained experience, particularly in the realms of sexuality, as a pathway to spiritual enlightenment. They must always go further, more, deeper, extremely, brutally, and provocatively, probing the boundaries of their own nature. All those lavish perversions and hidden sexual desires within must present a testing ground for their brilliant mind, which will bring them to awareness and draw them to the surface, clearly to be seen, allowing them to float and lure dreadful monsters from the unconscious depths to bite them like bait set by the fisher of the Self. Completely free and unburdened to use them when desired, not when compelled. Even as a Neophyte, they realized the influence of the Vampire and its obsessive nature, and now they experience the entire idea much more freely and creatively in life and inner work. Yet, they are still far from complete freedom and immunity from its influence. Certainly, the Zelator does not view erotic implications as inherently virtuous or vicious; they see them as an excellent idea for meditation and a method for scrutinizing their own mind. Let them, therefore, list all their perversions, everything they have experimented with, all their failures and successes in erotic endeavors, their fantasies, but equally their disgusts, and let them create a clear, comprehensive table of them—connecting them with the ideas of the Sephiroth or paths, elemental, zodiacal, or planetary attributes. Then, let them leave them to remain in that table, floating on the horizon of the mind, surrendered to the sun and wind, where they will eventually sink from exhaustion. Let them do nothing with them, for the work and action, as they thought they should be, as they thought they were appropriate, is what kept them afloat on the surface of the mind, instead of resting deep down at the bottom. To that place where all sunken treasures lie, where nothing can be discerned, and where no value can exist—where both gold and mud hold the same value, which is one single currency: oblivion.

There is another strike and shaking upon the shoulders of the Zelator, which they must view in a completely different light than they might initially perceive, if they blindly follow the prescribed program. The Zelator is tasked with studying and memorizing a chapter from the Book of the Law. However, it is essential that the Zelator openly approach the idea of accepting the current Æon. In fact, by being incarnated in this time, they affirm the sequence of events and circumstances that demonstrate their readiness to align with the Æon of Horus. Furthermore, they must resist the temptation to declare the Æon of the Crowned and Conquering Child as the New Æon. The Dawn of the Æon will never experience its afternoon as long as we label it as New, rather than Current, or, most appropriately—Ours. The crucial question is Horus’ role in our Æon, whether we recognize and accept his place on the throne from the heart, or accept it by force, like an election night where the winning candidate fails to inspire our affection. Do we accept the Law because we desire it, because we must, because someone we deem worthy embraces it, or simply because there is nothing else on the menu?

In the same way as in the Liber Pyramidos, which involves two participants—the Probationer who begins, and the Neophyte who completes—the story from the beginning also includes two aspects of the divided Aspirant: Semele and Dionysus. One Aspirant reads the Book of the Law and strives to memorize the chapter, but by doing so, at one point, he transforms into a completely different Aspirant, one who just accepts the Law as it is, and embraces it by his own Will—not through memorizing the chapter. He will not recite a song like a child in kindergarten; rather, he will tell his Superior what the Law is. He will be nothing but the Crowned and Conquering Child, who does not recite the law but commands the law.

Frater 273

You might also enjoy:

- The Neophyte – The Neophyte grade viewed through its inner psychological processes and its deeper symbolic meaning.

- About the nature of Genius – What “Genius” means in the Thelemic A∴A∴ context.

- Persephone – Mythic symbolism tied to cyclical spiritual truths.

- On Pentacle – A study of the Pentacle as a microcosmic representation of the universe and a tool in magical work.

- Enochian Mercury Senior of Water tablet – Exploration of an Enochian water tablet and its inner implications.

[1] LIBER HHH sub figurâ CCCXLI, section SSS, III:12.

[2] LIBER LXV, Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente, II:32.