The principles examined within the practice of Asana naturally extend to Pranayama as well. The fundamental objective is to foster complete awareness in every action, including those that originate from the unconscious mind.

Pranayama is the control of Prana, but it is essential to first define what this concept truly means—otherwise, any discussion remains mere speculation. Prana is what may be called force, but not like fuel, rather as nourishment for the spirit. It has many aspects and, what is called, Rupas, so it can be found in food as in blood, but neither food nor blood is Prana. An abstract idea enshrines Prana, and it is necessary to utilize a specific model of thinking in order to understand its true nature. Prana is the prime representative of the magical link. Ingenious Aspirants can see Prana in each thing and pour Prana into any object.

However, Prana is usually associated with a common living factor for all things alive. It is not blood, though it can be, because blood is limited by its color, warmth, and confinement in blood vessels, but the magical link par excellence is the breath. Therefore, Pranayama is breath control, full awareness of the entire apparatus, which is used for breathing. The breath is continuously inhaled, to an extent at which is exhaled. Its field of action is within, as much as without. Life breathes in, death breaths out. Everything inhales, nothing exhales. That one sequence is everything about all, and all about everything, the whole Universe, visible and invisible, are just modifications of that single sequence–the sequence of one inhale and one exhale.

As in the explanation of Asana, control is also essential for Pranayama, but with burdened attention and automatic awareness, which we will achieve with statics. With Asana, it is easier, while with Pranayama, it is impossible, as long as there is a biological tendency to breathe, and thus to move. What applies here is static tempo, not the structure. The inhalation pace must be balanced until the attention diminishes, and control and a stable rhythm turn into automatic consciousness. Therefore, awareness should be focused on the uniformity of the pace of breathing.

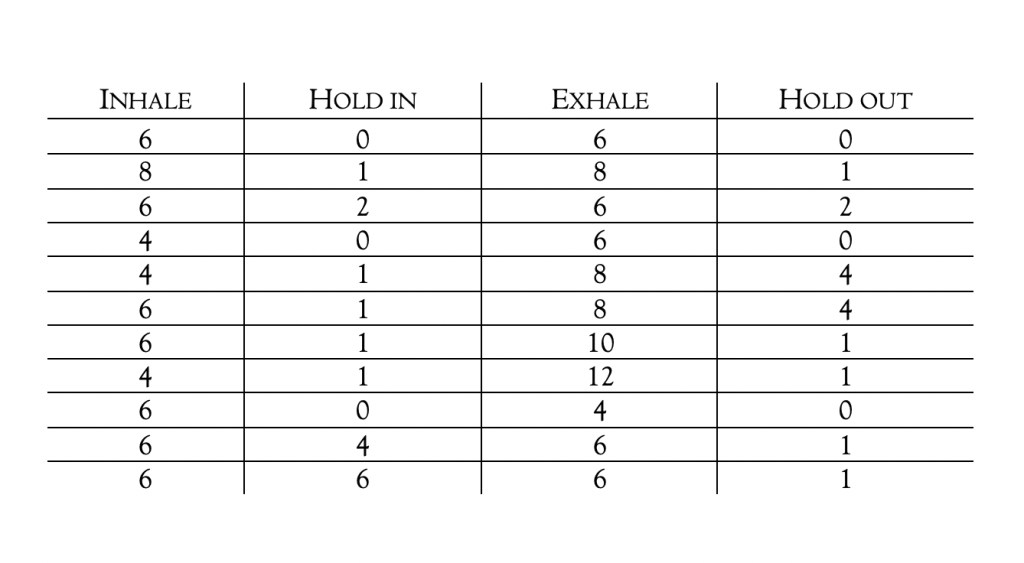

Let us therefore consider all the variations, paying close attention to the details. However, here, I absolutely do not want, even for a moment, to waste time debating the rhythm of Pranayama—whether you will apply 4+4, or 8+8, whether you will perhaps use 4+2+4+2 (inhale+pause+exhale+pause), or even 4+8+7 (inhale+exhale+pause). This is something that is simply understood—each Zelator must begin experimenting and exploring the rhythm and pace of breathing, and with their diligent records, become the helmsman of this restless ship. What I aim to instill in you, however, is the thought of a wondrous land far beyond the shore. As the captain of this ship, I wish to implant within you a manic vision of paradise-like lands, so wild and enchanted that no one else would dare follow you there. The fascination with details that are not at all entertaining leads to Pranayama in our program being experienced as grammar or algebra by young souls. But we must completely shift our perspective on the whole matter, and not only that—we must change the very angle from which our practice arises, our living experiment, one which I intend to bring you so many new, vivid experiences, those that will drive you to search further, all the way to that promised, magical land.

There are a few experiments with Pranayama that I want you to perform. Rapid breathing can quickly and sharply introduce energy, but unfortunately, that energy is often discarded as a trauma of hyperventilation. When we breathe rapidly, forcefully, and shallowly, it leads to an increased expulsion of carbon dioxide from the body. Since carbon dioxide is acidic, reducing its concentration in the blood raises the pH value, making the blood more alkaline—this state is known as respiratory alkalosis, which often results in body spasms; fingers and palms of the hands and feet cramp to the point of physical pain, and our bodies quickly begin to feel stiff and lifeless, like a corpse.

However, if we continue further, we will notice that our inner state of being is shaken in the same way. Euphoria arises, the body becomes strangely inclined to curl into a fetal position, and through our minds, the earliest memories, feelings, and childhood experiences rush by, which we pass through vividly and turbulently. It is important that the Aspirant continues breathing in this manner and at the same pace, and most importantly, without pauses between the inhalation and exhalation. The inhale must be active, conscious, and even aggressive, while the exhale must be completely passive, letting everything fall, sink, without any conscious muscle tension. The inhale is brought in with full force, full attention, and active intent, while the exhale happens effortlessly, with pure mechanics of the lungs emptying themselves. Breathing is done through the mouth, strongly, energetically, and quickly. Wherever there is any cramping, and it is usually the fingers, then the palms, elbows, thighs, and especially the area around the mouth and nose, wherever this fantastic cramping and tingling appears, filled with energetic needles and life electricity, it is important to keep breathing, and with active consciousness, pass through and move beyond this place, not avoiding the blockage but confronting it with conscious attention. Fear often emerges at this stage—just like the paralysis we experience in lucid dreaming experiments—but there is no other instruction than “keep walking, Johnny.” A word must be said about this primal fear that arises; for some, it will be an open fear of death and dying, for others, it will be a regression and a shudder at something demonic that haunted them in childhood, and for yet another, it will be the fear of something that will happen, something that will be inserted into their mind as a fixed idea, completely overwhelming them and veering them off course from the very simple instructions: active inhale, passive and relaxing exhale, no pause between inhale and exhale, quickly, energetically, consciously, and vividly—only this, and nothing more.

There are no words that can describe the atmosphere of consciousness you enter, even after twenty minutes. For describing this state, I will not waste words except—dare to try it. Our entire being will dwell in a space filled with energy, very strong, very alert, made of the same substance as our consciousness. It is of crucial importance that no pauses are made between the inhale and exhale, but this is far from simple, for the euphoria and the change in consciousness that will undoubtedly follow as a result of the accumulated large energy will cloud our mind. It may happen that we are in pure ecstasy, and minutes may pass before we notice, by accident, that we have been holding our lungs empty the entire time, without any impulse to inhale. The Aspirant must keep their attention on the inhale, fast, strong, and active, above all present—that is all they must do, that is their only beacon that will guide their boat through this unearthly storm.

The effect of this kind of breathing is exceptional, not only for the physical but also for the mental apparatus of the Aspirant. The consequences are so varied that it is impossible to write any observations or rules about them, as each Aspirant has their own inner mechanism that both unlocks and creates a lock, according to their unique key. The conclusion is simple—the Aspirant must explore and turn everything further into personal insight, carefully recorded in the magical Diary. We have opened this great and vital chapter on Pranayama with a practice not found in the classical curriculum—strong, shallow, and rapid breathing—for the simple reason that it offers the Aspirant the most immediate and powerful firsthand experience of Prana.

Indeed, the sensation is so distinct that this radiant energy takes on a specific taste, scent, and texture of awareness within the body—until the body itself becomes saturated with its unmistakable presence. This method serves as the most effective means to identify and imprint the nature of Prana in the mind. Later, even the mere recollection of its unique character will be enough to summon the necessary inner conditions for success. To master any force, one must first feel it directly—experience its essence, perceive its nature. While this rapid breathing is a powerful tool for swift energy accumulation, its deepest value lies in offering a direct, unmistakable encounter with Prana—that fine vibration, and energetic tremor of all our living cells and tissues.

Deep breathing is our next station, and it is something for which it is hard to believe that there are not enough detailed reports. It is a simple fact: even when you inhale deeply, there will still be room for more air. It is as if we have been taught never to fill that space with air, as if we had an automatic mechanism that gives us a comfortable feeling when our lungs are full, even though there might be room for more air. This is an excellent point to invest our astonishment in the lack of instructions that would adequately describe the correct way to inhale air. Usually, Pranayama instructions are limited to just two parts—the initial one, where we inhale into the stomach, filling the belly with air, and the final one, where the diaphragm rises, filling the remaining upper part of the lungs. However, too often, the third segment is neglected because now, the diaphragm and the air filling the upper part of the lungs leave a vacuum in the abdominal area, even slightly drawing inward. Therefore, let us proceed with the details.

First and foremost, it is assumed that the Aspirant has already mastered at least one Asana, regardless of how simple or physically undemanding their chosen posture may appear. They must have passed through all stages of Asana—achieving complete stillness, the rigidity and presence of a stone statue, dissolving all awareness of bodily position and form. Most importantly, they should have cultivated a distinct inner sensation: as if suspended from above, hooked directly through the crown of the head, with the gathered hair fixed firmly in place—anchored at the Sahasrara Chakra.

Once the Aspirant has grounded themselves in Asana, they must first learn to exhale before officially beginning the Pranayama practice. The exhalation must be performed consciously, without aggression, and it must always be part of a seamless whole, flowing without interruptions or tension. The air is first released from the lower, abdominal part, and then from the upper part, which gently lowers the shoulders. In this way, the Aspirant will gain an unmistakable sensation that the lungs are truly empty, in the same way that the three-part inhalation brought the feeling of the lungs being completely and maximally full. However, in every regard, the Aspirant must constantly remind themselves that the lungs are always filled with the Self, with or without air. Even empty lungs are filled with the thought of “emptiness,” which is the pure potential of full Will. Their thought is what is in those lungs, which are themselves thought and nothing more, both toys of the Self with which it plays with its attention. The thought of inhalation brings the thought into the lungs, not the air. This is such an important idea that the Practicus and Philosophus will later deepen in their further work on Yoga.

The Aspirant must not rush the process of emptying the lungs, nor force anything, even slightly; nor should they do it forcibly, but rather relaxed and easily, allowing the act of exhalation to release all their life-giving processes out of themselves. This is such an important moment in the Aspirant’s entire life, an observation related to breathing in general, not just to the idea of Pranayama: learning to exhale with a sigh is not physical emptying, but an action of consciousness, in which we turn to passivity with attention. That sigh, which is only formally an exhalation, represents active passivity, conscious unconsciousness, so to speak, by which we relinquish but do not neglect the processes within us. It leads the force of a frantic river into a pastoral canal, but without allowing such passivity to stop the water and turn it into a foul swamp. Such a sigh has nothing to do with the lamented, sorrowful movement of regret and doubt, but rather with the release of vitality, courage, acceptance, and confrontation.

It is of essential importance for the Zelator to learn to exhale with a sigh, not merely with an exhalation, and to learn within it to release all that was achieved and made conscious with the inhalation. Inhalation and sigh are two extremes, two directions around which the axis of the Self turns. Wherever the Self is, there the sigh arises; the exhalation, on the other hand, is a completely shallow category that the practitioner of Yoga detests. It is a necessity and inevitability of animal instinct. By the very fact that the air is inhaled with active consciousness, that used vitality now has only two ways to leave the lungs: through conscious sighing or automatic exhalation. Only the sigh releases the used and recycled inhalation, only the sigh is worthy of the attention that brought life to the Self, not to the lungs. One could say that the intake and sigh are the fine, noble manners of the Self, while the inhalation and exhalation are the tics of a boor and a brute. Indeed, the Zelator must learn to exhale with a sigh. His breathing transforms into the graceful strokes of fins, allowing him to navigate the endless ocean of vitality, rather than the frantic thrashing of a fish in a dried-up lake, where its fate is sealed and sorrowful.

Inhalation and exhalation do not last in seconds, but rather they last as long as it takes for a moment of the Self to pass, which does not at all depend on or indicate a physical second. This is the basic and smallest unit of our vitality and the amplitudes of the pendulum of the Self, and it is the only way to present inhalation-exhalation in a manner worthy of our teaching.

Now that we have established such vibrant, authentic reflections on something seemingly as simple as inhalation and exhalation, an extremely important element follows, and that is the correct approach to Kumbhaka—retention of the breath where there is no inhalation or exhalation, where breathing ceases through Will, and during which the Aspirant’s lungs are frozen in time, but not in consciousness, which always maintains the same uninterrupted, continuous flow. This is such an important observation because beginners often perceive this pause as mental passivity based on waiting and simply counting seconds. This pause is anything but passive; it is, in fact, the pinnacle of this divine region, where pure Will resides, the Self in its natural habitat. The habitat of possibility and potential. In the moment of Kumbhaka, or the pause, Will must be like a taut arrow, which, although it appears calm externally, owes its precision to that very calmness. But as calm as the force waiting to be released is, so powerful and penetrating will the release and surge be. The arrow does not wait to be shot; it is ready, it anticipates but does not wait.

The pause in breathing is an active anticipation, never focus; it is the very anticipation that is so crucial to the attainment of the Holy Guardian Angel. During this pause, Will is neither directed nor intensified—it simply remains with itself, precisely as it is, shaping the entire Universe in its assistance of its manifestation. The whole mechanism is neither causal nor consequential, but rather alive and nested in the moment. The moment of inhalation and exhalation is what grants them the characteristics and perception that it is inhalation or exhalation when one emerges from that pause. When the Aspirant practices 4+2+4+2 breathing, they inhale for four seconds, then pause for two, then exhale for four seconds, and pause for another two seconds, after which the whole cycle repeats. It is precisely in that word “repeats” that the greatest enemy of Yoga is established–it is about repeating the form, but not the moment. The moment is singular, just as vitality is one, uninterrupted, always the same. Breathing cycles are just an illusion of the whole being, which does not repeat. Only the impression of that action repeats, which the Ego “repeats” due to its inability to comprehend it as “one.” It cannot grasp breathing as a concept; instead, it creates the idea of inhalation and exhalation, dividing the concept into segments. During meditation, it is far more comprehensible and easier for the mind to say to itself: “inhale,” then “exhale,” rather than “breathe, breathe, breathe.” Try this seemingly trivial yet deeply beneficial exercise: sit in your Asana, and after a few minutes of stillness, begin softly saying “inhale” as you inhale, and “exhale” as you exhale. Continue this for a while, at a completely relaxed and slow pace. After a few minutes, change the phrase and now say to yourself “breathe” at any point during the breathing process, whether it is inhalation, exhalation, or the pause. Simply say “breathe” to yourself, without relying on inhalation or exhalation at all, completely liberated from the movement of the lungs, entirely outside of any rhythm. Say “breathe” however you wish, whether slowly or quickly, with longer or shorter pauses. Say it when you feel like it and when you sense it is needed, not when physical breathing or lung movement demands it. You will feel a drastic difference in awareness compared to the first repetition, which consists of “inhale” and “exhale.” In this way, it will feel as if your being is emerging from the shell of bodily lungs; there will be a tone that sounds as if the whole Universe is playing it. You will get the impression that the lungs are moving, but no air is entering them at all; instead, it is everywhere around us in the same way, as if this mimicry were like a pantomime of the spirit, whose primary task is to entertain us, not condition us for life. This is truly an interesting exercise that does not require much time, but it beautifully explains everything I initially wanted to convey regarding inhalation, exhalation, the pause, breathing and breath, as well as the mental attitude within us that defines these concepts.

It is a spin of the spirit, which radiates with the same force throughout, yet it turns, and from the perspective of the observer, it seemingly sends the illusion of a pause or activity, inhalation or exhalation, even though it is active the whole time, or passive, depending solely on the position of the observer. This particle of the Selfhood neither inhales nor exhales; it always breathes in the same way. We are the ones who, through our observation, define this action as either an inhale or an exhale, depending on our position and our need. This spin is at once both the one who inhales and the one who exhales; it is both the one who Knows and the one who Converses–the one who performs the Abramelin operation and the one who is summoned by it. All that can be said of every grade preceding this sacred operation, the only one truly worthy of being called an “act” in the fullest sense, is that they are merely preparations, warm-ups for such a sublime undertaking. They are spins, just like inhalation and exhalation, existing simultaneously as both achievement and performance, as both success and failure. From the standpoint of the Selfhood, every grade is at once accomplished and unaccomplished.

Try the following, a very fitting exercise, which can lead you into the folds of Samadhi if you are not careful enough. I want you to simply inhale and exhale, without any counting or keeping track of the time of inhalation and exhalation. But I want you to make no pause in between, meaning breathe without interruption, that is, Kumbhaka; inhale then exhale, inhale then exhale. But while you are inhaling, I want you to concentrate on the Universe that exhales that very same air. As much as you inhale, the Universe itself is exhaling that same breath into you. Do not focus on the Universe, but rather on the feeling you experience as some other lungs empty while you inhale, and vice versa, which are “outside” of you. Very quickly, your being will fall into a special type of trance, in which every inhale is simultaneously an exhale, and every exhale is simultaneously an inhale. At some point, you will enter into a strange state of equilibrium, where “inhale-exhale” will no longer be a state but mere subjective epithets, performed in the same way always and in every way. There will not be a single part of the inhale that will not equally be part of the exhale. Suddenly, you will get the impression of lungs that are merely physically moving, while the air flows continuously inside and between them, constantly and unceasingly.

This is an excellent point to mention Mahasatipatthana, in the same way we addressed the matter of Asana; we do not perform the inhale, but rather “these” lungs inhale, just as some other exhale. Through further practice of the exercise, you will loosen “this” to such an extent that all the lungs of all worlds will be equally just a consequence of the Will to breathe, just as the tongue is only the embodiment and birth of the Will to speak, and nothing more.

Truly, undertake such a sublime act and observe your being during the breath retention, carefully watching how you stop the inhale, how you prepare for the moment before the pause, as well as the moment before you intend to begin the next inhale. You will see very subtle and fine tremors in the pulmonary apparatus, even more so mentally, like delicate moments of weakness. How much insight into our nature is hidden in these few moments; these tiny fractions of time during the completion of the inhale, but mostly during the pause, represent the best psychoanalysis and psychotherapy we can receive from the Universe, unfortunately so rarely utilized.

There is a very interesting observation about the beginning and end of the pause in breathing. As you follow the inhale or exhale with attention, and as the cessation of the inhale or exhale approaches, you will notice a temporal vacuum appearing at the very end of the inhale or exhale, which simultaneously marks the start of the pause. This moment, which is neither breathing nor a pause in breathing, is a moment of Pure Will, in which we have no need to breathe, only pure existence. In that moment, there is no need for inhalation because the inhale is still “continuing” in that specific neither-nor moment, but there is no need for a pause in breathing either, as it is simultaneously already paused. Pay close attention to find that instant, that moment which is not part of time but of consciousness. Try to pinpoint the exact time when the inhale ends and the pause begins. You will be surprised how brief that moment is, eternally shorter than a second, wide, diffuse, and vast. Then, turn your attention to the exhale. I want you to exhale slowly, completely relaxed and surrendered, without blocking or holding your breath. When you reach the very end of the exhale, I want you to freeze the moment when it finally stops. You will see that the mind continues to “exhale” even when the lungs have finally stopped. This movement is also brief, like the previous one, eternally shorter than a second, but clear enough for you to notice. In the same way, you will see that the same momentum is present a moment after we completely inhale and stop the lungs at the peak of that inhale. Like in a weightless state of strange inertia, the mind will continue performing the mental action of inhalation, even though physical inhalation is no longer occurring. All these moments are exquisite traces of Pure Will, which breathes without lungs, which thinks without thoughts. Dedicate yourself to exploring this process; you will be astonished by how many wonders are hidden in seemingly insignificant and unnoticed moments of Pranayama, moments to which few books are gentle enough to give a place on the page.

Kumbhaka, the moment of pause when the lungs are motionless, as you will come to notice, is actually outside the category of time. Whenever Kumbhaka occurs, it is never merely a pause in breath, it will always be a fraction of awareness that exists beyond the concept of time, beyond the counting and ticking of seconds. This is precisely why it is there for the Aspirant, who in Yoga always and everywhere sees the path to enlightenment and Samadhi, which is the only and exclusive goal of its entire execution. It is very important for the Aspirant to get used to thinking about all elements of Yoga in a self-reliant, authentic, living, and, above all, interesting way. Even in completely mundane things like Asana, they must stretch their spirit so much that they are not even slightly in the body that sits. In Pranayama, they must breathe with everything, except the lungs. In Samadhi, they must be everything but “the one” who is only trying to achieve something as meaningless as enlightenment.

In his letter to York, 1945, Crowley writes:

“I cannot agree that Asana and Pranayama are exclusively Hatha Yoga studies. The point surely lies in the motive. I have never wanted anything but spiritual enlightenment; and, if power, then only the power to confer a similar enlightenment on mankind at large. I think you are wrong about my history. I did practically no Yoga of any kind after my return from my first journey to India. I attempted to resume practices at Boleskine and elsewhere, and could not force myself to do them. The Samadhi is a sort of by-product of the operation of Abramelin.”

Indeed, let the Zelator dedicate all the time of their grade for the anatomy of Kumbhaka–this sacred moment of breath retention, or when our lungs are emptied, often held by the muscles, becoming blocked and neurotic, while externally one may think we are in perfect peace. Do we inhale completely, or is there still room to take in more air? Do we hold any remaining air when we exhale? When is the pause longer, after the inhale or after the exhale? It is crucial to consider all the positions of such behaviors and habits, as they can be decisive in achieving Yoga. This is the ideal field that first teaches us that the true realization of Yoga is meant for children and their innocent curiosity, not for the study of a serious and professional know-it-all bibliophile, but for the inquisitive, inexperienced, and euphoric child who sees in it not a test, but a toy. A child who sees in this a prism for the highest light, which breaks into colors, painting their Will in the crayon box of the Universe, pushing their euphoria—always towards that colorless light, which imperceptibly, yet persistently, contains all those colors, and all experiences, all Yogas. All limbs of Yoga are always and only one Yoga. Kundalini Yoga is the same Yoga as Hatha or Mantra; as long as our ultimate goal is simplicity, and not unity, we can hope for success.

No matter the tempo chosen, or the form, whether with or without Kumbhaka, the breathing cycle must in no way show even a slight hint of interruption, nor any abruptness in the transition from inhale to exhale or vice versa. In fact, it is all one wide, integrated movement. The transfer of air from the abdominal, lower part to the upper part, as well as the subsequent re-filling of the lower part, must be imperceptible, like a magician performing a trick with their right hand, making your mind forget what is happening with the left. It is one wave, one movement, whose peaks and troughs only appear distinct to the untrained eye. Our Student must always keep in mind the idea of a wave, never of amplitude. The diaphragm and upper part of the lungs should automatically engage when the air spontaneously begins to transfer to that part. Such flow must be subtle and spontaneous, never by intention or, God forbid, by effort. Certainly, practice will show the Aspirant how and to what extent this should be done, taking into account that simply reading these words has left an imprint on their mind, which is enough for everything to fall into place once they begin to practice.

The crown of this practice is to accept the premise that breathing reflects the inner state, but also, conversely, that the external state can be conditioned by the breath. However, this does not mean that the point is to change the state that expresses our nature through breathing, but to consciously pass through each stage of the inhale–whether shallow or deep, and most importantly, to discover why it is shallow, why we are breathing rapidly or blocked, and to dwell in that state openly and ready to experience it as it is. As much as sea waves are fantastic, we do not enjoy the waves, but the sea; the waves are merely an expression of the nature of the sea. Whether they are turbulent or calm, that sea is always the same sea, and even the fiercest storm, by the next day, is completely distant and a faint memory when the sun breaks through the clouds, opening a beautiful, calm horizon on the same sea.

There is one more thing regarding deep breathing that we mentioned at the beginning of our discussion, which has so subtly eluded our minds. While we were talking about many deeper and more complex matters, we forgot something much simpler, hidden right before our eyes all this time: what I want to draw your attention to is a very simple fact–that when your lungs are filled with air to the maximum, there is always a certain amount of air that can be inhaled, but our mind simply does not perceive it as a resource. In other words, when you feel that your lungs are full, they are far from it. There is another hidden, shy breath “behind,” like a reserve kept by our unconscious nature, which is never used, thus remaining deprived of a part of itself, a part of its wholeness.

This type of breathing should not be performed according to a rhythm or by counting, but solely with awareness of the depth of the inhale, which should be done in the three-part method we learned earlier: first with the abdomen, then the upper chest, and finally again with the abdomen. And it is precisely when we reach the very end of this process, when the lungs, ribs, and our entire living apparatus expand, when we come to the physical limit, that we should pause for a few moments, feeling now the entirety of our being, which is full of air and living energy, with a living will to breathe above all. And then we should make an effort to inhale even more air. We will be surprised at how much easier this additional intake of air is when we pause during the inhale, rather than immediately trying to force that same amount into the previous volume. Our thoughts may be limited by fear; we might worry about breaking or fracturing ribs, and all sorts of things might cross the mind of the Aspirant, but their only goal should be to inhale more air at any cost, even if it means the lungs will break. Finally, we expel all the air, but always in a relaxed manner, without pushing, letting the air leave the lungs on its own, without any forcing, blocking, or resistance.

We repeat the entire process, inhaling and filling the lungs to the fullest, then making a very small pause of a few seconds while holding the breath, and finally inhaling just a little more air beyond that limit. What will happen as this exercise is repeated day after day, progressively increasing both the flexibility of the lungs and the flexibility of the mind, which is taking in more and more air, is something worth paying closer attention to. This simple exercise is incredibly beneficial for our psycho-physical apparatus, as the body performs a very special act of stretching, bringing life to parts of our being that have never been accustomed to being used, and now they seem to return this favor with gratitude. We reach a strange period when we have accustomed our being to taking in this hidden potential of our lungs, chest, and diaphragm—the body starts to manifest a subtle, barely noticeable feeling, similar to an orgasm, something like a mixture of yawning and orgasm, on a much more subtle level. The Aspirant will experience sudden bursts of very fine energy, completely spontaneously, throughout the day. They are like tiny bursts of bliss, spreading through the Aspirant, bringing a pleasant sensation. The appearance of these waves is always accompanied by a specific feeling of happiness and joy, which often manifests as smiles on the Aspirant’s face. As we practice this type of breathing day after day, even physical orgasms will become longer and significantly more intense, and the feeling of that specific miniature orgasm will somehow attach itself to the very peak of the inhale, every time we apply that extra inhale, as described earlier, as though it had been waiting for that last ounce of air for years and now, freed, it releases that fantastic energy which we feel in all the peripheral cells of our body. Primarily in the fingers and toes, and often in the tip of the nose and the back of the neck. That blissful feeling of arousal is like the sensation when we imagine someone scratching a school chalkboard with their fingers, causing a completely authentic shiver in us. Simply put, this is a similar feeling, but far more pleasant and beautiful. Throughout the day, the Aspirant may experience spontaneous outbursts of inner euphoria and enthusiasm. They will often feel an urge to jump, run, or shout; our wholeness, for the first time, breaks out of its confined state, returning to us in a measure that strikes like tectonic blows to the Selfhood, throughout the day. Even now, after so many years of practicing this breathing, it is enough for me to simply think of such an inhale, which expands the chest beyond its limits and adds “just one, only one more inch of air,” without even physically performing it–and the same type of energy immediately flows through my being. In a way, physical movement and inhalation are not the only conditions that awaken this energy, but rather, it is the thought, attitude, and readiness to take “more.” More air, more vitality, more life. More, wider, deeper. It is as if that movement is like a playful child mimicking adults—even when we are angry at them, their mimicry of our movements immediately makes us laugh and forgive everything they did just moments before. It is the same with this movement; we do it while our whole Soul-Body being responds with its smile, bringing that specific energy into our nervous system, healing us. Tingling on the surface of the skin is also a side effect, and sometimes it may seem that we have a slight rise in temperature. To a large extent, this feeling is purely subjective, but it is not uncommon for a rise in temperature to actually happen on a physical level. The Aspirant should record all these phenomena in their Diary and define their own pattern for how this euphoria manifests. Of course, such a pattern does not exist, nor can it exist, but this attempt to frame something as fantastic as this energy serves additionally as a kind of foreplay in the act of unity with our Soul-Body. This simple exercise is immensely beneficial for our psycho-physical apparatus, as the body performs a very special act of stretching; that surplus air is actually not a surplus–we are actually learning the true measure of breathing, and now our being, like an euphoric child on the way to a birthday party, expresses its true nature, not a new one. We are not taking excess air, we are simply learning to breathe without a shortage, as we have done up until now.

But let us now observe the exhale; it is also under question. For the exhale to be complete, the diaphragm must be relaxed, and the muscles must not restrict the lungs from fully emptying. It seems that the main muscle driving the entire breathing process is, in fact, our neurosis. Let us observe the Kumbhaka; I know we have already covered this, but I will repeat it once more, two more times, and even more-let us observe ourselves when we exhale, what we do, and how the lungs are actually contracted, unprepared to take in new life, stumbling in their present, momentary aliveness, like mischievous boys intruding into a girl’s hopscotch game, trying to tear everything apart, only to trip themselves and fall into the same hopscotch. During the pause in breathing that follows the exhale, notice how our abdominal muscles tense, and the sensation of the body takes on a subtly awkward, distorted position, like when we are performing a bodily function. Everything mentioned here is, of course, on the level of micro-movements, unconscious positions to which we must direct our attention in order to realize how everything stands on crooked feet. We think about breathing, and by thinking about it in the correct way, we will start breathing more correctly. We will notice that, no matter how much we believe our lungs are empty, there is always more air, just as when we focus on a deep inhale, thinking we have filled our lungs completely, we realize they still have room for more breath.

The repose of the exhale holds so many fantastic resources for inner work, which can be incorporated into our everyday practice. Let us do a wonderful exercise that involves the exhale in such a lovely way. Stand at the center of your circle, intending to perform your Pentagram ritual, but this time with one modification. The entire ritual must be completed in one single exhale. The entire Qabalistic cross, all Pentagrams and Archangels, all movements and vibrations must fit into this single exhale. This will make us exhale as long as possible, but the actions must also be performed quickly, while the vibrations must merge into a single sound, with numerous rapid changes of syllables. When performed, the Aspirant executes the entire ritual in one exhale, mumbling a single word that constantly changes, moving the mouth just enough for the mind to become aware of which vibration is being activated. The Aspirant must not concern themselves with form, but must remain relaxed, informal. This must be more of a free improvisation, like an artistic sketch, an incidental pattern or a glimpse of the ritual, which elevates the Aspirant more than the ritual itself, which is closed, expected, and shaped by repetitive conventions. This change will shock the Aspirant’s mind, which will be amazed by the efficiency of this execution; on one hand, by speeding up the movements, the Aspirant will seem to be on a fast track, which will affect their subjective acceleration of time. On the other hand, the slow exhale that brings the effect of compressing time will create a fantastic combination, one that simultaneously raises and lowers the sails of the ship on which the Aspirant’s awareness is navigating. When the Aspirant performs this, simply sitting in their chair, mumbling without opening the mouth at all, with one exhale they can perform the entire Liber Samekh, imagining it all in their mind, soaring beyond the form of the entire ritual, leaping through mental jumps, like Pan’s wild goat, flying far beyond logical and rational barriers that, in the entire concept of freedom, they had imprisoned and framed themselves in. There, far beyond the circle, beyond the reach of our expectations and understanding, lies our true ritual, our true performance. The ritual is merely a slight aphrodisiac and nothing more, for something that must follow without preparation, without learning or rehearsal. The true Mage acts immediately and without preparation; their true ritual is completed the moment they physically begin to perform it. Its realization is in the mind and the Will. In the circle, only the effect of thunder after the lightning happens, for something that has already been accomplished long before it was perceived and noticed by the limited mental apparatus. True LVX strikes the being with its flash before the ears can hear it, and before fear appears as a side effect of the Ego to the appearance of the light of illumination-because the Ego will never be able to reach that light by performing rituals, or by any technique or practice. That is why it fears every time it hears thunder, because it does not see the light somewhere far off, like the lightning that split the sky, because it keeps its eyes shut, frightened like a child, not understanding the nature of the Great Work, refusing to free itself in the execution of the ritual, finally realizing that there is nothing in the ritual that would lead it to the goal. This fantastic exercise can bring about a change in the routine and dull performance, so that the entire ceremonial magic in the life of an Aspirant begins to radiate a completely different light. Let the Aspirant perform the same approach with the Middle Pillar, or any other ritual or practice, and feel the exhilaration of their spirit, leaping from the impact of such a simple yet effective shift. This subtle change, born from the idea of completing an entire ritual in the span of a single exhale, will ignite a surge of energy, as if the very essence of the practice has been distilled into that one, unobtrusive moment. Let them fly across the vibrations, the signs, skipping some of them, skipping even whole sides of the world and the recitation of certain parts of the ritual, while holding in their mind only one single thing–the end of the ritual, not even the last word, but the period after that word, which resides in silence. Toward this, they must desperately chase, until all the air in their lungs is gone. Let them do whatever is within their power for this, even if they make mistakes and exclude entire stanzas and vibrations, while their lungs brutally empty, but let them only sing toward that primal ritual, under the threat of their life. This invention and method of performing the ritual during the span of a single exhale is not so much tied to Pranayama, but to the idea of changing our entire approach to the matter. But let the Aspirant freely, boldly, and independently explore other ideas, let them come up with their own variations, which will make their lungs breathe life itself, not just air.

Next, I will introduce another fantastic exercise that is so different from the usual 4+2+4+2 and similar forms, and it is very difficult to find many details about it. It involves performing shallow, almost nonexistent breaths, so subtle that there is no pause in between them. To an observer watching the entire process, they would not notice any movement of the lungs or stomach; it would appear as though the Aspirant is completely still and not breathing. Before attempting this, it is beneficial for the Aspirant to perform several cycles of relaxed, slow breathing, with a tempo of 4+8, or even 8+16, without Kumbhaka. This introduction should mentally prepare the Aspirant for shallow breathing, or better said, shallow tremors of the lungs, which require calmness and total relaxation. Even a slight emotional blockage or tension makes it nearly impossible to perform this exercise. First, the breathing is done with a larger amplitude—breathing continuously without Kumbhaka—and then the lung movement gradually decreases until it is almost imperceptible. This creates a truly fantastic circumstance where the Aspirant will discover that, at one point, when they completely reduce the amplitude of the inhalation and exhalation, they only need to think about the breath for it to be drawn in, filling the lungs with just enough air to sustain them. It is as if thinking about breathing itself causes the breath to happen. They will realize that they are breathing with their mind, not with their lungs. The Aspirant should try to understand themselves as a thief, so cleverly stealing air in an attempt to avoid detection in the dark. It is like children who, when afraid of the dark, hold their breath in fear that the monster lurking in the dark will notice and hear them. With such shallow breathing, their mental activity will similarly reduce in amplitude, and the Aspirant will attain a completely strange, unique consciousness. Their awareness will follow a smooth, perfectly even line, with the breath following its course. This will no longer be a wave, with its active and passive phases of inhalation and exhalation, but rather a fine, barely noticeable pulsation, which exists entirely undetermined in time and space and can persist indefinitely. Such breathing will lead to an interesting set of physiological and psychological reactions. The first change will be observed on the surface of the skin, manifesting as a tingling sensation and a subtle, almost imperceptible feeling of current or electricity.

It is quite expected that many Aspirants would consider the appearance of siddhis—mystical powers and abilities, often mentioned in Yogis’ writings during their work with Pranayama—as an appropriate observation here. These may involve the occurrence of limb spasms or certain “frog-like leaps,” which precede the great art of levitation. This is a common side effect of extremely shallow breathing that an Aspirant can sustain for a long period. First and foremost, personal experimentation in this area will show us, very simply, that the sensation of heaviness disappears during a well-performed Asana. Then, by fixing the gaze and staring at a point in front of us with closed eyes, an impression of a shift in body position occurs, and we will often have no doubts that we have physically moved or tilted. When we add the continuation of breathing exercises, as discussed in this lesson, the application of everything we have talked about regarding Asana and Pranayama, the body’s sensation will bring about an identical feeling of floating and non-corporeal existence, which will, in parallel, shift consciousness to such an extent that the impression of levitation becomes a completely logical consequence. At this point, our startled mind tries to fit such an incredible achievement into its own framework of experience. In working with Asana and Pranayama, levitation is something that will be experienced sooner or later. Whether it manifests as an inner impression, an illusion, or a physical manifestation, is completely irrelevant. If the Aspirant is closer to the idea of Yoga as the achievement of Oneness, I consider this event pleasant and beneficial; without it, it is nothing but the act of the most mundane village sorcery.

In addition to physical sensations, such as phantom limb positions, body tilting, energy currents, tingling, and tickling, there is often an accompanying sense of discomfort and neurosis. This can overwhelm the Aspirant, causing unbearable anxiety that may lead them to abandon the practice of extremely shallow breathing, resorting to gasping for air as though fighting for their life. Therefore, it is crucial to prepare for this exercise by first practicing rhythmic breathing for a period of time to calm our nature. This brilliant exercise trains the mind far more than the deep inhalation exercise, which has a greater impact on the physiological aspect. Through their parallel application, the Aspirant will experience a deeply multifaceted benefit from both practices. The entirety of their Yoga will begin to radiate success, which will transform the entire spectrum of their practice. They will even notice that their Asana becomes more comfortable, lighter, and more tolerable.

I now come to my favorite and the most exalted aspect of this part of our art—the instruction to inhale slowly for no less than two minutes, at first glance a simple and naive directive. It will be very unpleasant at the beginning, but very soon, you will encounter what is described at the beginning of the LIBER HHH—a very specific kind of sweat, as well as tingling sensations on the surface of the skin. Take your breath so slowly that you barely move your lungs, as though you are expanding your lungs simply by thinking about inhaling. Carefully observe your body during the immensely long inhale, noting each subsequent moment as your lungs expand. You will notice a certain degree of inner irritation and discomfort, and at one point, you may feel as though you are running out of air. Your lungs will physically begin to quiver, as if they are in spasms, experiencing neurotic jerks as your being desperately desires air—air it has been receiving all along. More than anything, you must remain perfectly still, fully enjoying the air that enters. The only remedy in this exercise is to focus solely on that almost eternal inhale, which, from the standpoint of our nature, truly feels like it lasts forever. Throughout all our past years, our being has never been put in such a situation, and the time that passes during such a long inhale stretches and expands more and more as we continue to take in air more and more slowly. Our being will resist, desiring to escape from this trap where it might suffocate, and it will now cleverly produce impulses and irritating sensations, just as it did in Asana—itching, tingling, a strong urge to change position, to move just a little, even if it is only by one inch, to scratch for just one second. The idea of petrification and stillness in Asana has a physical component, while here, it exists in the temporal dimension, where the feeling of compressed time increases as we breathe in more and more, and the lungs become fuller. The entire wisdom of this practice is to enjoy the flow of air, which, no matter how small our being deems it to be, is constant and, as such, brings a constant stimulation of pleasure and enjoyment. All of our effort should be focused on holding onto that pleasurable feeling as an anchor for salvation. You must set yourself as though the slow inhale excites you, as if it is your way of flirting with the Universe, even the discomfort that arises should actually excite you, for this should be more of a seduction than an effort or a practice.

Once discomfort arises, it will begin to grow as the lungs fill with more air, so you must do the opposite. At the moment of neurotic discomfort that compels you to inhale all the remaining air in an instant, seizing all that your Self has patiently, slowly, and pleasurably claimed, you should slow down the pace of your inhale even more, to the point where it becomes almost nonexistent, only a pure imagination or the impression that the lungs are merely slightly filling with air. This will immediately impact the shape of your consciousness, leading you into a very specific trance. At the same time, your body will begin to express sensations similar to those experienced during shallow breathing: a feeling of electricity on the surface of your skin, at the crown and top of your head, various fine pulsations all over your body, mostly on the surface of your skin, your hair will feel as though it will stand on end, your limbs will start to tingle gently, and many other lively and cunning games of awakening forces and shifts in consciousness will manifest, each in its own way for every Aspirant.

In the beginning, you may notice that your lungs will tremble as you fill them, especially near the end. This trembling will eventually subside with regular practice, although it will make the slow breathing pace more difficult. The Aspirant must be patient until both the respiratory system and the mind adjust to this seemingly strange and unnatural action of taking an incredibly slow breath for over two minutes.

Let us revisit the entire process from the beginning. You will sit in your Asana and take a deep, three-part inhale, after which you will exhale completely; first the abdominal area, and then releasing the remaining air from the upper part of the lungs. Without much delay, you begin to slowly, almost imperceptibly, fill the lower part of the lungs, as if air is flowing through a malfunctioning, slow valve directly into the abdominal region. As the air enters, your mind will also fill with the pleasantness and joy of the life force entering, gently, slowly, continuously, and steadily. You may even make a slight movement with your lips, curling them into a nearly imperceptible smile, greeting the entry of air through your nose, infusing additional enthusiasm and joy into the practice. Firmly establish yourself in this feeling of constant, uninterrupted growth of air. Your lungs and chest will expand, not just with air, but with Will, with life, growing ever more vibrant and expansive with each moment. As the slow, imperceptible breath spreads through the lungs, you will begin to feel the irritable urge to take a sharp, full breath. You will feel discomfort, as if you need to sneeze—you inhale, expecting the sneeze, but it does not come. You raise your head toward the light, and the irritation grows, but still, it is not enough to trigger the sneeze. It is the same with this cursed thing; the irritation is unbearable, and you almost stop, shortening the suffering. But you persevere. Now, your lungs are halfway full, the air having moved from your abdomen into the upper part of your lungs. The irritation becomes more pronounced as you begin to fill the upper lungs—it feels as if this area houses many centers of our neurotic energy, which now react to the gentle influx of vitality. However, you slow your breath further. Your being begins to enter a state of pure hibernation, as if the entire system has been reduced to a single action, a single thought—just enough to keep the lungs functioning, just enough to stay alive. The urge to grasp air becomes almost unbearable; everything seems like a pointless and unnecessary task that harms the lungs and the brain, as if this practice is detrimental to your health. You feel discomfort, urging you to move, to leave Asana and seize the air right before you. But now you slow the inhale even further, compressing time and compressing your Self until it becomes even smaller, more dwarf-like. It is so small and imperceptible, as though it anticipates something inevitable that will shake the foundations of the visible Universe. It is as if your Self is waiting for an explosion of illumination, a fission of gnosis. You do not even move your lungs; they move on their own, prompted by the thought of inhaling, so subtle and tiny that it has no strength to inhale forcefully. Instead, in this hidden place, it creates the minimal action of inhale, enough to extend life but insufficient to do anything more. Your being experiences a spasm of senses, emotions, and sensations, making the unbearable irritation now feel like a strange pleasure—a mixture of the approaching orgasm of the body and the bliss of the soul, satisfying all senses, all pleasures, in a single moment. It is as if the blending of all the colors of the cosmos is now drawing a new shade on the canvas of the soul, warm and radiant. Your body begins to tremble, an electrical storm runs through your skin, bringing a peculiar, intoxicating sweat. The entire body-soul is charged with an immense force of pure pleasure and satisfaction. Until the lungs take in the last breath they are physically capable of; any further and they would burst, dispersing across all visible space and melting into the entire Universe. You come to the limits of the inhale, and then suddenly, all of this is erased by the exhale, as you return to the starting position. You exhale completely relaxed, without holding back, without any desire or effort. You are simply there to consciously pass through this release of your overstretched lungs. Just a moment later, they are empty, ready for the gentle cycle of breathing to begin again, slowly, devilishly slowly, as if we want to live out the final seconds of life, prolonging them beyond those seconds, like a merchant at a market adding an extra gram to charge more. Every subsequent slow inhale will bring our being into a deeper wave of change, bringing a new wave of catharsis and the complete destruction of our being.

In this technique, one must aim for complete slowness, but this slowness must never turn into a blockage of the breath or hinder the development of vitality. We must inhale devilishly carefully, unobtrusively, and imperceptibly. However, like a cyclist, we must constantly move forward to avoid falling. No matter how slow it is, this slowness must be purely progressive, second by second, or more, moment by moment, more and more. We must not expect air from this technique, nor should we look ahead for the end of the breath. We must, through trench warfare, second by second, moment by moment, move horrifyingly slowly forward, taking ground from the enemy inch by inch. Only in this way can the Aspirant navigate through neurotic attacks, which will gain the strength of a true mental storm. Truly, there are no words that can adequately convey the dreadful discomfort that will arise as the lungs fill more with air, and as time passes more slowly.

What was expansion in the practice of deep breathing, here is patience. A quiet and barely noticeable riding of the fragile, life-giving wave; maintaining balance on it where just a little imbalance, a slight emotional disturbance, or a little more air taken could throw us off the wave of vitality and vibrancy. It is about patience, and nothing more; that is the only thing upon which the entire success of this method depends. It does not matter in which Asana you sit, how concentrated you are or not; what matters is only the slower, unified, continuous inhalation lasting at least two minutes, without mental agitation and the desire for air.

This practice complements the previously mentioned deep inhalation exercise perfectly. It is as if the first exercise develops additional fine muscles and ligaments involved in the entire inhalation process, but in the same way, it is as though the mind follows this development, shifting its focus now to the idea of expanding the possible inhalation, as if the mind itself is adapting to the new, minimal increase in movement amplitude. Expanding the breath beyond the usual limits of the lungs and chest, training to introduce another breath of air, is such an exceptional thing in the Zelator’s work with Pranayama—every micron of awareness of a deeper breath gives a few more precious seconds in the exercise of slow inhalation, thereby deepening the trance in an increasingly fantastic direction. This brilliance in execution, this elevated method, is, in my opinion, the only true path that raises the practice of Pranayama into the domain of Samadhi. If I were to choose a single exercise from among all the forms and variations of breathwork to carry with me for the rest of my life, it would be this: the method of utmost slow inhalation.

Even after just the first few minutes of performing this exceptional technique, it will bring powerful physical sensations and generate a current of energy potent enough to stir the very foundations of the Aspirant’s psyche. Levitation, or the phantom perception of levitation, is something to be incredibly cautious about, and in my personal experience, it is easiest and even most objectively perceived with the application of inhalation prolonged for over two minutes. In my life, I have had a few seemingly completely certain impressions of the manifestation of this siddhi, but I always regarded it as a secondary consequence and manifestation of the path, which in my case has always been enlightenment. Without it as a carrier, I am almost certain that I would not have been able to experience any of this, not even as a slight impression, nor as the strange sense of swaying that sometimes followed sudden jumps and jerks of limbs that had truly exceptional physical strength—as was also achieved through other forms of Pranayama. But in the case of the slow inhalation exercise lasting over two minutes, the only further certainty that would confirm the objectivity of the siddhi is a camera recording, which I do not have. Not because I was afraid that a recording would show the strength of my imagination and the phantom impression of levitation, but simply because my primary motivation was, in fact, anything but the siddhi—only the bliss that appears in the Aspirant at the moment when this sense of flight arises secondarily is so inviting, and above all joyful, like a cosmic joke that the Universe has shared with me in its silent language, and now, finally, the punchline of that ultimate joke reaches my mind. The burst of laughter when this state is achieved is some strange mixture of humor, enthusiasm, and pure joy, where the physical smile is always the accompanying achievement of that state, alongside the sensation of pure floating, and my physical hands that would not touch any physical surface. Truly a strange and fascinating feeling; certainly, the practice and experiment with all the exercises outlined will give the Aspirant the only correct judgment about the objectivity or complete subjectivity of this phenomenon. Certainly—setting aside the fact that I hold a firm conviction that any claim of physical levitation unmistakably points either to a mental disorder or, at best, a particularly elaborate falsehood.

I would like to add a few words about a phenomenon that is strikingly similar to the occurrence of “jerky jumps,” which are always precursors to the sensation of levitation and which certainly deserve more exploration through the method of scientific illumination. This phenomenon is the occurrence of sudden, unpredictable jerks, like a brief electrical shock running through the spine from the torso down, mostly experienced during an afternoon nap. It is nearly impossible to find a person who has not experienced these body jerks just before falling asleep, especially during an afternoon nap or when we are exhausted in the evening. The state of an afternoon nap is particularly interesting for studying lucid awareness because, in this state, our mind directly enters REM sleep, bypassing the “blank” nREM phase that is so characteristic of the beginning of normal evening sleep. The interruption of electrical impulses from the neck down, which marks the REM phase—an insufficiently researched and brilliant area of our mind that, I am certain, holds many answers to our spiritual questions—sometimes results in a peculiar discharge, manifesting as jerks in the arms and, particularly, the legs, as a reaction to the body’s insufficient readiness for sleep. The mind applies several layers of checks before it activates the REM phase and interrupts the electrical impulses from the neck downward, leading to the paralysis of the body from that point down. Ensuring that the body has indeed acquired the ideal conditions for sleep is part of an ancient mechanism that has been evolving for thousands of years, which, in its perfection, still possesses flaws and gaps in the system that the cunning Aspirant uses to consciously enter the realm of dreaming, when brain activity is far greater and deeper than in the waking state. In this way, the Aspirant uses this state for spiritual travel, performing numerous exercises and rituals within this plane, in a form of attainment known as lucid dreaming. This is thoroughly explained both theoretically and practically in the instructions for the Neophyte, to which the interested individual is encouraged to refer. I am certain there is a strong connection between the occurrences of the levitation siddhi, the “jerky jumps” that precede and lead into that siddhi, and the jerking of limbs that can appear just before sleep, most often during an afternoon nap, when the REM phase is much more open and closer. The intertwining of the brain’s REM phase with the supposed levitation siddhi gives this artistic work of the mind a completely different nuance, one that seems much more human than otherworldly. It is much more logical and rational, much more grounded, than floating and incorporeal, as many wish to portray it. The connection with Pranayama could also be found, given that all these things are tangled up in a much more complex cause—the brain and its REM phase. We will certainly discuss this phenomenon more later, in greater detail, in the exposition on sex magick.

We should also say something about the specific manifestation of neurosis that arises during the technique of slow inhalation, and which is also present in many other forms of Pranayama, where the breath is expanded, calmed, and slowed. Practical experience will show us that this begins imperceptibly, but quickly intensifies, becoming unbearable as our lungs are nearly full of air. We will notice that the change in awareness, which will drastically manifest with each passing second in slow inhalation, actually has nothing to do with the amount of air, but is rather a consequence of our resolve not to succumb to the neurotic impulse that urges us to gasp for air. It is as if, in the midst of panic, our mind, overwhelmed, will open a backup channel, directly supplying cosmic energy to sustain the Selfhood, as if in this distress, a completely new channel to the Selfhood will unexpectedly open—allowing the flow of unimaginable energy and a completely different and altered awareness. This is the same root of the neurosis that appears in its altered form during Asana practice, with the urge to move, stretch, adjust our legs a little better, or twist our sleeve that bothers us, or the appearance of itching that increasingly distracts our practice, which so mysteriously vanishes the moment we give up and get up from Asana.

Let us observe our body during the process of falling asleep and notice the excessive tension that prevents the sleep mechanism from functioning properly. A seemingly insignificant urge can often be the main, if not the only, cause of insomnia, and its habitual presence can prevent an Aspirant from falling asleep easily for years. The only solution is awareness. Everything begins the moment we lie down ready to sleep, but in that moment, we might think it is better to turn to the other side because the airflow seems better from that position. At that very moment, with the simple act of turning over, we unlock an urge that begins to grow and develop like a raging river. Shortly after, we may feel the need to urinate, and once we get up, we might drink some water. This cycle does not end once we return to bed. Quite the opposite, it continues. In just a few moments, the pillow begins to heat up to the point where we will feel the need to flip it over. Then comes the itching—first on the head, then on the arms, one hand, then the other, the knees, and finally, the overwhelming thought about some utterly meaningless problem starts to occupy our mind. Just when we decide to push it aside, the urge to visit the restroom appears again, triggered by the glass of water we drank earlier. And now, while feeling angry because of the full bladder it created, we realize we are still thirsty. Finally, after emptying ourselves and drinking less water than before, we lie down again, feeling tired, but just as we begin to drift into the pre-sleep state, we hear the buzzing of a mosquito—something we can not stand, to the utmost.

All we can do, and all we need to do, is resist the urge to move. For one movement leads to another, and another leads to the third, and suddenly, from the frozen, static image of oblivion and the deep tranquility of sleep, we begin to play a film reel, an endless reel where movement creates the illusion of activity—an activity that our unconscious mind now defines as something it must follow, like an interesting movie that nature now watches with curiosity. Soon, the desire for sleep becomes anything but that. Instead, we are awake, even more awake than we were before lying down, and our being, completely bewildered, produces a new neurotic attack, projecting the thought that this will continue until morning, and we will wake up sleep-deprived, a thought that is beginning to manifest and solidify in reality.

I want you to do the following next time you feel hungry. Prepare your favorite meal, or go to a restaurant and order the dish that your hunger guides you toward—whether it is a fruit salad, a rich sandwich, or a delicious pasta with your favorite sauce. When the meal arrives, I want you to pay attention to the first bite, choose the best, juiciest part of the dish, and take it slowly, focusing on the sensation of hunger. Now, I want you to chew that first bite as slowly as you can, refusing to swallow that wonderful blend of flavors. Chew slowly to the point of exhaustion, as if in slow motion, until the food in your mouth becomes a tasteless mass. Prevent even the smallest micro-movements that allow saliva to move the food down your throat. Chew endlessly, savoring the hunger, and observe the fantastic phenomenon that arises—the same discomfort as in Pranayama during slow inhalation. It is a truly remarkable phenomenon, very specific and authentic, that you will immediately recognize in its nature, as well as the effect it has on your mind. That inner urge, from within yourself, forces you to do something that is against your own nature. It is so hypnotic, so enchanting, that it almost feels like a spell compelling you to swallow that bite. With every moment of refusal, that urge seems to grow, piercing you more painfully, pressing harder, more and more, until you finally give in and swallow that bite. I want you to carefully observe this neurotic behavior, which completely changes its form when you finally swallow the bite. It does not vanish; instead, it temporarily recedes, still holding its sharpened weapon, ready to strike again, more quickly, more fiercely. The next few bites are chewed and swallowed normally, as if the first bite was just a tasteless joke, and then, once you are settled into your usual eating rhythm, take another bite and do the exact same thing as with the first one—chew it slowly, with no intention of swallowing it. Now the neurotic behavior will appear more viciously, to the point that it will feel as though we are being pricked by thorns, as if an electric impulse is radiating from our stomach, our spine, our brain, paralyzing us and turning our body into a hypnotized slave—its only purpose being to swallow that bite, the fate of its existence depending entirely on it.

Now, I would like you to try something completely simple—yet no less revealing. This small experiment might be the most effective way to give you a clear and immediate insight into the true nature of your neurotic tendencies.

Place a spoonful of olive oil in your mouth and start swishing it around for five minutes. After just one minute, you will experience a completely unexpected urge to either swallow or spit out the entire contents. This neurotic compulsion, the idea of discarding what is in your mouth, will begin to haunt you the more you swish. This is an excellent exercise for calming the mind; all you need to do is endure for five minutes, and any thought about time or the eventual need to spit out the oil will only hinder your progress. Let go of everything, completely detaching emotionally from all thoughts. The five minutes will pass quickly if we do not desire them to end, and instead of focusing on time, let us focus on the act of swishing the oil in our mouth, turning it into a game. Simply, swish the oil around in your mouth, continue doing so, without any thoughts, without philosophy—very simply, play with that contents, letting it pass through your teeth and over your tongue, enjoying this divine and simple game, the feeling of the oil caressing and cleansing your mouth. As time passes, the discomfort and the urge to swallow will feel exactly like the compulsion to take a breath in the slow-inhale Pranayama—an identical mechanism, just in a different form, in a different disguise. I want you to direct all your attention to this unbearable urge and see it as the same thing I asked you to do when you were swishing the oil in your mouth: a playground. Explore that urge, observe it, measure it, and respond to it in the same way it captured your nature—through pressure, focus, and awareness. You will see that the discomfort quickly fades when surrounded by your attention, and instead of discomfort, you will feel a vast reservoir of energy, pure power that your unconscious being has unintentionally left behind because you gave it the wrong coordinates for attack. A strong focus on the unbearable urge to swallow the oil, as if you want to intensify it, as though you want to help it become even more unbearable by directing all your thoughts toward that unendurable feeling, will appear to be the mortal enemy of that very urge, which weakens and dissipates through your focused attention. Instead of struggle and discomfort, you will witness the birth of an entirely different energy, like its negative counterpart—which will radiate positivity and pleasantness above all. Now, direct that pleasantness toward your breath; inhale, imagining you are expanding it further. Your attention will now be even more engaged in this action, which will act as a focal point for the pleasantness, filling every cell of your body with life-purifying energy.

Mahasatipatthana, much like the practice of Asana, finds its ideal ground for experimentation within Pranayama–where it can lead to intensely immersive meditative states. The breath comes in, the breath goes out. It is the air entering the lungs, filling them, only to leave again in the next moment. Then, we have the lungs, and finally, the space within the lungs that contains the idea of both the air and the lungs together, and ultimately, it is life sustained by the lungs through the movements of inhalation and exhalation, which continue constantly, perpetually, driven by the conscious will—not for life, but for the will to live. Now let us apply Mahasatipatthana to its mirror state: when we inhale, it is as if the non-self exhales; and when we exhale, it is the Universe outside that inhales. Mahasatipatthana on the discomfort caused by slow inhalation, as previously explained, is a perfect opportunity for self-realization. Let that discomfort now become the focus of the Aspirant’s work; let them observe “that” discomfort, which increases as “that” inhalation deepens. Let the increase in discomfort be perceived as the lungs expand, and let the Aspirant realize “that” increase as it is relevant to “that” body whose lungs are filling more with air. Finally, let them independently observe the neural spark appearing in the nervous system of that body as the breath approaches its end. Let them conclude that the neurotic tendency induced by the slow breath appears in the brain’s centers, as a result of irritation in those regions accustomed to a different breathing pattern than what is currently happening in “that” body. Let them conclude the “Mahasatipatthana” performed by the Will of the Aspirant, and observe all the effects of slow breathing used by “that” same Aspirant in “this” very Mahasatipatthana. Finally, let them leave that stage and abandon the theater where this entire process was enacted, prompted by the very instruction they have just now read—even in this very moment—receiving an impression that will shape the entirety of “that” Mahasatipatthana.

This is a golden exercise that a Zelator can fully isolate as a separate branch of their daily work; such are the fantastic regions into which their being can enter through the application of all these techniques. What initially seems as mundane as Pranayama or Asana can now serve as a chest full of jewels.