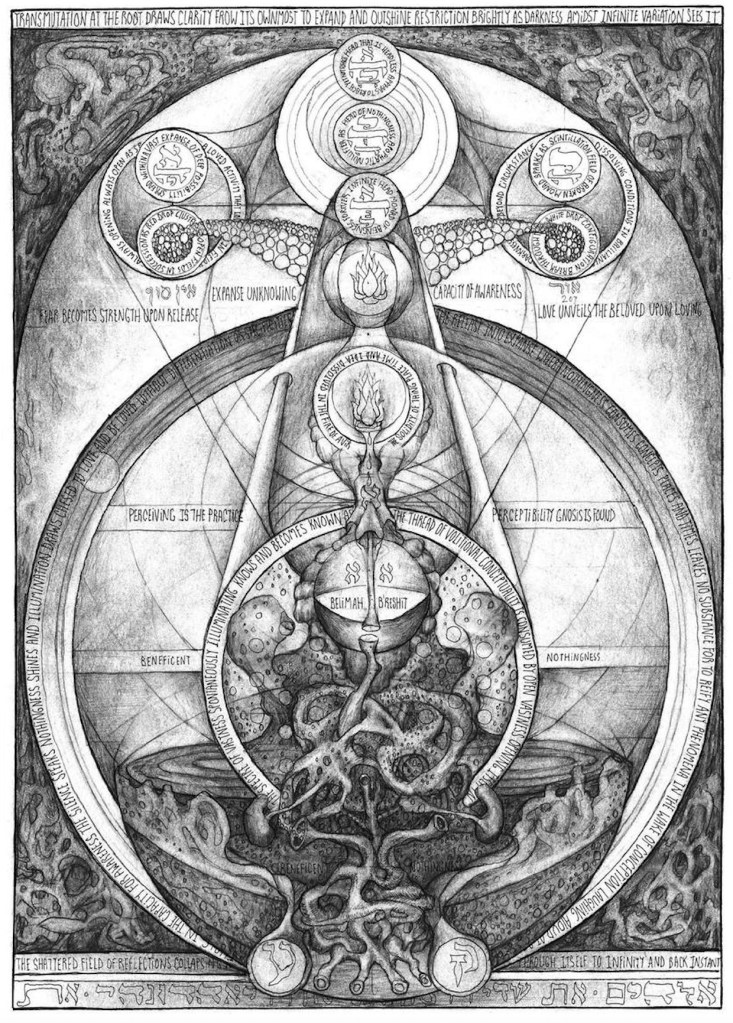

In various esoteric traditions, the Moon is a powerful symbol of transformation, reflection, intuition, and the depths of the subconscious mind. Governing the tides of emotion, it embodies the cyclical nature of existence and represents the receptive, feminine aspect of the psyche. Within the Zelator grade, the Moon serves as a metaphor for the Aspirant’s journey into the veiled and often uncharted dimensions of their inner nature.

The phases of the Moon—waxing, full, waning, and new—mirror the stages of personal growth and transformation experienced by the Zelator. Each phase reflects a distinct aspect of the Aspirant’s development. Just as the Moon does not generate its own light but reflects the radiance of the Sun, the Zelator contemplates the inner light and the knowledge imparted through the curriculum. The Moon’s cyclical rhythm mirrors the Aspirant’s path—a journey of rise and fall, expansion and contraction, where progress is not a straight ascent but a continuous flow of integration and renewal, triumphs and setbacks, effort and repose. Through these cycles, the Zelator learns that true advancement requires both movement forward and the assimilation of past insights.

The Moon’s dominion over the subconscious mind underscores the Zelator’s task of navigating the hidden recesses of the Self. This path demands the confrontation and integration of the shadow, leading to a more complete alignment with one’s Pure Will. As the Moon governs intuition and emotion, the Zelator must learn to perceive and master these forces, refining instinct into insight. Emotional discipline becomes a vital aspect of this work, for only through understanding and directing the tides of feeling can the Aspirant bring their subconscious into accord with the sovereign governance of the Will.

Within the A∴A∴ system, the association between the Zelator and the Moon emphasizes the imperative of introspection, emotional cultivation, and the cyclical nature of spiritual refinement. The Zelator, as seen on the Tree of Life, is for the first time freed from the Earth’s gravity and its influence, and at first glance, this path is significantly eased and elevated by a completely new body in its stellar journey. The value of the Moon lies precisely in the fact that it is close enough to make us feel safe and under the protection of the familiar surroundings, yet far enough for us to believe we are entrusted to the vast and glittering unknown. The Moon, therefore, serves the Sun and is its extended hand of action. It does not radiate light on its own, but shines in the same way as the other planets in the system, yet it is the brightest. It is the light that a child’s soul, frightened and unsettled by the dark expanse, upon stepping into the unfamiliar part of the city, can accept openly because it gently brightens the way, dispelling fear. Just enough for them to see, but weak enough that they do not become reliant on external help, it teaches that the path ahead is long, perilous, and unyielding. The Moon is much like a parent steadying our bike as we learn to ride. At just the right moment—once we’ve eased into trust—they let go, and without even realizing it, we continue riding on our own, confidently and joyfully. Forward, inspired, devilishly brave, devilishly fast.

Yet all these generalities offer us little of true value—nothing particularly useful, I would say. What we need is a scent to follow, something that will drive us relentlessly, like a bloodthirsty hound, forcing us deeper into the savanna of the soul, in pursuit of the mind’s prey. Memorized verses and endless recitations about vast mental landscapes and the boundless rivers of the Self will not quench our thirst. On the contrary, they will only make us thirstier. We need something else—something alive. A different, more natural, more personal way of seeing things. Sometimes in our art, we do not need a clinical term for the female reproductive organ; we need a cunt. We do not seek sacred tantric union; sometimes, we just want to fuck. Pure, unambiguous, raw, beautiful fuck.

We do not need the phases of the Moon to remind us of the existence of our mutable emotional apparatus, the existence of the entire concept of change that is an integral part of every existing cell of the soul. The problem I foresee in advance is that, among all the dry theories and postulates about the necessity of the transformation, transcendence, and the evolution of our nature, the now tiresome proclamations such as “the only constant is change,” is that from such boredom, all these cells now undergo a completely wrong transformation, for from the immense monotony, they have become cancerous, devouring the very organism for whose well-being they initially began to change. Therefore, I would suggest a more personal approach, one that strikes at that feeling of instability within us, that acid which corrodes our being, which tightens and presses us every time we think we have achieved peace and a state of constant happiness, when the feeling of anxiety and unease arises in us, without any reasonable explanation. Just when we have mastered the ritual, struck the perfect vibration, held Asana for an hour without a single hidden itch or flicker of pain—just at that moment when we whisper to ourselves, “success!”—like some twisted echo of the amateur’s pride, the Universe responds. His triumphant “success!” ricochets through the farthest corners of existence, only to return, unmistakably clear: “no, failure.” You have certainly already encountered that peculiar dark humor of the Universe, where whenever things go well, something worse appears. It would never have appeared if there had not been something good in the first place, as though it were some evil and corrupt game, in which you are the subject of cruel, mocking humor between divine heights and the darkest hell.

But if you are fine, then nothing.

This change, poetically, mythically, and with a juicy, romantic expression embodied in those beautiful and magical phases of the Moon, the Aspirant observes not as an objective truth, but as a subjective lie. In other words, they reflect light in exactly the same way, showing that change and entry into phases are actually experienced by us alone. The Moon reveals exactly what we are; it does not enter any shadow from which the light of the entire sphere cannot be seen. What is not whole is ourselves, who project this incompleteness onto another body. But even that other body, if it exists, is part of our system, in which our Sun is the master, around which everything revolves. The Moon is only a mirror; its phases are only our own.

The Neophyte’s approach to neurosis already carries the imprint of Moon’s nature, a theme explored in depth in my previous book. The Zelator follows the same route but will disembark at a far more distant station—one much farther north, where the cold bites deeper and the darkness grows heavier.

The psychology and psychotherapy of our time, with all its endless directions and variations, has given us a wonderful pill that, once swallowed, convinces us that the pill is responsible for everything, even that it made us swallow it. Moreover, it is to blame for all our flaws, projections and neuroses, fears, and all the destruction we express outwardly as much as toward ourselves. It is no longer fashionable to remain unaware of the darkness we harbor; we have, at last, named the villain—and mercifully, it is no longer us. We observe that this is some process within us, which has a reason and a mechanism of its creation, its appearance, and its operation, but our role is reduced to that of mere witness: to recognize and become aware, never to intervene. We have found all these foreign bodies, invented the telescope, and now we know that the new Moon is the same size as the full Moon, only that light illuminates it differently. The eclipse of the Moon is now a fully understood phenomenon, as is the eclipse of the sun, but when the topic is the eclipse of the mind, the eclipse of our nature, then it is time for another pill and another carefully measured forgetting.

Today, it is entirely acceptable to acknowledge that our own processes are the ones causing the problems, and that the evil within us is, in fact, a repressed and distorted form of good. However, the Zelator begins to realize that it does not matter what is happening with the celestial bodies at the moment of the great eclipse. What truly matters is how much they can exploit the darkness for whatever benefits it may bring. While everyone else keeps their gaze fixed high above, they are the only one who crawls, observing everything around them like a divine thief, daring to steal nothing less than the fire of the gods, precisely when no one is watching. It is not about what happens, how it happens, or to whom it happens. The crucial thing, my boy, is what you choose to do with all that damn chaos. That’s exactly it. And the Zelator knows precisely what he will do and how he will do it. It is his sacred duty—to act without hesitation and to forget with deliberation, free of regret, free of doubt.

The Zelator does not seek a culprit; the Zelator hides their own tracks, for they know that they are the perpetrator. From the perspective of the Universe’s mechanism, the Zelator is not an ordinary witness; they do not testify to things that do not interest them. They are a false witness, testifying only to what suits them or to what benefits someone else more. For the Zelator knows that no matter how hard one tries, no one can know the One Truth, and so every testimony is both true and false, except in one case, of which there are infinitely many. It can be said that for the Zelator, the Moon is neither a sphere nor a dwelling, but a refuge and sanctuary. It reflects and deflects what gives us the possibility of illusion, self-deception, and lies. It presents us with light, as the idea of the highest enlightenment, without which no lie could be established, making every perception, even the perception of truth, a subjective and limited filter. Thus, the Moon is the whisperer of deceit, the midwife of corruption.

It is quite convenient to think of the Moon as a layover, a connecting flight to our final destination, for which we have purchased a one-way ticket. It would be disastrous to mistake the Moon—and all those astral realms that stir the soul with a spectacular tremor and evoke a singular euphoria through their nature and utterly distinct landscapes—as anything crucial enough to divert us from our course toward the Sun. This is wisely reflected in the placement of Yesod on the Tree of Life, which serves as a mere waypoint along the Middle Path leading to the Sun. It is as if our ancient brethren left this marker on the map—there to be found, yet harmless—positioning these experiences so transiently that we may gather them without even slowing the course of our chariots of fire.

Indeed, Aspirants can remain blinded for years by this magnificent plane of the Universe, which is nothing but an unexplored partition of their own mind, a passage to a neighboring area they have never walked through, simply because they have never had any reason to do so. Yet, those few who are aware know that this passage is itself the destination. It holds a reason that is enough to guide us not to pass through it and go somewhere further, no, not at all. Instead, it compels us to stay in that passage, for within it lies a city where we live upside down. This passage offers an entrance to a completely foreign city, an underground landscape with its inhabitants who never go outside. And all these inhabitants are like us—our neighbors, who have never used this passage, just as we never did, because there is truly no benefit or logic in it. It does not shorten any possible rational path, it does not cut through any street, it has no traffic, nor can it be used to escape the urban chaos. There is no convenient space to park a car when it is impossible to do so anywhere around during rush hour. In fact, the Great Architect, whom the Zelator will meet, created this secret passage precisely because he wants those who gain no benefit from it. Those who use it only for their own fantasy, as some Feng Shui for their mental perversions. It is precisely such people that the Great Architect calls to be the elite guests of this lower city, down below, deep in the inverted underground. And down there, the city takes on its true, vast dimensions. For all that is interesting and good is found down there, deep below.

Indeed, the Zelator does not draw strength from the idea of “dwelling” as does the Neophyte, who studies and masters the ability of lucid dreaming, a concept whose essence is symbolized by the Ritual of the Pyramid. Instead, the Zelator draws strength from the idea of “passage,” which in turn embodies the idea of the “Ritual of Passage through Tuat.” The essence is not so much the realm of Tuat but the act of “passing through it.” The Zelator’s ability, which they refine to the extreme, is not lucid dreaming, but passing through veils—through the fine layers of sleep, through the veils of the mind. The Zelator will perfect the prolongation of their stay in lucid dreaming to the utmost, and will also learn to maximize the clarity of the astral plane, to such an extent that the surface and contours of the dream will become so solid and real that they will have to resort to special tricks to break or to pass through them. The ability of teleportation, or the sudden change of dream scenarios, is of particular importance to the Zelator, a topic we will approach more carefully later in the book. However, we have already covered this well and in detail in the book on the Neophyte, so we will not linger here except to mention it for clarity. The idea of “passage” will be further elaborated by the Practicus, who will master a completely different method of experiencing other planes, one that is entirely specific and so different from lucid dreaming: the art of scrying.

The idea of “passage” will find its foundation equally in the skill of Asana and Pranayama. Through Asana, the Aspirant will pass through the experience of their own physicality by altering their perception of the body, thereby changing their own consciousness within that physicality—passing through the layers of the coarsest physiology, the itch, the pain in tendons and ligaments, the spine and neck, all the way to the subtle sense of wholeness, which leads to automatic rigidity, and finally, when both their consciousness and physicality become merely carriers of the Self, they will pass, through persistent practice, from the gross to the subtle, from the manifested to the complete cessation of body awareness, pain, or position—all within the vast emptiness and the aphrodisiac of Sunyata. With Pranayama, they will pass through various rhythms, tempos, and methods of breathing, awakening the subtle energy to the level of physical sensation. Thus, they pass through all of this—through waves of breath, through the trembling of internal heat, through flickering sparks of energy—but without becoming attached to them, without euphoria, without sanctifying the process. For therein lies the trap: what should be a passage in many modern schools and systems becomes a stopping point, transformed into dogma beneath various titles and cloaks—Yoga, Kundalini, Tantra, or Kriya.

The automatic consciousness that the Zelator attains, and which is especially important in their work with Pranayama and in the precious aspect of working with Asana, is a process that is gradual, patient, and above all, conscious. The stiffness of a stone statue, for instance, is possible as a very gradual achievement, in which the Aspirant remains present with their attention throughout, and where they observe the change in their bodily experience, which would be impossible without their attention to that change. It appears slowly, and this slowness increases drastically if it is awaited with the desire to rush. It is almost impossible to achieve complete stiffness in Asana in a short time, no matter how experienced the practitioner is. Unlike some other achievements, which may even seem miraculous when viewed through the eyes of an uninitiated amateur, such as scrying, Enochian invocations, or even the transfer of consciousness into the Body of Light—the achievement of Asana still requires a longer period. For it is precisely in this time, in this “passage” through the gates of time that alter perception and even change awareness completely, I would say even the subject itself, that contributes to the fact that it is always so gracefully accepted. At least by those who learn to perform it correctly, while for those who experience it as a dry lesson in algebra or a task in grammar, all of this becomes a demonstrative exercise in suffering.

Automatic consciousness, or rather alertness, embodied in the idea of the Moon, contains the complete assimilation of that idea, just as the Moon appears in two vastly different Atu— “The Fool” and “The Moon.” The automatic actions that characterize the Zelator are not limited to the solid and material Moon, as the parallels in the practice of Asana and Pranayama. In the aspect of The Fool, it is a matter of working on lucid awareness, containing a special kind of conscious and uninterrupted transition toward dream, where the ultimate goal is completely opposite to sleep. It is awareness and alertness, but on a different ground from where alertness is normally found. In the lucid experience, we are certainly awake, even overly awake, but within the dream’s frame. The entire world and environment where this wakefulness manifests changes completely. We have covered this in depth in the instruction for the Neophyte, but here we will focus only on the detail that is particularly important for the Zelator, and which can transform any of their sleep into a supreme astral experience, which, in its specifics, has distinctive value for this grade. This detail concerns the deeply ingrained habit of moving and opening the eyes after waking. This habit is so ingrained in us that even mentioning it evokes a certain sense of absurdity. It is completely impossible to assume that a person could wake up without moving or without opening their eyes. Yet, persistent practice completely breaks this outcome; all that is necessary is to repeat an affirmation before sleep, so that we wake up without moving or opening our eyes. The affirmation is always in the present tense, always in the potential that is realized, not one that will be realized.

Therefore, the affirmation should not be: “When I wake up, I will remain still and without opening my eyes.” The correct form is something like: “I wake up without moving or opening my eyes.” If we fully adhere to the instruction about positive potential, then we can transform this into: “I am awakening in complete stillness.” In terms of the magician’s creativity that defines our artistry, we need to introduce one more detail and link that will support the manifestation of the affirmation, like a lighthouse guiding our nature through the dark waters of unconsciousness. This detail is the emphasis on “remembering,” or that we will “remember” to stay still and not open our eyes as soon as we wake up. That small detail acts like a lever in the transfer of weight, easing the entire process. The focus is not on simply hoping that we will wake up without moving, which may happen tomorrow, a month from now, or perhaps never. The repetition of the affirmation must be supported by a clever detail that will bring about the condition, and that is that we will remember. And we will remember as soon as we wake up. Therefore: “I remember to remain still and without opening my eyes as soon as I wake up.” Also, avoid completing the affirmation with something like “after every waking,” because our unconsciousness at these moments does not recognize the language and ideas available to our waking consciousness. Hence, “after every waking” is a broader and more indefinite concept than “as soon as I wake up.” Our intention holds a passport of the moment— “as soon as I wake up” belongs more to the land of immediacy than “after every awakening,” which feels more like a resident of tomorrow.

Also, ease the entire process by using tactile stimulation for what is contained in the affirmation. This means, lock the position of the physical body from the moment you give the affirmation. Simply, do not move from the moment you give the suggestion until the moment you wake up, at which point the affirmation will activate, now with all the necessary conditions to be fulfilled, not by random predictions but by active recognition of the correspondence, which your unconscious nature does almost automatically. This is the process that is so crucial for the Zelator—automatism.

Making an affirmation is glued to the determination not to move, so our body will remember the affirmation along with the position, which, being unchanged and motionless, reinforces the affirmation and intention to stay still after waking up even further, rounding off the idea at a much wider and more compact scale. In a way, repeating the affirmation with a determination not to move until we have fallen asleep seems to lock information about the continuity of the position in the body, which will automatically turn on after waking up. It is simply unimaginable to guess how many miracles there are in front of our noses if we manage to do such a simple thing. Such a small thing triggers a myriad of mechanisms that make it possible to experience something that sheds an entirely different light on everything we do in life. All the rituals, meditations, techniques, everything we perform in our art is really nothing compared to the realization of lucid consciousness that begins with such a nebulous instruction, such as the instruction to remain motionless with our lids shut after waking up.

Those golden moments of our existence, those first few seconds after waking up that separate us from the just-completed REM phase, which adorns the widest and deepest functions of our being, are so easily discarded by our habit of almost panicking as we leave the bed, rushing into a world we often face by force and necessity—work, university, obligations. Once we move, once the brain receives the assurance that we have escaped the sleep paralysis and are finally awake—ready to take on the process of self-maintenance that we both desperately need, constantly, daily, endlessly, it cuts off every opportunity and possibility for us to return to the sphere of its natural habitat, where we can perform such fantastic, miraculous things. We flee from the bed as though it contains traps and diseases, as if it were cursed, teeming with pestilence, when in truth it is our throne—the sacred domain where we reign closest to our Selfhood. Therefore, the most important, crucial thing for the Zelator, as well as for the Neophyte still in their lucid dreaming practices, is to establish the vital habit of awakening without moving and opening their eyes.

We must not turn the affirmation into a button or a command for self-destruction. The affirmation must live; it must nourish the mind with its liveliness, which will then play to it like a beautiful melody. The mind will accept it with pleasure, beginning to dance and skip, forgetting the time and its remaining duties, living in that melody and dance as if nothing else matters. To achieve this, we must avoid the parrot-like repetition that leads to boredom and rejection of the affirmation. We need to enrich the practice with small details, embellishments, and ornamentations in the music of the mind, which the fine details will embrace with joy. It will truly become the beat to which the mind will not only dance but also enjoy such a divine play, a magnificent waltz of the Self.

Say the affirmation incredibly slowly. Try to pronounce it so slowly that the slowness gradually intensifies, as if you want to stretch it out infinitely, never allowing it to come to an end. We need to maintain the essence of the sentence without letting it drag on excessively; imagine it like a record that has malfunctioned, making the words stretch endlessly, like “laaastttiiiiing… for… sooooooo… looooong…”

Another powerful technique for ensuring an affirmation resonates deeply within our unconscious mind is to vary the pace of its repetition to an extreme degree. Begin by repeating the affirmation at a normal pace for a few minutes, then gradually increase the speed until the words become almost indistinguishable. The key is to eliminate any pauses between words, allowing each sentence to flow seamlessly into the next without breaks or full stops.

“IamawakeningwithoutmovingIamawakeningwithoutmovingIamawakeningwithoutmovingIamawakeningwithoutmovingIamawakeningwithoutmoving.Iamawakeningwithoutmoving.Iamawakeningwithoutmoving.”

After a while, and it only takes a few minutes, a specific state will be created—a feeling in which the frantic repetition of the sentence sculpts our mind in a unique way, as if a quick mumble has filled the void with a distinct sensation, subtle yet relatively constant. Now, stop repeating the affirmation and focus on nurturing that feeling. This is the imprint of the affirmation in our mind, resonating like an echo. If you keep this sensation in your mind, it will deepen the affirmation’s imprint, even without the need to repeat a single word. Simply maintain a gentle and pleasant focus on the feeling that arises after the rapid repetition of the affirmation, and the process will be complete. You may even sense a tension in your brain, almost burning from the intense repetition; all it takes is to nurture that flame with your attention and let it spread—this is how you can repeat the affirmation in a more advanced way, without the need to utter a single word.

An excellent technique for imprinting the affirmation into the mind, which is extremely effective and, in many cases, can bring success in using the affirmation for waking up without moving or opening the eyes, sometimes after the first few attempts, is repeating the affirmation with emphasis on different words.

“I AM” awakening without moving.

I am “AWAKENING” without moving.

I am awakening “WITHOUT” moving.

I am awakening without “MOVING”.

It is important to highlight the manner in which the affirmation is spoken. In addition to repeating it aloud or silently, a highly effective way to impart the affirmation is by voicing it in a whisper. When using this method, our attention is stimulated and provoked to increase, lifting it and, in turn, allowing the intention to be better imprinted into the mind. Another, highly penetrating method involves repeating the affirmation through all three conjugation forms, which helps to avoid limiting subjective perception and helps anchor the affirmation more firmly within the depths of the unconscious.

First person–the classic form of the affirmation, where the focus is on one’s own identity: “I am awakening without moving.” Second person–addressing oneself as an external entity, like advice coming from beyond the internal dialogue: “Dušan, splendid! You are awakening without moving.” Third person–observing oneself from a neutral perspective, which gives the affirmation additional objectivity and imprints more powerfully: “Well, well, Dušan is awakening without moving,” or: “Look, Dušan is awakening without moving.”

The last method proves especially effective, for it bridges different levels of inner perception, making the entire process shift through the lens of the aggregate states of the Self–I, You, and He/She. The first person singular directly activates identification, the second person singular allows the acceptance of the suggestion, while the third person singular shapes the affirmation as an observable fact, reducing the ego’s resistance and allowing for a seamless penetration into the subconscious. It is precisely in this combination that its power lies–the affirmation is no longer just something we try to believe, but becomes something that already is, not only for us, who might not believe, but also for someone else who is united with us in the same conviction, making us solidify our intention, as much in the faith, as in the fact.

But the seeker of our Academy approaches affirmations and autosuggestions through the lens of scientific enlightenment, never as a mechanism of parrot-like commands, where we simply hope the whole thing will succeed on its own. For us, affirmations are much more than mere mental exercises–they are tools for shaping the Will, a finely tuned instrument that can bridge the interval between who we are and who we aspire to become. Their power lies not only in the words, but in the way we use them. The aim is not just to utter the words, but to imprint them into the very structure of consciousness. When the affirmation becomes part of the living flow of thoughts, it stops being a possibility and becomes a certainty. At that moment, we do not use the affirmation to attain something–we use it to remember something that was achieved long ago. We do not need to do something, but to remember when we did it. Not to succeed, but to remember when we succeeded last time.

The nature of an affirmation is fundamentally different from that of a mantra, and much of its weak impact or failure can be attributed to the Aspirant’s misunderstanding of its function. Repeating an affirmation in the same monotonous manner as a mantra yields only initial success; the mind quickly becomes desensitized to it due to its predictability, repetition, and lack of engagement. Therefore, it is essential to infuse affirmations with vitality, movement, and flexibility, as previously described. Even singing an affirmation can significantly enhance its effectiveness and manifestation.

It would be wise for the Aspirant to use all these methods, introducing their own variations or modifying the ones mentioned above. The more varied the methods employed, the deeper and more vividly the affirmation will be imprinted in the mind, making it more effective. Affirmations and the mind are like fish and a pond; a fish can be caught in many ways, and the more different baits and rods we have, the better our chances are. However, it is not enough to just catch the fish, we must also strive to keep it alive once it is in the net. Similarly, endlessly repeating the affirmation is not sufficient; we must ensure that our mind receives and nurtures it so that it begins to bear fruit. Repetition that is too static and uninventive will create resistance to successful techniques, which will be evident in our work. We must continuously and consistently advance our methods, constantly introducing new elements and changing forms and routines.

We must never repeat an affirmation during the day, nor shall we think that such repetition will increase our chances of success. On the contrary, in this way, we are causing our being to resist and create a habit of interpreting the entire affirmation as a routine, distant thing, which is absolutely unacceptable for us, like relying on a prayer for salvation rather than using a GPS to navigate more efficiently through the tempest ocean.

It is of great importance that the affirmation is made with conviction and with the feeling as if we have indeed awakened and are motionless all the time once we have woken up, suggesting this we are experiencing a false present—such a small detail makes such a big difference from the mere hypnotic and parrot-like repetition of the suggestion. From the moment we start making an affirmation until we fall asleep, we must remain in a single position without moving, thus giving importance to the idea of continuity of immovable position, which will eventually continue after waking up. In fact, with all these elements, we frame the immobility of the body and the continuity of one position on both sides of dreaming, both before and after the dream, providing additional inputs to our unconscious mind that will drastically increase the chances.

After working with the affirmation for a while in the lively and vigorous way we have presented, we should try to fall asleep without moving, just as we would expect to wake up. Two outcomes are possible.

The first, quite likely, is to wake up moving and opening our eyes, get up and go to the bathroom, or start preparing breakfast only to realize that we have missed the opportunity and that the affirmation was not that deeply enough imprinted to be able to attack the habit of moving and getting up. As soon as we realize that we have failed, we should go back to bed immediately, pretending to have just woken up and been amazed at how we found ourselves motionless and with our eyes closed. We should act out that situation as if it has just happened and as if we have achieved success. Pretend that we are very surprised, excited, and happy to have achieved stillness and our eyes closed. Even if we have made minimal movements after waking up, it is very important to calmly return to the position we got up from, as if we were reminding ourselves of the command we were supposed to do, then pretend to have woken up and that we managed to stay still with our eyes closed. It is as if we are creating quite a new past, cutting all unfavorable future, and pasting over the present we choose. After this, we are free to return to our daily routine; it is an equally valuable imprint as if we managed to remain still, which will manifest its mechanism in the coming days. Each time we find ourselves having moved upon waking because we forgot to stay still and keep our eyes closed, we repeat the same process—slowly return to bed, as if rewinding a scene in a film, gently lay our head back on the pillow, and with full intention, cut through the timeline of our failure to insert a new reality, one in which we succeeded. We should understand this movement as the cut-copy-paste option of our lucid computer, a way to override the default reaction with the version we consciously choose to reinforce.

Sooner or later, we will come across a second possibility in which we have invested days of effort; one morning, we will wake up and find ourselves staring into the blackness of our eyelids, remaining still, instantly remembering that it should stay that way. It is a truly wonderful moment that will not bring us so close to a lucid dream as it will show us a very clear path—the one we can follow. It will show us that one mechanism is starting to work; it is a special joy that spreads through our being once we realize that our dormant structures are exactly the same as those of others, and that the experience being described will be exactly as ours. We will almost feel that wonderful scent of a lucid dream, which, literally, is only a few tens of seconds away in those moments. However, it is quite certain that at that moment, we will be so euphoric about success, just as we will be the next few times, that we will ultimately wake up due to such euphoria. And that is what we need the least. Our euphoria and increased attention will do to our being what moving the body and opening the eyes do; it will throw us out of a position where we would continue to move lucidly. Body movement is stagnation in a dream, and likewise, movement in a dream implies complete bodily stagnation and stillness. Repeating the affirmation should become our evening routine; in fact, whenever we go to bed, even during an afternoon nap, let it be our habit to repeat to ourselves that we will remember to wake up without moving and opening our eyes. The afternoon nap is the only exception to the rule of avoiding affirmations during the day. It is a hidden goldmine for lucid dreaming attempts, as discussed in my instructions for the Neophyte and later to be revisited in the Practicus grade.

When failure happens, when we move and open our eyes in the morning, or even completely forget about everything and walk to the bathroom, or even leave the house for our morning duties, we should gently tell ourselves what we could have done better, not to correct ourselves but to improve. This is not a reprimand, but encouragement. It is so important to feel the different energy of such guidance. Simply go to the mirror, look yourself in the eyes, and tell yourself that it was a wonderful attempt, but that now we need to push ourselves just a little further—not to succeed, but to try even better, and that everything will be alright. We should be proud of our attempt, not scold ourselves for not reaching the potential given by the affirmation. It is crucial that our magic not fall into that anxious feeling of failure, especially when we have prepared everything carefully, done all as planned, or as someone else claimed brought them miracles, only to find that nothing has happened.

We must understand that “nothing” is a much wider, much deeper gift than we think. That within this failure lies the unrecognized success, which is the beginning of the process or even perhaps the day before the nectar will burst, giving ambrosia that only yesterday tasted bitter, terribly bitter, and spoiled. This is the same liquid that tomorrow will taste the sweetest, with the most wonderful fragrance, and will grant us immortality. But not of the body, rather of the moment in which every pore will be immortal and without decay. Not because it is indestructible, but because it will no longer have the potential to last. It will always be here and now, alive and healthy, without thoughts of tomorrow’s aging. We must learn to accept failure as part of the game. The fact that there is no Angel, that the invocation was clumsily done, is exactly what we need. Why should we experience failure in the invocation any differently than we would experience playing hide and seek? We just have to find the being that has been here the whole time, but has cleverly hidden itself. And the better it is hidden, the better the game. You see how now, the same outcome radiates with a completely different light. Not the gloomy color or shade of failure or loneliness, but the light of approach and encounter. Even when there is no Angel, perhaps it did not hide, maybe we hid from it, and it has been searching for us all along while we sit silently, laughing in the corner of the Universe, trying not to be noticed. Because that is how we agreed, those are the rules of the game, and we find ourselves happy and joyful not when the Angel arrives, but when we remain unnoticed. Its arrival would spoil the game and even bring dissatisfaction. Therefore, everything that happens, every failure, you must feel exactly as that—rules of the game, because it is exactly as it should be, and nothing else.

This important habit, this transition, this journey of the Zelator from the waking state into the state between wakefulness and sleep, which contains nothing of these two worlds except that it is elevated and full of potential, is the rarest, most precious brilliant in the entire spectrum of everything the Aspirant will gain through their diligent work. And what is especially important for us now is that it will perfectly unite the idea of the Moon, the idea of the mind and the magical Dagger, the idea of thought, the idea of passing, and finally, the idea of the Shadow and the “demon on the threshold,” which will be provoked in their ideal environment—the sleep paralysis. So to speak, this cunning practice brings so many other significant achievements for the Zelator; it is like a wild card that sweeps the deck, claiming the strongest hands.

One of the main trump cards in this deck of achievements is the encounter with the previously mentioned Shadow during the sleep paralysis. Many people have experienced this phenomenon once in their lives—an overwhelming fear that arises after waking up, during which we are completely paralyzed, unable to move. This is certainly a hallmark of the REM phase, in which our wakefulness arrives somewhat unexpectedly, like an intruder into the realm of automatic mechanisms that dwell within us, as a result of inherited brain functions from ancient times, something that will be thoroughly explained in the section on sex magick. For that reason, and to avoid redundancy, we will refrain from a detailed examination of the mechanisms and causes behind this phenomenon. What is important for the Zelator is to undergo this experience directly—to step into it, rather than merely contemplate it. The entity that our mind projects and creates within the realm of sleep paralysis—in a sort of mental limbo, which, for the purpose of its assimilation, requires form, volume, and dimension for spatial reasons, wants to meet with us. It wants to step into the light. The only problem that prevents such an encounter is the appearance of overwhelming dread within us, which is merely a side effect of the sleep paralysis, where our primal fears, along with the onset of auditory hallucinations, simultaneously conspire in creating the being of the Shadow.

In general, all experiences in sleep paralysis, or even in the “area” of the Void—when you learn to wriggle out of the paralyzed position of the body, rolling to the side, which is usually always the easiest and most effective way to move out of the physical location and step into the realm of dream—when you find yourself in a very peculiar space of emptiness, without vision but with a clear tactile sense of touch, are tied to the idea of the Shadow, darkness, gloom, or twilight. When you finally achieve vision, you will often, from the area of the Void and sleep paralysis, under the influence of that phantasmagoric, gloomy atmosphere, step into a similar visual scenario: it will be your room in the dark, or any location in twilight, with usually dimmed lights, or mist, with subdued, depressive lighting, and most importantly, a special eerie feeling that will follow you throughout the astral experience. Because that feeling is something you have created, and it immediately projects itself like the clay of the Cosmos into everything around you. In fact, in a lucid dream, as in all other higher, lower, deeper, or subtler planes, you are essentially observing yourself in a quantum mirror, so to speak, and all you see are reflections of a small, fantastic particle of light. All of this is you, with what you have that also prevents you from perceiving that light, which is always and only fear. But not the fear of the darkness, or the eerie emptiness surrounding you, but the fear of the light. Your own light.

This is a realm specifically created for the Zelator and their development. The appearance of the Shadow in the Void or sleep paralysis is like an encounter with the main monster in a film. There is no need to wander aimlessly through the dark halls of this terrifying castle. The punchline of the scenario being played out is the encounter with the dreadful being that resides there. Encountering such a being, which only takes on the cloak and form of the Shadow, provides a completely unique training ground for Will, whose depths and dimensions are entirely fantastic. The phenomenon of the Shadow, also known as the Dweller at the Threshold or the Hat Man, is frequently encountered during episodes of sleep paralysis. This enigmatic figure occupies a liminal space between folklore, psychology, and the supernatural. Typically described as a tall, dark silhouette wearing a wide-brimmed hat, the Shadow has been reported by individuals across cultures and generations. It is more than just a figment of the imagination; it is a recurring presence at the threshold between wakefulness and sleep, where reality blurs and the mind is both vulnerable and alert.

The Shadow often stands at the edge of the bed or in a corner of the room, silently watching with an unsettling stillness. Its mystery lies in its silence and lack of action, which paradoxically amplifies the fear it induces. Although it usually does nothing, its mere presence conveys a threat far more terrifying than any explicit act. It becomes a mirror, reflecting the fears of the subconscious back at the individual, making them more real and immediate. When it does move, it is slow and deliberate, as if it is solely fixated on the Aspirant’s awareness and wakefulness, like a cunning predator stalking its prey. In this figure, more than a mere Shadow, one finds the embodiment of dread itself. Though its form is indistinct, its presence is profoundly felt, as if it carries the weight of countless nightmares. During moments of paralysis, when the boundaries between wakefulness and the dream world blur, the Shadow becomes a manifestation of the mind’s deepest anxieties. The fear it induces is not just of it, but of the helplessness that sleep paralysis engenders—the terror of being trapped in one’s own body, aware but immobile, with only the darkness and this looming figure for company. Some Aspirants perceive the Shadow as a guardian of this liminal space, a sentinel who stands at the boundary between the waking world and the dreamscape. Others view it as a malevolent entity, a demon who exploits the vulnerability of those in sleep paralysis, feeding off their fear and helplessness. This duality adds to the mystique of the Shadow, making it a subject of both fascination and horror. We surely can explain the Shadow as a manifestation of the mind’s attempt to make sense of the paralyzed state. In this view, it is a projection of the mind, a shadowy figure that symbolizes the paralysis itself—a way for the brain to personify the experience of being petrified in fear.

We can observe that phenomena and experiences of alien abduction are often reported in the early morning hours, particularly just before dawn. This timing coincides with the final REM phase of sleep, which is both the longest and the lightest stage. It is well established that REM cycles progressively lengthen throughout the night, with the final one occurring right before waking. During the REM phase, the body experiences intense atonia—muscular paralysis—which can give rise to a peculiar phenomenon: a deeply embodied fear that often takes shape as vivid hallucinations or perceived encounters, such as alien abductions, making this a particularly fertile window for such experiences.

I witnessed when Aspirants, having dedicated their entire lives to the exploration of extraterrestrial phenomena, were struck by intense experiences of sleep paralysis. Instead of the Shadow, their sleep paralysis manifested as a specific horror in the form of mysterious light, often in orange or red hues, radiating from behind windows, doors, and through the gaps of doorways. Accompanied by the sounds of humming and vibrations throughout the entire apartment or house, the Aspirants, like children, especially those raised on a diet of science fiction and alien abduction tales, attributed these experiences to their own abductions by extraterrestrials. Convinced of their otherworldly nature, many devoted their lives to searching for these elusive entities. It was only through our shared practice of lucid dreaming that they began to reencounter these same phenomena, this time almost indistinguishable from the natural occurrence of sleep paralysis. The result was often enlightening for the Aspirants. Although they shattered the myth and even childish belief in extraterrestrial life, they discovered a completely new clue, one that would eventually lead them much closer to the truth. Instead of extraterrestrials and life beyond Earth, they uncovered innermental beings, and the life within their own minds.

All that is needed to encounter the Shadow is to think about it before attempting a lucid dream, preferably before sleep, writing this intention in your action plan. The striking contrast between the ease of making this encounter and the difficulty of enduring the fear that will shatter every atom of the Aspirants being in this phantasmagoric event is astonishing. All the while, as you were reading this, your mind has carefully and insidiously already prepared everything necessary. The idea of the Shadow has already been implanted within you.

Sleep paralysis, often referred to as a state of vibration, naturally occurs after waking without moving or opening the eyes, simply by waiting, doing nothing. In fact, any action in that moment would lead to awakening, and we are heading in the opposite direction. Therefore, wait, but with active anticipation, awaiting any change, remaining quietly attentive to any shift, any sign that something is beginning to stir. It could be a strange humming sound that begins to appear, a peculiar sensation in your body perception, a feeling as though a warm blanket is covering your body, or the sense that you have shifted position, that you are in a different posture from when you first woke up. At that moment, simply remember everything you read here. You do not need to summon the Shadow, but rather, just gently recall the desire to summon it, which is a completely different approach. Remember how you wrote down your wish to meet the Shadow in your action plan before sleep. Never invoke the Shadow—rather, recall the last time you wished to call upon it while awake. That is the entire formula. You will notice that the experience of sleep paralysis changes significantly and transforms according to this recall, this desire for contact with the Shadow, which impacts the course of events like sudden turbulence that immediately affects passengers, who now begin to grip their seat handles more tightly, rolling their eyes and exhibiting fear and insecurity. This is the kind of idea we need, one that inhabits the Aspirant’s mind and acts like poison for the entire experience, changing it to such an extent that everything that happens thereafter in the lucid experience will be perceived through the influence of that powerful and startling current.

After this drastic shift in atmosphere, which will be undeniably felt, the Aspirant should immediately leave the body, distance themselves as quickly as possible from the location of their physical body, and begin constructing a vision. We will not linger here on the ways of doing this, as that would take too much space; all the necessary details about lucid dreaming and astral projection, which contain much more careful and practical guidance for the entire process, can be found within the Neophyte’s Compendium. Once the vision appears, the Aspirant should once again briefly and clearly think about the Shadow, and then pay attention to everything that will begin to happen. In short, the Shadow will come in a way that is uniquely magnificent and terrifying. Writing about all of this in advance would have too much of an impact on the future lucid experience, which would lose its authenticity. Therefore, it is best for the Zelator to experience all of this firsthand and allow the Shadow to manifest in its authentic, unique nature.

However, the entire lesson and the complete instruction that I wish to convey through this collection of words is essentially contained in the fact that one must endure until the end in the experience that will occur once the Shadow manifests. Never give in to the onslaught of that terrifying fear and retreat from the lucid dream by returning to the body. Truly, nothing more than that, which is far from being simple. The trick is for the Zelator to understand all of this as their birthday. Indeed, they are celebrating that lovely day and have invited the entire Cosmos to come—pulsars, black holes, stars, and nebulas, all these magnificent things. They summoned the entirety of existence—the wondrous, the vast, the unknown—to join and have a party. But the Cosmos is slow, it prepares, it tries to carefully and slowly beautify all the darkness from the farthest corners of its existence, to choose, and to buy a proper gift for the Aspirant. And in the midst of all this rush, it decides to send a single being. That one that comes to the birthday party because all the beings in all the worlds simply cannot fit on the guest list is the Shadow. And with it arrives a carefully wrapped gift—fear.

It is certainly necessary to say something about the way the Shadow appears in the lucid experience, once the Aspirant has clearly expressed the intention to see it, sealing that intent by writing it into the action plan the night before going to bed and attempting the lucid dream. No matter how clear and sustainable the scene and vision of the lucid dream may be, full of good and stable energy, the appearance of the Shadow causes a significant heaviness in the experience. Everything slows down; there is a feeling of a completely foreign force watching the Aspirant from behind. A specific rumbling may be felt in the ears and skull, as well as a darkening of the entire scene, as if the atmosphere is electrically charged with a special mental strain woven with terror and dread. If they find themselves in a daylight scenario within their lucid dream, suddenly everything will darken, filled with the atmosphere of autumn gloom, foggy mist, the onset of twilight all around, or perhaps the atmosphere of a pitch-black, silent midnight. That feeling will settle upon the Aspirant—a chilling sense that everything around them simply is, without light, without life, just present, stark, and indifferent. And then, once the mind has prepared the scene for the final act of the play, and all these changes have begun to dull the Aspirant’s consciousness, as an inexplicable dread starts to flow through their being, it will appear.

The appearance of the Shadow is perhaps one of the most authentic encounters with beings and intelligences one may ever face along the Path. I can say this openly—at least in my case, and in the cases of my Students, it has proven true. Simply put, the entire experience is best likened to those teenage years when we would gather after school, rent horror films from the video store, and watch them together, terrified, completely hooked on that feeling of fear. It was the kind of fear that made us want to turn away at the most frightening scenes, yet none of us ever did. No one would leave. No one went home. We stayed, held in place by something we did not understand—but could not resist.

I truly believe it is fitting to mention one of the characteristic and countless experiences I have had, one that I still clearly remember and gained as a young magician through my daily experiments with lucid dreaming, scrying, and astral projection—abilities that have always come easily to me throughout my life, as if they were given to me as natural talents. This experience vividly and satisfyingly conveys the atmosphere of what it was like.

“After finding myself motionless upon waking, I begin with a phantom-like motion, imagining small micro-movements of my head, shifting it forward and backward, as well as swaying it left and right, along with the imagining of falling backward. Within half a minute, I start to hear a buzzing sound—something like a fan, but much subtler. As I continue with these phantom movements, the sound grows louder, taking on the characteristics of a rattlesnake, and an unmistakable fear begins to rise within me, intensifying steadily. The sound becomes more pronounced with each passing second, and soon I hear the unmistakable sound of a massive body crawling on the floor, amplifying my fear further. At last, I roll to the side, emerging from my body and falling from the bed to the floor. I begin to touch my surroundings, moving further from my body. Once I gain vision, I find myself in the hallway of my apartment, surrounded by twilight, with dim light from the lamps that obscures the clarity of the scene. A peculiar weight emanates from this lucid experience, and no matter how hard I try to sharpen my vision or deepen the dream, the sense of heaviness and darkness remains just as pronounced.

I continue to hear the sound of something being dragged along the floor from the next room, slowly approaching my position; simultaneously, the hissing intensifies. Paralyzing fear overwhelms me, rendering me incapable of acting creatively or escaping this dream scene—each passing second, I give legitimacy to this fear by waiting for it in a daze. The sound draws nearer, and I finally notice the shadow at the end of the corridor. I can barely make out anything except that it is colossal. The dragging sound grows louder—now only a few meters away—and suddenly, I see a massive creature before me, as tall as the ceiling—a huge snake nearly a meter wide, its black scales seemingly breathing in a demonic manner, producing a suffocating sound. Instead of a snake’s head, there is the head of an old man with slicked-back black hair, curvy eyes, and an open mouth, emitting that monstrous combination of a rattling hiss and a subtle scream. As if it were a completely independent entity, the fear inside me grows and takes control, rendering me entirely passive in this experience. The horrifying creature hovers over me, its serpent eyes now locked onto mine. Instead of hissing, it begins to scream and howl. Then, the entire vision vanishes, and I return to the physical plane, still conscious, yet holding onto that fear with the same intensity as before. The experience of the fear that dominated my being lingers long after the dream, coloring the entire next day with the same terror.”

This is perhaps the archetypal example of an encounter with the Shadow in a lucid dream—a trial every Zelator must eventually face. However, it is crucial that the Aspirant observes the nature of the mechanism arising in the mind at the moment of the Shadow’s presence, rather than merely undergoing an experience that, while impactful, will inevitably leave a deep imprint and alter their being. At times, it is more important to understand why something appears than to be overwhelmed by its appearance—to realize that the entire fantastic narrative stems from simple processes which, when they intersect, create what we perceive in a particular way. It is more a matter of criminology than mysticism; we must, like detectives, follow the clues without the influence of faith, dogma, hope, or desire. We must approach the entire situation from all angles, as well as from outside every angle, without being biased in any way, and draw a conclusion that often disappoints the frightened child within us. Because, sometimes, from the sound of a street firecracker, we wish to hear the scream of a demon, just as from the reflection of sunlight on a rearview mirror, we long to see the apparition of an Angel. Our fear either blocks such events or leads us into lies and deception, prompting us to accept them as truth out of a desperate need for proof of what we blindly hope for, condemning the one we fear most, rather than the one who committed the act and is the true culprit. In this case, the culprit is us; we are the main architects of this entire masquerade in spirituality. Instead of recognizing that the reflection of the sun on the rearview mirror is just as spiritual and elevated as the light of an Angel, we must accept that, in the end, neither the Angel’s light nor the sun’s reflection will grant us the enlightenment we seek. The encounter with the Shadow is its reversal—an inverted mechanism. We are confronted with everything we fear that this reflection of LVX is “not.” In truth, we are not afraid of the Shadow or sleep paralysis, no matter how strong the fear tied to them might be. Deep down, deep inside, we are afraid that perhaps none of it is real, and that all this strange, dark, black mass is actually our own shadow. That there is nothing there except ourselves, forgetting one very important point. As much as this is our shadow, as much as all these phantasmagorias, all these fantasies about spirituality are merely product of our own eclipse, due to all that fear that this is just our creation, in observing it, we forget that at the other end lies the light, without which our shadow would not exist. But, if the shadow is ours, then whose is the light? This path, this end, this point of the mind, this plane of the Universe is especially meant for the Practicus to locate and for the Philosophus to explore. The Neophyte and the Zelator both break the illusion about the origin and nature of the Shadow. The Practicus and Philosophus finally dare to shatter the last illusion, which holds the entire point and reason for fear. They shatter the illusion of light.

After all that has been exposed, a very pertinent question arises: what should be done with all of this? How should we interact with the Shadow when, in those moments, we are almost frozen, limited by the fear of doing anything other than passively and immobilized, like a victim before a predator, accepting our bitter fate, helpless and powerless before such a strong, primal force?

Just one single thing. Do not wait for that being to approach you, but rather, approach it yourself. Imagine this is the final act of your life, that the cost is your complete destruction, even death. Yet do it as if it were for the sake of the entire Universe and all the beings you love. Do not draw pentagrams before the Shadow. Embrace it. Do not use divine names, nor curses. Instead, hold it firmly and say: “I love you.”

We will notice that this terrifying fear is not truly ours. It is the Shadow’s. We do not fear the Shadow; the Shadow fears us. But as we gaze upon it and recognize ourselves within it, its fear becomes ours. It is a part of our being that has not yet embraced the light, and because of this, it cannot be seen in the mirror, for the light does not reach its surface, and so, there is nothing to reflect. It truly does not know how beautiful it is, how majestic, unique, and magnificent it is. Without a reflection, it cannot know anything special about itself. All the fear and horror that arise in the sleep paralysis, and seep into us with the arrival of the Shadow, is the Shadow’s fear, which only manifests in us because it is our Shadow. Once we understand this, it reveals itself as a creation of light. The fear of darkness is unsettling, but the fear of light and truth is so paralyzing, so terrifying, that it can halt entire Universes in their movement. Make this seemingly traumatic experience a stage and the setting for cosmic splendor. Instead of the twilight and gloom that accompany the arrival of the Shadow, let the darkness be the bearer of a fantastic New Year’s fireworks display. Let that darkness be even darker, so that the fireworks can be seen as vividly as possible. Do not banish the Shadow, do not turn it from you. It is easy, and so boring, since it does this all the time. It has gotten used to retreating from the light. But it is the retreat of your Shadow against your own light. You are not banishing your Shadow with that. You are diminishing your own light. Do not banish. Just say: “Come”. That is the greatest banishment of all: banishment through invocation. There is no cursing, no drawing of pentagrams, no projecting of forces, no vibrating of divine names, no ordering or demanding. There is only loving. There is only accepting. Do not banish the Shadow. Approach, embrace, and say, “I love you.” “Come”—is the greatest banishing, it is the ultimate invocation. Only that.

Turn such a lucid dream into something alive, into a museum of the most magnificent sculpture of the Self. That museum is not a mausoleum, but a living place, a sculpture made of light, where darkness helps the Universe to marvel at it forever, because light is eternal, and therefore that darkness must always be there, forever, eternally.

I want us to carefully consider the nature of this sacred fear, which is so specific that it goes beyond the classic understanding of fear, and delves into the domain of panic, an irrational and abstract blockage of our emotional and mental apparatus, to the point where a dark, terrifying mass of negativity and horror looms over our entire being, causing uncontrollable, panicked behavior within us.

Panic, a word rooted in the ancient Greek god Pan, encapsulates the overwhelming and irrational fear that seizes the mind, often without a clear cause. Pan, the wild od of nature, was known for his unpredictable and untamed nature. As a deity associated with shepherds, flocks, and the untamed wilderness, he was also a god of sudden, intense fear—a fear that seemed to rise out of nowhere, like the wind rustling through a dark, dense forest.

In Greek mythology, Pan was known to instill this kind of terror, known as “panic fear,” in those who wandered into his domain. The sudden silence in the woods, the snap of a twig, or an unseen movement in the underbrush could trigger a visceral reaction, a primal fear that stripped away reason and left the heart racing. This type of fear was believed to be Pan’s presence, a reminder of the wild, uncontrollable forces of nature that lie just beneath the surface of the real world.

Panic fear, then, is not just an ordinary fear but a radical disconnection from the rational mind—a plunge into the chaotic and primal. It is the sensation of being overwhelmed by forces beyond understanding or control, much like encountering Pan himself in the shadowed depths of the forest. This fear can paralyze, disorient, and evoke a flight response, driving one to escape at all costs, even if the threat is imagined rather than real.

Legend has it that Pan’s mother was horrified by his appearance and ran away from him soon after he was born. His father, Hermes, was also afraid of him and refused to acknowledge him as his son. In response to their rejection, the god Zeus allowed Pan to inflict a curse on humanity, causing people to feel sudden, inexplicable fear—a condition that we now know as panic. Pan’s curse was so powerful that it could strike anyone at any time, causing them to feel overwhelmed by fear and anxiety. The ancient Greeks believed that Pan could cause panic attacks in people who wandered too far into the wilderness, away from the safety of civilization.

Is it, therefore, possible that this phenomenon of fear, both panic-stricken and divine, is actually a side effect of arriving at the place of meeting with the light? Is this the applause of “All”—Pan—the Universe, now frantically clapping and congratulating the Aspirant in their final return home after so many Æons spent in foreign lands? Is this feeling of horror actually the sound of thunder, which merely follows the flash of the lightning? No matter how terrifying the thunder is, few fear the light, yet the being does not understand that it is one and the same phenomenon. The phenomenon of enlightenment and the reaction of our remaining being to that light, which it cannot bear, which it cannot look at without turning its gaze elsewhere. And in that gaze away from the light, there is everything but light; that is where darkness lives. From the perspective of the Zelator, darkness is not the absence of light, but the turning away from light. The fear in sleep paralysis is a sign that we have found a passage in the great city, one that takes us quickly to the appointed place of meeting with the beloved, during the thickest rush hour. But this passage is dark, uncharted, and damp. Yet, as long as our beloved is in our mind, we will dare to go through it, for at the end of that darkness is She, who eagerly waits for us and longs for us. Enter the darkness, says the Neophyte, and it is terrifying, justifiably terrifying, without a doubt. Pass through the darkness and come to Her, now radiating with a completely different feeling, and a completely different outcome for the Zelator.

Instead of meeting the Shadow, embrace the Shadow first; let this be your only action point and the goal of the lucid dream. The fear and darkness of sleep paralysis will vanish like dew in the daytime sun, like the drawings we made with our fingers in the winter on a fogged-up kitchen window, while grandmother was preparing lunch. Always keep in mind, constantly and without ceasing: do not fear, this is not your fear. You are not afraid of the Shadow. The Shadow is afraid of you, which is why it creates this fear within you, so you will not reach it. Approach it slowly and embrace it. It has been waiting for this for so long, since your birth.

Dreams are not merely a playground for the Self to engage with—or, more precisely, deceive itself. They also contain certain social elements, rarely discussed and poorly understood, which may have played a crucial role in the development of some branches of our sacred Academy. These elements might have influenced states and phenomena now labeled as paranormal or occult, though they are likely the result of overstimulation and irritation of brain structures that have fallen into disuse with the progress of civilization and the abandonment of certain routines. Not only are these practices no longer performed, but very few records of them remain.

Throughout human history, sleep has been regarded as more than just a physical necessity—it has often been seen as a sacred, mystical experience. Ancient cultures revered sleep, interpreting dreams as divine messages or visions of otherworldly planes. In these nocturnal journeys, the line between the material and spiritual worlds would blur, revealing hidden truths and piercing insights. Different civilizations had their own unique perspectives on sleep. For the Egyptians, it was a time for the soul to commune with the gods, while the Greeks believed it was a state where one could receive prophetic visions. The Romans, ever practical, viewed sleep as a necessary respite from daily toil. During the medieval period, sleep took on a new complexity, as it was often disturbed by beliefs in supernatural entities—spirits and demons that could invade slumber, bringing both terror and enlightenment.

As we entered the modern era, scientific advancements began to demystify sleep, replacing ancient beliefs with neurological explanations. Despite these discoveries, sleep remains an enigmatic frontier, a place where the human mind delves into the unknown, navigating the ethereal landscapes of the unconscious. One of the most fascinating aspects of sleep history is the “two-sleep system,” also known as “segmented sleep,” a pattern that was prevalent before the advent of artificial lighting. Before the Industrial Revolution, it was common for people to sleep in two distinct phases: a “first sleep” followed by a “second sleep.” The first phase began shortly after dusk and lasted for a few hours, after which people would naturally awaken around midnight. This period of wakefulness, lasting an hour or more, was not considered an interruption but rather a natural part of the night’s rhythm.

During this interval, known as “the watch,” people engaged in various activities—some prayed, others read or wrote, and it was not uncommon for couples to use this time for intimacy. The quiet hours of the night were ideal for reflection, contemplation, or magical practices, as the veil between worlds was believed to be thinner. After this interlude, they would return to their “second sleep,” which lasted until dawn. The transition from segmented sleep to the consolidated eight-hour pattern we recognize today was gradual, influenced by the rise of urbanization and the widespread use of artificial lighting. As cities grew and gas lamps illuminated the streets, the need for a broken sleep cycle diminished. The artificial light disrupted the body’s natural rhythms, encouraging people to stay awake longer and sleep in one extended period.

The Industrial Revolution further accelerated this change, imposing rigid schedules that demanded a more uniform sleep pattern. Factory work required a society increasingly oriented around the clock rather than the natural ebb and flow of day and night. The once-sacred midnight wakefulness became unnecessary, even discouraged, as society shifted towards a more utilitarian approach to life. The disappearance of the two-sleep system can be attributed to a combination of technological, social, and economic factors. The introduction of artificial lighting fundamentally changed how people interacted with the night. As the night grew less dark, the need for a segmented sleep pattern faded. The Industrial Revolution, with its demands for increased productivity, further reshaped daily life, imposing a more linear approach to time and sleep.

Yet, beyond these tangible reasons lies a deeper, more seismic shift. The two-sleep system offered a moment of introspection—a liminal space where the mind could wander freely, unburdened by the pressures of the day. In losing this rhythm, we may have also lost a connection to a more primal aspect of our nature, one that saw the night not just as a time for rest, but as a time for quiet communion with the Self and the depths of existence. This historical practice of segmented sleep was well-documented in medieval literature. Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, written between 1387 and 1400, makes reference to it, as does William Baldwin’s Beware the Cat (1561), a satirical work considered by some to be the first novel. The practice also appears in ballads such as “Old Robin of Portingale.” In the upcoming verses of this ballad, we can clearly trace the full concept that we are unfolding:

“…And at the wakening of your first sleepe,

You shall have a hot drink made,

And at the wakening of your next sleepe,

Your sorrows will have a slake…”

Biphasic sleep was not unique to England; it was widely practiced across the preindustrial world. In France, it was known as “premier somme,” and in Italy, “primo sonno.” Evidence of this habit has been found in places as far-flung as Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Australia, South America, and the Middle East. During “the watch,” under the dim glow of the Moon, stars, and oil lamps, people would attend to various tasks. Some tended fires, took remedies, or performed household chores. For peasants, it was a time to return to work, whether checking on animals or completing domestic tasks. Even criminals took advantage of the dark hours, using the cover of night for their nefarious activities.

Religious devotion was also a key component of this nocturnal wakefulness. Christians had elaborate prayers specifically designated for these hours, with one father calling it the most “profitable” time when one could commune with God undisturbed by the world’s distractions. Most of all, “the watch” was a time for socializing and intimacy. After a couple of hours awake, people would return to bed for their “morning” sleep, which might last until dawn or later, depending on when they had first retired for the night. Just as today, the time people finally awoke for good varied, influenced by the rhythms of their first sleep.

At first glance, all of this might seem like another world or an invented story. However, from a temporal perspective, just around the corner, humanity once had a completely different habit that stood in stark contrast to everything we do today, one that altered the entirety of human life to the point of becoming unrecognizable. It is hard to imagine a sphere of human activity that was not affected by this particular way of sleeping, and it is even more fascinating how few records we have of it. This is largely because it was never a concrete event that happened to so distinctly influence humanity. Put plainly, with the advent of artificial light, an entire world subtly and secretly vanished, taking with it many incidental things and customs that once formed the consequences of human thought. From this perspective, they could be attributed to surreal and occult events.

We can only imagine how much more frequent and brutal the experiences of sleep paralysis and lucid dreaming were in those times, as fragmented dreaming was one of the most important methods and a facilitating circumstance, sometimes called the wake-back-to-bed method. This technique requires the Aspirant to sleep for a while, then wake up with an alarm after 4 to 5 hours of sleep, and stay out of bed for a short time, doing light activities that would not overly wake the Aspirant.

Then, they return to bed with the affirmation that they will wake up, remain motionless without opening their eyes, and attempt to exit the body using methods we previously discussed in the last book. This small technical detail greatly helps beginners, even more experienced lucid journeyers, to the extent that success becomes perceived as far easier, and the lucid journeys themselves last longer and differ completely in intensity. Now we can only imagine how many thousands, even hundreds of thousands of people, especially children, had completely normal and frequent lucid dreams as part of their life, and how much the terror of sleep paralysis influenced many to the point that it even became woven into the perception of the world, as well as religious and spiritual beliefs. A completely natural phenomenon that no longer exists, as it has imperceptibly dissipated, may have shaped most of the things we now read about in occultism and spirituality.

However, the much more important question that undoubtedly arises is how many similar occurrences, completely minor, random, even insignificant to be historically recorded, had a drastic impact on the shift and change of our spiritual growth. How many of those subtle social changes, perhaps even biological or astronomical, affected the transformation of our spiritual being to the point that it might have influenced the emergence of occultism, which is, in fact, something utterly simple. A solar eclipse today is a completely normal occurrence, but was it crucial at some earlier moment for a great migration of people that, in itself, carried this phenomenon as something that later turned out to be the most important element of an era, belief, or even social changes? The appearance of a cure for the great diseases that once crippled humanity may have brought about the development of certain hormones and side effects in the body, which generationally completely changed the physiological and even mental aspects of the being. Could it be that Qabalah, Enochian magic, or any other system we believe “works” is merely a subtle confusion of much simpler processes that occurred, yet we have a completely distorted perception of them? So much so that we can no longer follow any traces, so contaminated that we truly do not know not only what happened, but whether it ever happened at all. The example of the dual sleep phenomenon is a perfect example of such a phenomenon, one that many have never even heard of. Just that one small detail, the habit of sleeping in two parts, primarily two hundred years ago, may have forever changed the structure of the REM phase and dreaming, and helped the emergence of lucid dreaming more than all the books and fantasies ever written combined.