Before all spiritual aspirations—before the pursuit of the heights and depths of the Self, a true Aspirant must first be fully embodied, must truly live. The body itself is an essential instrument in the orchestration of Will. Is not the entire Universe the body of God, its limbs woven from constellations, its stars as radiant suns, its cells as molecules and consciousnesses, its vast voids—both known and unknown—moving together as one harmonious whole? And what mind animates such a body? Is it not a singular mind, which, through the veil of division, appears as many? Every mind shaped by man is but a single neuron in this boundless, ultimate consciousness.

Our body, as a microcosm of the divine whole, is not a fixed entity but one that is capable of deep transformation, mirroring the Aspirant’s path through practices such as Asana and Pranayama. Still, can that body grow further, beyond the infinite? Isn’t it always the same? The changes in physicality serve as a fundamental indication of success in Asana and Pranayama. Through the practice of Asana, the Aspirant experiences a shift in their bodily perception; concentrating on the body, one loses the feeling of the body. It becomes distorted, and at times, they may lose all sense of the body’s position. Even though you may know you are seated in a Dragon, you may feel as though you are sitting in a God Asana. This delightful confusion can evolve into a trance of unfathomable proportions, which may or may not lead you off course from the expected outcome. A properly executed Pranayama can induce such miraculous perspiration, leaving an equally remarkable impact on the body, imbuing it with vigor and strength, to the point where the Aspirant might feel as though they have gained the vitality of someone a decade younger. Working with the body changes the body. Yet most importantly, it alters one’s awareness of the body—expanding it toward flexibility, strength, and vitality. There is nothing more refining than a well-executed Pranayama, paired with the effects of an appropriate Asana; nothing brings as much pleasure to the body as such an occasion.

Yet, it is often the case that after apparent success in Asana and Pranayama, the very next day a completely opposite effect occurs—the body aches, the spine hurts, no strength and zeal is radiating from the Aspirant, and as time passes, instead of being energized, they feels nervousness, boredom, and pain. All of this is undoubtedly a significant step forward, and things are going just well. These two opposite experiences, sometimes alternating at shorter and sometimes at exceptionally longer intervals, indicate the same progress. In general, working with the body always has clearly set amplitudes and shifts between positive and negative transfers, and we will witness this mechanism having its foundation in the furthest corners of the Golden Dawn. Too often, pain in Asana is due to a mental attitude alone, which in no way diminishes the amount of neurological pain caused by stretched ligaments. Thus, there is a shift of such positive and negative days in our work. One day, we can sit feeling well, and the other day, sitting is burdened with pain. On the third day, we have already achieved automatic stiffness with sweating. Still, tomorrow, we can no longer sit still for a few minutes due to unbearable itching. In fact, every day is the same, but we cannot perceive that constant, like the difference between thunder and lightning, which are part of the same phenomenon—only thunder occurs later because the sound is simply slower than light.

So, our suffering is hindsight of success that our being wants to portray as pain to justify the appearance of LVX, the presence of success, merging with the body that is one with the soul. Still, we are neither the soul nor that body; we are an objection to that action rejecting both to understand and perceive it in the right way. Even that pain is always just an electrical impulse in your brain, and the moment you feel it, you will know that the real danger has already passed and that it is just an impulse of your flesh that reaches your brain too late. Every time you feel pain, it has already gone. Grab the moment of the onset of pain, and you will see that there is unity with the body as much as Oneness with the Will itself. To transcend this sense is the condition for the ultimate experience. Therefore, the Aspirant’s attention is torn apart by pain, which simply ceases to hurt, losing its purpose when not perceived. What remains is the pure sensation of the pure body–which is always the Oneness and a symbiosis of all the feelings the body endows to the soul. It is an advanced form of orgasm, which has no contractions but presence. The feeling about that body is what contractions and spasms are for an orgasm, which also makes it so pleasing. In this case, there are no contractions in the usual sense of that word. It is just a straight line of ultimate pleasure in the body, in its complete experience of an alive, bright, and constant mechanism.

In our art, there are many practical indications that, through their abundance, seem to nurture the cult of intellect more than the cult of the body. Yet, within our Academy, we carefully cultivate both of these delicate plants with equal attention. For the purpose of their grade, the Zelator must forever discard all meaningless connotations and instructions that bear no relation to the true essence of Asana and Pranayama, and simply separate genuine benefit from mere rubbish. As the Aspirant advances through the grades, they will realize that the entire discipline of Yoga is under siege by a peculiar mental habit—a tendency to transform the simple into the complex, turning the most natural and straightforward achievements into mystical and unintelligible instructions. This is particularly true regarding the phenomena of Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi, as will be evident in the later grades of the Practicus and Philosophus. For the present discussion, however, our focus will be exclusively on exploring the idea of bodily posture and the regulation of Prana through specific breathing techniques.

Understanding the significance of Asana and Pranayama within our program is essential, yet for the Zelator, it is perhaps even more crucial to perceive their relationship—to compare these two practices which are so similar, yet fundamentally distinct. In much the same way, the relationship between Asana and Pranayama mirrors that of the Neophyte and the Zelator. Asana embodies both firmness and suppleness, but its most vital quality lies in its immobility and stillness. Asana is strong and unyielding, while Pranayama is fluid, penetrating, and powerful. The interplay between Asana and Pranayama, like that between the Neophyte and the Zelator, can be most flexibly understood through the epithets of the spheres listed in the book “777,” specifically in column CLXXXVI, which pertains to the afflictions associated with each sphere. For the Neophyte, corresponding to the sphere of Malkuth, the assigned affliction is sterility, while for the Zelator, dwelling in the sphere of Yesod, the affliction is impotence. Grasping these two concepts and understanding why they are attributed to these spheres reveals their inner nature; by describing their relationship, one gains a clearer insight into their essence. The Neophyte in Malkuth, when viewed through the lens of Asana and the idea of sterility, is deprived of the vital spark—no matter how firm or steadfast, this condition remains barren and unproductive. The Zelator, through Pranayama under the influence of Yesod, represents the concept of impotence, indicating an evident lack of structure and the generative power necessary for both procreation and the sexual act itself.

Yet, a Zelator must always remember that the ultimate accomplishment of Asana has nothing to do with the physical body, just as the achievement of Pranayama has nothing to do with the breath. This is an excellent point to briefly revisit the study of the Neophyte and to reaffirm our position on Asana—a position that the Zelator will now refine into mastery.

Asana represents a posture, but such notice requires further details. The nature of this posture is reflected in stamina, firmness, and lightness; in fact, we need to understand Asana as attainment, which contains two components. The first component is purely physiological, making Asana a perfect reflection of a stone statue. But, as a living body is necessarily conditioned by movements of lungs, or the heart, or that, no matter how minor–they always exist, so Asana cannot exist entirely in its absolute sense. Therefore, let us define Asana more flexibly so that every soul can comprehend it. Now, we turn to the second component that can illuminate the choice of an appropriate definition—the mental state. It may seem quite inappropriate to discuss this here, in a place reserved for a strictly physical phenomenon. Yet practice reveals a simple truth: in a perfectly calm body, a perfectly calm mind. But likewise, these factors complement each other. One can deal with the disorders caused by your body in two ways: by killing the body or by killing the attention that defines and maintains the relationship with the body. The ultimate attainment remains the same.

The definition follows from this: Asana is a bodily position that abolishes the consciousness of the body’s existence, but not the existence of consciousness. This is an entirely appropriate definition that has an exclusively practical analogy. Having removed the attention that brings bodily impulses, consciousness is now directed toward goals that are in line with the nature of work. Success in Asana is success in changing consciousness, not the body, although the change in understanding the body is quite obvious. As in Pranayama, the essence lies in the control of an automatic process that represents an eternal burden to attention.

The practice has shown that with intense attention and complete dedication to one thing, that one thing vanishes. In short, it is a simplistic view of Samadhi, but a comparison certainly fits here. If attention is paid to one bodily position, it will soon cease to exist. The condition for this is the continuity of that position; if it changes, the mind will automatically register it as another position, no matter how much logic dictates that it is one. A millimeter of unconscious leaning leads to the definition of movement, so there are no conditions that lead to cessation of attention. This is about conscious statics. The nature of Asana is actually any position, as long as it is one. Pragmatism leads us to supported positions that do not depend on limiting factors, such as muscles or bones. Asana must be one, both spatially and temporally, and it is but one of the steps toward Samadhi. It makes the mind more attentive in a specific way in order to deal more seriously with the problem of one’s own wakefulness.

It would be of great value if the Aspirant, at this stage, made an effort to understand the relationship between secret and surprise. The secret represents the passive Spirit, while the surprise is active. Although neither secret nor surprise directly corresponds to Asana or Pranayama, understanding the relationship between these natures reveals deeper concepts. These are ideas that hold meaning in our minds, in a way that generates other living ideas connected to life and purpose. The Aspirant should know that the notion of meaning is far broader than it may initially seem and should always strive to transcend the ordinary definitions of words. For words themselves do not guarantee meaning. It is through their own meditation and the talent of their contemplative mind that they must uncover and penetrate meaning—their wisdom provides the passage, not their feet. At this point, there is neither them nor their path—only the mind and the points between which they draw lines that awaken into meaningful and recognizable forms, much like the images in coloring books.

In our case, the secret corresponds to the concept of Asana, while the surprise is far more fittingly aligned with Pranayama. Both the idea of the secret and the idea of the surprise arise from a hidden source, yet the secret remains a passive creation, while the surprise is charged with active energy, intimately connected to the will—it is often crafted by linking it to the innermost desires of someone’s soul. Do they want it? Do they love it? The act of preparing a surprise is the younger sibling of the Great Work to such an extent that many are entirely unaware of it. A secret can exist without ever being fulfilled or revealed. The spirit trapped within the magic lamp lingers for a thousand years until it is rubbed—perhaps even by chance. Indeed, there are secrets that remain hidden forever, lost in darkness and oblivion. With surprise, however, the situation is entirely different. It is always directed toward manifestation and revelation. The failure of a surprise lies in passivity—the very quality that suits the nature of a secret. This relationship mirrors the connection between Asana and Pranayama—two limbs of the same body—where the method of their execution may differ entirely, but the idea that sustains them is always the same: Yoga, or Oneness.

The phenomenon of Oneness in Yoga cannot be reduced to mere unity—for there is no union in Yoga. There are no separate things or participants to join together, no two that become one, and therefore no “one” that emerges from duality. Just as in the highest realization of Mahasatipatthana, events do not occur to a participant, nor is any act possible in the presence of a witness. Being one with another is a most inconvenient notion. Each of us feels unity with ourselves in this very moment. Even in the absence of that feeling, our Oneness with ourselves remains indisputable. Why, then, would Unity with another be any different from Unity with yourself? You are one with yourself, with or without that knowledge. With or without “you”, that Oneness is always the same. The Angel holds no affection for the path of Yoga. He does not seek an “other” to become “One.” It is enough for Him to be alone with Himself. Indeed, the Aspirant may become whatever he wishes—but the Angel is only and entirely what He is. The Angel despises the path of Yoga. It does not seek the “other” to be “One.” It is enough for it to be alone with “itself.” Indeed, the Aspirant can be whatever they want. The Angel is “only” what it is.

This is the paradox of Yoga. You cannot practice Yoga. You cannot practice achievement; it would mean that you have already achieved it. Yoga is not even Oneness; it only suggests the attainment of Oneness. It cannot be practiced and, therefore, cannot be more or less attained. Yoga is not a method. Yoga is attainment. What drives you away from Yoga is your practice of Yoga, like exercise and striving are the essence of every failure in our Art.

It is quite unfortunate to define Asana as merely a single step on the path of Yoga. On the contrary, it is but a single stanza in a poem dedicated to the love of God. Even without that stanza, the love itself remains unchanged; even without the poem, that love will still express itself within the heart. The poem is merely the embodiment of a process that already exists—a process that, even if left incomplete, holds the same essential purpose. Whether it takes the form of longing, the eager anticipation of the beloved, youthful infatuation, sensual and enflamed passion, or the childlike adoration of a parent—these are but different manifestations of one exalted and beautiful idea. Every being expresses it in a way that reflects their own maturity and readiness, not only to give that love but also to receive it. Asana is just one form of Yoga—one limb, one hand of a vast organism. Whether we offer it a hand, a warm embrace, or even a kiss, as long as it is a meeting with the Highest, it will be Yoga.

In our holy Academy, we encourage practitioners to approach their Asana with a sense of inquiry and exploration, rather than with rigid adherence to a particular form or technique. We would emphasize the importance of listening to the body and being open to its signals and needs, rather than forcing it into a prescribed posture or sequence. We advise rigid caution against the tendency to use Asana as a means of escape or distraction from deeper psychological or spiritual issues. The Aspirants should avoid understanding Asana as a mere physical practice that aims to prepare the body and mind for meditation, assuming various postures that are intended to facilitate the flow of Prana, or life force energy, through the body.

But how can one prepare for something with which they have no relationship, no certainty that it will ever occur, nor any assurance that it should arrive in the form they expect or hope for? The very notion of preparation is a value cherished by the mind, which, while preparing for one thing, inevitably arrives at another—but never at something as impossible or foreign as the idea of enlightenment. Therefore, let the Aspirant beware of the tendency to “prepare,” to “initiate,” to “open”—any form of introductory or preliminary work that offers nothing but a faint emotional reassurance, a clever yet unconvincing excuse for the exalted Great Work, which remains untouched in its elevated place above their head, while they, like a child, leaps in vain to catch it—fascinated and swept away by a sense of euphoria, as if reaching for some brightly colored balloon.

Everything said thus far is merely a gentle intellectual prelude to something as magnificent as the practical discourse on Asana and Pranayama. The aim is for the Aspirant to understand that the language we use to describe such abstract attainments in Western terms is largely based on limited and superficial associations. In any case, the utmost caution is advised, for intellectualizing these concepts can poison the Aspirant’s mind—entangling them in endless discussions without ever allowing them to experience the exquisite, ineffable fragrance of these truths within their own soul.

Therefore, let us be pragmatic.

It is a beautiful spring day outside. You radiate energy, fully prepared to tackle the practices you have set for yourself. Before you lies an array of meditative exercises and rituals you are eager to perform. You play your favorite music, light an incense stick, and settle into Asana you have chosen—whichever one it may be and whatever it may signify. And now what? Truly, what do you want to do with this? If you go to the gym just to watch your crush working out, it is utterly irrelevant which muscle group you plan to train or whether you should focus on cardio. If you have a little free time and you just want to tighten your glutes, it does not really matter if you go to the high-end gym with a jacuzzi or a mediocre one across from your apartment. Above all, you must know what you seek and what you expect to find.

First and foremost, the Zelator must choose one Asana, adhere to it without change, and maintain it for a significant period. We are not aiming for a random leap into Samadhi; instead, we choose a safer, slower path—the one that more reliably leads us to the goal. The selection of an Asana involves no mystical synchronicities or cosmic alignments. It must rest on a single question: Why do you need this Asana? Is it because you seek physical flexibility and bodily strength, or because it offers exceptional support for meditation and concentration exercises? My personal recommendation is to choose my favorite Asana—the neither-nor Asana—neither comfortable nor unattainable. It should always be one step beyond your current capacity, yet never so distant that it remains out of reach. In this matter, I am quite straightforward and suggest three Asanas: Siddhasana, along with its gentler variant, the God Asana, and the Dragon Asana.

As for Siddhasana, the general consensus is that it is a seated posture. Beyond that, the position of the feet varies depending primarily on personal preference. In the first variation, bend the left leg at the knee. Hold the left foot with your hands, place the heel near the perineum, and rest the sole of the left foot against the inner thigh of the right leg. Then, bend the right leg at the knee and place the right foot over the left ankle, keeping the right heel against the pubic bone. Let the sole of the right foot rest between the thigh and calf of the left leg. The second variation is slightly easier. Here, the Aspirant is instructed to place the right foot in front of the left. Bend the left knee and press the left heel against the perineum, lowering the shin and top of the left foot to the floor. Then, bend the right knee and place the right foot in front of the left ankle, with the outer right heel resting on top of it. The description of these Asanas has been slightly adapted to variations that facilitate easier execution for Western practitioners. Essentially, the provided description is approximately correct, but for greater precision, it can be stated that in the traditional form of Siddhasana, the heels press more firmly against the perineum and the pubic bone.

It is essential to mention a particularly popular variation of this position that visually resembles the lotus and half-lotus positions, commonly known as the “cross-legged seat” or something similar to Sukhasana. In this Asana, the shins are crossed, and the ankles are positioned beneath or slightly in front of the opposite knees. This pose is one we often adopt instinctively when sitting down and is especially favored by children. Although this position indeed resembles Sukhasana, one should be aware of the differences, which, though subtle, still exist. In traditional Sukhasana, the knees should be as close to the floor as possible. Additionally, the ankles are not positioned directly beneath the opposite knees; rather, the legs are gently crossed, with the feet resting on the floor or near the pelvis.

The God Asana is performed while seated on a chair, maintaining all the essential elements of a proper and effective Asana. The spine remains straight, the hands rest gently on the knees, and the knees are bent at a 90-degree angle. One should sit closer to the edge of the chair, ensuring that the neck, spine, and head form a single, unbroken line.

The Dragon Asana is practiced by sitting on the heels with the hands resting in the lap. The shoulder blades remain aligned, and the spine, neck, and head maintain a straight, continuous line, with the chin held level—just as in all other meditative Asanas. In fact, each of these Asanas is designed to position and support the limbs, spine, and neck in a way that allows the body to fully yield to the function of meditation and concentration. This alignment helps the mind quickly transcend physical sensations and focus entirely on inner aspirations.

The mentioned Asanas are the ones I typically recommend to Students, though any other Asana is equally acceptable. I always emphasize, without exception, that it is the Zelator who chooses their Asana, not Superior, just as the Probationer is the one who chooses the practice for their Probation. This choice reflects their duty toward the Light—only they know which Asana serves them best.

All practical observations that follow equally apply to all individual Asanas, with some minor differences that I will address individually. The interference of the Superior in the choice of the Probationer’s practice, as well as the Zelator’s Asana, is poison of the worst kind, which both the Student and the Superior will long excrete in their naive belief that it is all for the benefit of progress. This is the most insidious and terrifying form of interaction in our holy Order, which should be shunned and avoided like the most dreadful pestilence. This is the most insidious and terrifying form of interaction in our holy Order, which should be shunned and avoided like the most dreadful pestilence.

Once the Zelator has chosen the appropriate Asana, the path forward is simple: they must sit and remain perfectly still, moving only as much as is required for essential bodily functions, such as breathing. Yet, from this very moment, a spiritual tempest begins to stir within the Aspirant’s mind, and we must carefully examine each stage of this noble task.

First and foremost, entering Asana should be regarded as locking the body to unlock the mind. This should be done without elaborate preparation, ceremonial displays, incense, or special music. Excessive preparation only triggers the cunning mind’s autoimmune response, preemptively arming it for a subtle counterattack. Thus, even in the most carefully arranged atmosphere, when we are finally alone at home, with music playing and headphones on—one can already sense a decline. The body begins to itch, or perhaps an urgent task long forgotten suddenly reemerges with alarming insistence, compelling us to interrupt Asana. The moment we rise, the phone we neglected to silence inevitably rings. All these disturbances reflect the same underlying neurosis—an unspoken truth that we were never truly ready, deep within, to begin the practice of Asana. Preparing for Asana is like consulting an accountant just before engaging in a sexual act—utterly absurd. The Zelator must learn to act immediately and without hesitation. Asana itself is the preparation for deeper spiritual pursuits; all that is required beforehand is the expression of Will to engage in the practice. A few seconds to sit down, adjust the position of the neck, spine, and chin, and nothing more. Entering Asana must be a swift ambush—no preambles or foolish preliminaries should be granted to the mind. The mind itself is the foreplay in communion with the Holy Guardian Angel, and its nature is but a fleeting morning mist preceding the brilliance of LVX.

Do not prepare. Decide to sit. Sit. Do not move. That is all, truly. We will soon notice that once we become accustomed to beginning Asana—or any other practice—in this manner, the state of mind transforms. It becomes something entirely different, something far more elevated than the restless anticipation we experience when preparing, like a schoolboy nervously walking his first crush home after class. In a way, it is as if the mind is caught off guard. The suddenness of the decision leaves behind a vast, clear, and sterile emptiness—an open stillness in which we now find ourselves. Everything happens so quickly that the usual mechanisms of resistance fail to engage, leaving us with a distinctly different atmosphere—pure, calm, and perfectly suited for the work ahead.

Once we have seated ourselves with firm resolve, locking the body into a position that now resembles a stone statue with our soul trapped within its frozen form, we will soon bear witness to a remarkable phenomenon—the shadowy twin of Asana—that will accompany us for a long time. It is the mind’s struggle to wriggle free from the stillness we have imposed upon it, much like a child squirming to escape a tight embrace that interrupts its play, desperate to break loose and return to its games—its leaps, its restless pulses, its twitches and movements.

A subtle itching and irritation arise, which, in many cases, manifests among Aspirants as a completely misguided response to these disturbances. The treatment of this is similar to a trick that exists in the realm of dieting, when we feel hunger. The vast majority of troubled souls attempt, with all their might, to dismiss the thought of food, believing that hunger will simply vanish. This, however, is entirely the opposite of what actually happens. The more we try not to think about hunger, the hungrier we become. Trying not to think about a particular “thing” is just as active a process as thinking about that “thing,” as long as that “thing” is something we are trying not to think about. However, there is a cunning solution that mirrors what we encounter in our work with Asana. As soon as we feel hunger and the urge to eat, we should intensify that sensation. We must focus all our attention on the hunger that has arisen, striving to feel it to the extreme, to be as hungry as possible, as if we wish to amplify the hunger further and explore what that sensation is truly like. We will be astonished to notice in that moment that hunger dissipates, like condensed fog on a window, when children in the kitchen blow on the glass and excitedly watch it disappear. We will see that hunger is dispelled not by eating, but through concentration and focus. And just like any sensation that disappears once oversaturation occurs, hunger fades when we try to increase it, giving it our full attention. The same principle applies to Asana. When we feel itching and discomfort, we do not divert our attention elsewhere—instead, our attention should encompass and embrace that pulsating sensation of itching and tingling to the fullest. The body will hold onto them for a while, and then they will begin to fade away. We will be amazed as they completely disappear from our perception, as if taken away by a hand—much like the figures we drew on a foggy window as children.

We will witness yet another extraordinary phenomenon. By focusing on the itching, trying to frame and encapsulate it within our mind while holding all our attention on it, we will notice it beginning to dissipate and melt under the warmth of our attention, causing our perception of the body to change. The impression we have of our body might shift significantly, causing us to lose a clear sense of its dimensions and position; it may tilt, grow larger or smaller, and create the sensation of being in a completely different Asana. And what is most important is that we will notice a certain change in our consciousness. As the itching and impulses from our body dissolve, the mind will enter a specific and very pleasant trance. The feeling is unmistakable and very clear, and the more the Aspirant practices Asana, the faster and easier it will be to enter this pleasant state. In a similar way to the practice of lucid dreaming, when we try to enter sleep paralysis and the mind suddenly sends an excruciating itch and urge to move, essentially testing whether it is the right moment to raise the ramp to the REM phase and allow visions to form behind our eyelids, such a barrier is present in our work with Asana. Once we endure, not by fleeing from these pesky and obstructive sensations but by intensifying them, they will fade, releasing all the energy that was held back by that barrier. Now, we will experience a fresh flow and a completely different and altered state of consciousness. With the change in that consciousness, our perception of the body will change as well, as we explained earlier, and the entire process will be very authentic—once experienced, it will always be easily recognizable in future practices, with increasing ease of achievement.

Neurosis in Asana and meditation takes on many forms and phases, each lurking in its own subtle way, compelling the Aspirant to move, to stir, to interrupt—to do something better, something else—anything to escape what, to the ego, feels like a foreign language: continuity, permanence, and Oneness—simply, Yoga. Itching is the mildest and most common occurrence when working with Asana, and it is highly likely that this will be the entirety of the initial disturbances. However, we are all very different mechanisms, and we may be astonished to discover that, in our case, itching and tickling are the least prevalent forms of neurosis. What may befall us next, and it is often the case that in our particular instance the worst cases always arrive, is the very specific urge to move. This is a much more insidious and treacherous mechanism than itching or tingling. The urge to move is so detrimental to stillness, and it can be said that the true affliction for most insomniacs is the inability to remain in one position, the sheer impossibility of existing in stillness. The restless sleeper will turn first to one side, then the other, flip the pillow to the cooler side, open the window for fresh air, rush to the bathroom because they realize they have not relieved themselves fully and still feel discomfort, or get up for a sip of water, creating an endless loop of movement, a chaotic ballet of pulsating urges.

We will mention two other troublesome drives, which are not rare among Aspirants, especially during deeper meditation and trance states: the urge to swallow and discomfort in holding the tongue still and immobile. Both of these issues share the same simple solution, which is easily resolved—by creating a vacuum in the mouth, where the tongue presses against the roof of the mouth, and then, through the teeth, all air is sucked in as if gathering saliva inward. This movement effectively seals the entire oral apparatus, ensuring fixation and stability—physical, but mostly mental and internal, which is the primary factor of discomfort and compulsive urges.

All of these neurotic positions are resolved through the determination to endure stillness, doing the exact opposite of what the urge demands. If we yield to it, the urge only grows more frequent and insistent. Conversely, the discomfort of resisting it is merely the initial challenge—seemingly difficult at first, yet relief follows far more swiftly when we remain firm. This urge is not a true need but rather a childish indulgence towards things we merely think we need—it is the child within us who always desires someone else’s toy, the one just out of reach, rather than being content with what it has, here and now, and in that contentment, all needs and urges would be fulfilled. Once we realize that the child within us does not seek the toy itself, but the joy of play, it ceases to be young and immature. Instead, it becomes a pure spark of light, a fiery star, the fury of life.

One might consider this the first step in our ascent through Asana, or more precisely, a descent into the Self, as the experience of this path is far better described as a downward movement. The mind sinks, diving into its own depths, which more accurately reflects the direction these practices take us. Meanwhile, the body attempts to mislead us with distracting signals, like a baby’s rattle, but when the mind chooses not to follow them, the body responds by adjusting its own mechanics.

Once we settle into Asana with a firm decision not to move an inch, enduring the physical and mental temptations to shift, we arrive at the second stage of Asana, a very refined state in which we begin to lose the sense of the body’s dimensions. This phase can be accelerated with a remarkably effective trick, one I personally apply with great joy. It can also be introduced at the very beginning, drastically reducing the time needed to reach a deeper state while simultaneously expanding the experience to immeasurable dimensions.

Namely, as soon as we settle and lock our body position like a stone statue, at that moment we need to direct all our attention to feel the firm boundaries of our body. We focus on the position we are in, fully invading it with pure attention. While we keep our attention fixed on the outline and contours of the body, and when we dedicate ourselves entirely to the sensations the body gives us, we will notice that the body begins to fade. This can be greatly assisted by breathing, where, with each inhale, we strive to amplify the signal we receive from the body, and with each exhale, we allow that signal to fill the mind’s space, echoing as we enjoy the sensation of the body without overanalyzing anything. Then, again with the inhale, we increase our awareness of the body, focusing on the perimeter, the body’s membrane made up of the skin of the hands and legs, trying to, with each such inhale, amplify the signal sent by the most distant nerve cells in the body. Such breathing quickly produces a subtle tingling exactly where the boundary of our body lies, which represents the line that separates our body from the outer world. This boundary feels like a fine line, perceived as a gentle pulse as we inhale and focus solely on the body. By breathing in this manner, concentrating on the body’s edges and, more importantly, on the sensation the body gives us about its dimensions and position, we quickly enter a unique trance state. The gentleness and beauty of this experience hold a special place in our training. While this state can arise naturally through passive stillness in Asana, employing this breathing trick and concentration on the body, this stage is reached more quickly and much more deeply. Time certainly is not of great importance here, but many things in Yoga are about the economy of movement, especially when Asana is used for purposes such as transferring consciousness into the Body of Light, scrying, or engaging in intricate and deep meditation practices.

Depending on your level of skill, and certainly not exceeding twenty minutes, we enter the third stage of Asana, marked by a complete loss of bodily awareness. The clear sense of physical dimensions and position fades, and where we clearly felt the body when we breathed and concentrated on it with our inhale, now there is an electrified sensation—a fine, warm, and pleasant current, deeply familiar and dear. All that is required here is persistence, and inevitably, the first true response of the body to Asana will emerge—most often a reaction of the muscles, ligaments, and bones to the body’s petrification. The most common response is pain in the spine, usually centered in the lower lumbar region. Unlike the fleeting sensations of itching or discomfort, this pain does the opposite—it intensifies with time. It grows increasingly unbearable until, in the first few attempts, endurance proves impossible. This is entirely normal; the key is to extend each sitting in Asana by at least one minute longer than before. No matter the struggle, no matter the resistance, each new session must last at least one additional minute, even under the gravest of circumstances. In the era of smartphones, where we can easily find a meditation app or a simple alarm to alert us when it is time to stop, it is much more important to work gradually and, no matter how much we think we can sit longer, to limit ourselves to the time we set with our will before the practice—nineteen minutes is nineteen minutes, not a second more, even if, in the twentieth minute, the Angel itself seems poised to bestow Knowledge and Conversation with us. Absolutely not. The body must follow the pace set before Asana; opportunities for improvisation and expanding the practice will certainly come later, during Dharana and Pratyahara. Practice will show that the feeling we can break through the time set for the work is just as much an illusion as the sensation of chills and itching that quickly appear after sitting in Asana, both representing the unrealities of our neurosis, which strikes and refuses to cooperate with the Self. When the time finally comes to extend the practice, we will realize that every extra minute will be desperately needed for disciplines like scrying and astral projection. The ease we once felt—the notion that we could effortlessly prolong the practice—will vanish without a trace, and each additional minute will grow increasingly demanding. Therefore, remain steadfast in the program and advance exactly as prescribed—each time, just one minute longer.

This gradual progression in quantity resembles the Aspirant’s Probation, where the daily repetition of one practice was all that was necessary to move forward; yet, the Aspirant found fantastic ways to distort, change, divert, expand, and enrich that simple instruction, all to alter it, just to shift the course of the great expedition by a meter. And so, instead of reaching the promised land, the crew remains forever lost in the provinces of the ocean, doomed to hunger and oblivion.

The third segment of the practice is certainly the hardest and slowest to overcome. Whether the pain manifests in the back, legs, or neck will largely depend on the chosen Asana, the overall condition of the physical body, and the Zelator’s flexibility. Even with exceptional physical fitness, pain will inevitably arise. It is precisely in this stage that the Zelator will witness a remarkable truth—as the days pass and each session is prolonged by just one minute, the pain will begin to shift and transform. Lumbar discomfort will start migrating up the spine, reaching the mid-back, and within a week or two, it will settle around the shoulder blades and shoulders. If Asana involves crossed legs, the modern lifestyle’s impact—particularly the shortening of the psoas muscles—will bring unbearable discomfort in the groin, accompanied by sharp pain in the ankles, making Half-Lotus or Lotus (traditionally Siddhasana and Padmasana) one of the most dreadful things the Aspirant has ever experienced in their life.

Even when the work is completed, it is never enough to repeat–at every moment and in every place–once the time we set has passed, which is always just a minute, or half a minute, or even just a second more than yesterday, we are met with a new kind of suffering—the exit from Asana. It is as though the imitation of a stone statue has petrified our physical apparatus to the point where it now smoothly and shamelessly refuses to accept the breath of life into it; like Persephone, the body rejects anything of the light of life, constantly leading us toward passivity and the darkness of immobility.

There is something so beautiful in the pain when we return and straighten the joints of the legs, when we move our knees, like waking from a long, thousand-year-old slumber, now becoming aware of the surroundings for the first time; the surge of energy and aliveness from a body that had just moments ago been petrified is always accompanied by indescribable joy. This pain in the joints, knees, and psoas seems to heal and cure, as if, at the same time, it pleases and lubricates those very joints—with a completely subtle kind of energy, and even more importantly, awareness. For pain is always the shadow of awareness, presence, and attention, bringing us insight into the place and time where pain dominates, but equally bringing awareness to the same space and time where the pain unfolds, yet without the one who suffers. The pain in Asana should be viewed and used by a Zelator as a form of Mahasatipatthana, which will be discussed a little later.

Now we can state that up to this segment of the practice, we usually encounter two types of distractions: mental, rooted in neurosis, and physical, at the level of sensation of pain. The first arises from the mind, taking the form of restless, childlike pulsations and disturbances—we feel an overwhelming need to move because the current position does not suit us. A slight shift to the left, then to the right, then back again, until we start questioning whether it is best to return to the initial posture—or perhaps stand up and begin anew with a different Asana. And so it goes on indefinitely. Yet, this distraction can also manifest physically: the body itches, burns, and irritates us—all merely reflections of the inner, restless neurosis that lies at the root of these sensations. The second distraction is physical—primarily pain in the spine, neck, and shoulders. Depending on Asana, additional discomfort may arise in the ligaments of the ankle joint, knee, or groin when sitting with crossed legs. Both forms of distress are overcome through persistence and daily practice.

In practical terms, the Aspirant sits motionless in a single position, attempting to transform the body into a stone statue, striving not to move even an inch. Very quickly, the body begins to react, offering various tricks to make the Aspirant move, and the variations in this are endless–mostly dependent on the inventiveness of the Aspirant’s mind, which devises all these tricks in the form of self-sabotage. It can all begin with a slight itch, which increases in intensity as time passes; this itch can grow to such an extent that the Aspirant is in excruciating torment from not scratching it. However, if they manage to endure, suddenly all the itching disappears completely, and the Aspirant enters the first wave of peace, though it lasts only a very brief moment. After this, they enter the next stage, where the previous irritation from the itch is replaced by a stronger and more insidious opponent–a subtle pain that begins to grow in the lumbar region of the spine, or in the middle part, or even in the upper spine, or the neck. The nature of this pain is flux and instability; it shifts unpredictably, always climbing the spine, serving as both counterpart and antipode to Kundalini. While Kundalini’s ascent brings awakening, this pain, too, leads to awareness—but only as an eventual byproduct. In essence, it is a neurotic assault, a calculated diversion designed to pull the Aspirant away from the path of enlightenment, tempting them to break posture, to move, to stretch, to seek relief. The agony can become so intense that it wrings real tears from the eyes, contorts the being in its grip, and, in the throes of this torment, may drive the Aspirant to abandon the practice entirely. But beyond shifting locations within the body, the nature of this pain also fluctuates in intensity. At times, it builds gradually, starting as a mild ache, barely noticeable, but after ten minutes, it becomes an unbearable assault on the Aspirant’s nervous system. Periodic waves of pain are also possible–after successfully enduring one painful period, a time without pain arrives, and just as the Aspirant thinks they have sailed into the calm harbor of automatic rigidity of Asana, a new, more brutal wave of pain arrives, like a cavalry charge now supporting the previous infantry assault, delivering the final defeat to the Aspirant’s defense. There is no definitive and universal strategy that can adequately prepare the Aspirant for this test, other than patience and persistence.

After each wave of pain and irritation, a deeper and more pleasant wave of peace and numbness follows, in which the Aspirant changes their consciousness, diving inward along the inner trajectory into a deeper trance. These fine waves of pleasantness and irritation, peace and restlessness of the Aspirant’s soul, are reflections of the more tumultuous waves of the great sea of Binah, in which all our neuroses are cradled. Just as the Zelator is successful in Asana, by not moving and remaining motionless, erasing the outline of the body, erasing the perception of the body, refusing to move even an inch, petrified like a stone statue, destroying the very concept of corporeality, “killing” their body, so will the Magister Templi paralyze every cell, every thought of theirs. They will freeze and petrify the entire Universe, destroying the entire existence, erasing the perception of “everything,” erasing the last thing their born being desires–themselves. What is the accomplishment of Asana–the numbness and cessation of the body—that is the Crossing of the Abyss and the cessation (Nirvana) of the Self. Even the liberated man is not welcomed here, as long as they are human, as long as they possess even a trace of Selfhood, a trace of humanity, a trace of freedom. For even the Liberated Adept is not free from their Adeptship—they still face that final and terrible step, the dissolution of the selfness and everything they are. Even our Holy Guardian Angel brings us to this point, but cannot cross the boundary, because even “it” cannot dwell in the solitary towers of the Abyss, for this place is empty and without “anyone.” Indeed, there is “no one” who could live in this dimension.

As the Zelator perseveres in the immobility of Asana, the longer they immerse in the subtle dynamics of the alternation of calm and tension, they eventually reach a moment when these waves cease their play. The soul of the Aspirant then sails into the peaceful waters of the Self. In this state, the Aspirant can dive deep, deeper still, but they reach a boundary where something else must be done, something different, a leap of quality. Something is needed that would move them in an entirely fantastic direction. This is where the next step arises: Pranayama.

Here, we have two completely separate approaches that both yield brilliant results. In one, Pranayama is practiced continuously from the very beginning of Asana, while in the other, it is performed only once the mind enters these peaceful states and attains automatic stillness. Moreover, from this point, there exists a completely separate path, distinct from Asana, which leads the Aspirant into the exploration of inner worlds. A striking shift in the mind occurs through this simple detour–the use of a fixed gaze into the darkness of the eyelids, which quickly manifests the three-dimensionality of the darkness, automatically altering consciousness and deeply intensifying the trance, effortlessly guiding the Aspirant into realms of brilliant visions. This is of particular importance for the Practicus, as we will discuss later. This special method of focusing the gaze complements Asana perfectly, and together, they can guide the Aspirant to such depths and astonishing experiences that they may continue exploring this path for years through dedicated study.

Reaching this level in Asana represents a very important achievement in the training of the Zelator. It could be said that attaining bodily stillness is a prerequisite for nearly all further progress for practitioners of our sacred Academy. Achievements like the transfer of consciousness into the Body of Light, scrying, Enochian visions, and all deeper mystical practices and meditations simply require this step. It would be foolish and meaningless to expect anything without this accomplishment, even though I personally know countless practitioners who have never come close to this stage, simply because they were not persistent enough, or partly because they did not know what to expect—endlessly performing diverse Asanas, transitioning from one pose to another, refusing to understand that the pose itself is entirely irrelevant, as long as it is one.

Throughout my dedicated years of practicing Yoga, and through exploration in the area of Asana, performing special types of breathing which we will discuss later, I have witnessed sudden, sharp movements of the physical body, where it shakes suddenly and briefly, from the torso downward. Together with these jerks and body hops, so-called “frog jumps,” I always noticed they were accompanied by a very specific feeling of happiness, almost a comical state of mind. In fact, it is not even the feeling of happiness that I am referring to, but rather the sense of some internal humor, where the entire being simply grins and laughs, mocking the Universe, attempting to jump out of its boundaries. It is as if the Aspirant’s being has understood the joke of the Universe—that they are a free and conscious individual, possessing something as absurd as free will—that their being begins to chuckle, and from that laughter, starts to tremble and jump. These giddy jumps are the body’s reaction to such laughter. It executes fine hops and jumps, orgasmic pulsations that are not actually part of physical reality, even though the physical body tries to follow them, understanding and laughing at the same joke. They emerge deeply from the Self, which begins to flood every cell and pore of the Aspirant’s body. My lips would always spontaneously form a soft smile, a grin that lit up my entire face. Everything felt amusing, like the school days when a classmate would tell a joke, and the entire class would laugh frantically, most not even hearing the joke, but being encouraged to laugh by the others, now, like a virus of laughter, they all became sick with the same humor. It is hard to say whether this expression of happiness, laughter, and pure joy is a result of reaching deeper levels of Asana, or if it is more of a consequence of the influence of Pranayama on our soul, or both. Still, it often happened that the appearance of giddy jumps occurred without any particular or concrete cycles of Pranayama, simply through perseverance in the stillness of Asana, sometimes even without additional meditations or any other inner work.

Even now, I experience those sudden twitches of the body as a side effect of persevering in the immobility of sitting in Asana, breathing in a uniquely peculiar way—endlessly long inhalations, so long that I forget I am even breathing, plunging the soul into itself, like some pantomime of an Angel imitating a black hole, or the body’s provocation of the Will to turn inward, as if it is the automatic response of the Universe to focus on itself, like a child who initially screams when no toys are around, but when it sees that the parents are not reacting, it suddenly turns to something completely simple—like its fingers or the carpet’s threads, focusing on them and creating a toy from itself. Right at that moment, immense happiness and an utterly unique joy flood the Aspirant’s heart, and they always feel that their lips have slightly curved into a small, barely noticeable smile. Such a movement is often imaginary, but sometimes it spontaneously occurs on the physical lips as well—this movement never disturbs Asana or the principle of stillness, because the Aspirant’s Self has already entered a plane where it has left the conventional relationship with the body and now rushes toward immeasurable distances.

With the onset of body numbness, the Aspirant will realize that this state is far more than mere numbness, as it initially seems. In fact, it is the complete opposite—vitality, in the same way that by staring into the blackness of the eyelids when the eyes are closed, we see that the color is anything but black. It is speckled with light patterns, flashes of violet, green, yellow, and blue. Our entire field of vision is scattered with living vibrations and pulsations of tiny sparkles, creating a true theater of light effects before us, which the Practicus will explore and utilize in their inner investigations in a different way than the Neophyte and Zelator do with lucid dreaming. And just as the blackness of closed eyes completely changes when the Aspirant intensely observes it, transforming that blackness into a completely different array of colors, in the same way, the feeling of embodiment changes during Asana.

As time passes, in persevering with the stillness of Asana, the numbness of the body transforms into the agility and vitality of the mind. The boundaries of the body dissolve, while instead, the Universe now fills with pure energy of presence, the foundation upon which the body was built, from which the Aspirant now only receives a faint indication. As time continues to pass, the sense of energetic fulfillment in which their consciousness resides—where their attention smoothly glides—gains in intensity. At first, they feel the chill of life, as though the body is connected to an electrical circuit. But we want the Aspirant to immerse themselves in such an accomplishment on their own; they must not have excessive expectations nor be prepared for something they have read about and now expect only that, and nothing else. We want them to come to their own experiences, which may be similar or completely different, but again, their own experiences—achieved through just a bit of practice and persistence, with only one condition: they must strive not to allow even a single accidental movement, no matter how small. The Zelator will now recall their work as the Neophyte, when attempting to achieve sleep paralysis, the same condition of immobility of the body, but within a very specific environment where the brain, still believing it is merely a moment of accidental awakening, continues the dream, but this time, it lets a subtle thief sneak into its divine creation of a dream—failing to notice that the Aspirant is, in fact, awake and maintaining consciousness during the transition between the waking state and the state of dreaming.

The Zelator is urged to investigate to the utmost the nature of their sensations once they reach the state of immobility in Asana and the numbness of the body. They must observe their being in these vibrant pulsations as thoroughly as possible, exploring all levels and amplitudes in the waves of this pleasantness. Sometimes, a part of the body is asleep in this divine symphony, and it is necessary to awaken it. We notice that not all parts of the body are equally willing to intonate the hymn to the heavens; rather, there are places with blockages. The mere attention towards these areas is often all that is needed to awaken them. By simply immersing into the bliss of the stillness of Asana, and then enjoying the specific tranquility that radiates from our being during this blessed sitting, I have witnessed many healings in many Aspirants, with various physical illnesses, allergies, weak immune systems, as well as numerous psychosomatic disorders, sleep problems, and let us not even mention lumbar issues—Asana is the deadly enemy of this terrible torment of the modern age.

It is truly necessary to say a few more words about the state that marks this stage. The sensation of the body is no longer a sensation of the body at all, because bodily perception at this stage is not spatial information in the brain, but rather a sense of wholeness with something far beyond the body, which is now merely a pale mathematical unit and the coordinate of energy flowing through the neurological network. In other words, we feel a memory of the body, not the body itself. Or perhaps more accurately: we remember the sensation of the body, which in this state has now been stripped of many hums and white noise, and we now receive a pure signal, just as our Self normally receives it when it is not distracted by trivial matters in daily life. It is as if this beautiful energy now vibrates, waiting for the Will’s command on where and how to be set into motion, expressed, and manifested. It is as if every cell of the Aspirant’s body has awakened from a thousand-year slumber and now pulses joyfully, moving all the other cells, wishing to wake them up like a child who eagerly awakens everyone around them in the morning, already excited for the play that the blessed day will bring. Indeed, it can be said that this state is a fantastic combination of enjoyment and pulsation, like a holy and divine cat purring and squirming before the entire Universe.

If the Aspirant places a grain of rice on a painful or injured area before sitting in Asana, that grain will exert a constant, yet barely noticeable pressure on the attention, which, when the Aspirant reaches the mentioned state, will unerringly focus on that spot, nourishing it with this exceptional energy of awareness, permeating it with light and healing. All the Aspirant needs to do is nothing, simply allowing the grain of rice to do its job—gently distracting and irritating the attention, directing the light of LVX like a traffic light of the Universe. Healing is merely the consequence of attention, which, in turn, is not the result of concentration or visualization, but simply the stimulus from the pressure of the grain on the skin, and nothing more. With this simple trick, I can provide countless fascinating examples of “healing” from my own life, which even my skeptical mind struggles to classify and understand the true mechanism of this physiological-psychological dynamo.

When the Zelator reaches a stage where they feel their body is like a stone statue that, without any muscles or levers, can remain in the same position for millions of years, and around them, in this space of the stone statue’s fulfillment, living pulsations of energy flow and vibrate, it can be said that they will find themselves at a crossroads. They may continue with sitting and deepening their Asana practice, or from this stage, redirect their path toward other spiritual disciplines—such as meditation, scrying, trance, transferring consciousness into the Body of Light, or perhaps other forms of self-exploration. In other words, they will either continue with Asana or use Asana as a springboard to other techniques and achievements that are now closer and more attainable once the stillness of the stone statue and the stillness of the mind have been achieved. As for Asana itself, the Aspirant will continually refine and enrich their performance with small details. With experience and time, they will change the angles of sitting, styles, and types of Asanas, sometimes even inventing their own positions, all in the pursuit of a better and more natural alignment with the state of Oneness in Asana. Simply put, it is like choosing tires for your car; if you live in mountainous areas, you will give up on summer tires, no matter how discounted they are; while some may completely give up driving if it is more practical for their life to ride a bike or take public transportation. Asana is exactly that—transportation to the destination. Without knowledge of the destination, everything is irrelevant, and any further discussion is meaningless and fruitless. The ultimate destination, our goal that will only be supported and eased by Asana, is the true and final destination, and it is itself the only position—not of the body, but of the Self. What a posture in Asana is for the body, that is Asana for the Selfhood. A Zelator must always keep in mind that sitting in the petrified Asana shakes their flexible soul.

It is quite convenient to mention some practical pointers and ideas that might be helpful for a Zelator. They often sneak into our minds during philosophical contemplations, causing us to forget those small yet immensely useful tips and inventive ideas that enrich practice. More importantly, they inspire the Aspirant to experiment, rather than rigidly adhere to instructions and rules set down by those who came before. A written recipe is not inherently nourishing—what is a remedy for one may be poison for another, whether in dosage or composition. Sometimes, a simple shift in practice, a slight change in perspective, or the gentle pulse of an instinct born from the childlike mind can transform a rigid structure into a living, breathing work of art—a divine counterpoint between the Self and its unfolding. This inventive flexibility, this fluid adaptation in execution, is the only true measure that, in the hands of the Aspirant, can turn what first appears as an arbitrary discipline into a genuine path toward the Great Work. A path they will walk with confidence, not just once, but there and back again—each time tracing it with greater clarity, so that others, too, may follow that winding yet unmistakable road toward the ultimate destination.

We will go through the same postures I mentioned at the beginning, but now enriched with personal observations and details that are the fruit of my own practice, without overly prescribing or insisting that anyone follow my exact approach. Not at all. This is merely an example of how a clear instruction or explanation can, in itself, contain numerous subtle interpretations that may evolve into a form of meditation and self-observation, which is particularly suited for this grade.

The God Asana—this posture is often beloved by beginners on the path. Many consider it the easiest, since the posture requires no bending of the ankle or knee joints, so an inexperienced mind may underestimate it, dismissing it as unremarkable and insufficiently similar to those worn-out photos of fakirs and gurus sitting with crossed legs and twisted eyes. Its simplicity is undeniable, yet there is so much to be said about such a magnificent position. It recalls the posture of Egyptian gods sitting; its monumental quality gives us a sense of granite-like permanence, one that defies time and change, while retaining the inner wisdom to move within that space, to live, to expand, and to resist external influence, hermetically sealed within a divine shell. I must express that it is one of my favorite positions, in which I have spent years of successful practice, and whose simplicity in no way diminishes its brilliant impact on my achievements. I would like to touch on some details in the execution of this Asana, which are worth considering before beginning practical execution.

Regarding the position of the legs, there are three approaches. The first is to keep the feet parallel and hip-width apart, which creates a mild, almost imperceptible tension in the hips for those with lumbar issues, which may only be felt after long periods of sitting in Asana. The second method is to slightly rotate the feet outward, at a gentle angle, which causes the hips to widen and open outward. In this case, the feet stand wider than the hips, giving a feeling of greater stability and tranquility. In both variations, the knees form a 90-degree angle. The third, more traditional, method is to keep the legs together with the feet pressed against each other, parallel.

The hands rest gently in the lap, and this will be discussed further, as the subtleties in the execution are where the differences in success lie. Regarding the hand position, there are also certain variations that must align with the appropriate leg position. Certainly, the feeling of comfort in the Aspirant will be the infallible measure, guiding the combinations in the most optimal way. The Aspirant should first explore the comfort that arises when holding the hands in the center of the lap. Then, let the hands slide forward toward the knees, feeling for their own comfort, whether it feels better when the hands are closer to the knees or hips. Sometimes, the hands might embrace the knees to see if this feels right. Then, conversely, from the center, the hands should be pulled back toward the hips, in a way reminiscent of samurai sitting. The palms should gently turn inward, while the elbows open and spread outward. The thumbs should be slightly apart, facing each other; in this way, the line extending from the outstretched fingers of both hands and the thumbs will form a triangle. Also, the Aspirant should explore the completely opposite hand position; that is, first placing the hands in the center, then gently moving them toward the outer thighs. Then, repeat this by sliding them toward the inner thighs. It is essential to go through all positions and discover where your uniqueness and comfort lie. We should not assume or imagine in advance how a certain position might feel after sitting for hours, but rather try to feel it for ourselves, and determine whether it is comfortable or not.

Discovering the ideal position in an Asana is a crucial part of the exploration in Yoga. Over time, the Aspirant will adjust the technique so thoroughly to suit their own execution that it will gradually evolve, bearing little resemblance to the initial attempts. This search is like feeling in the dark; we do not know where we are headed, but we trust that we will reach somewhere, always, and only, on the condition that we never remain in the same place. Instead, we must keep changing, keep exploring, and keep sensing until we find the handle that leads us to the exit. This is such an exalted habit that should adorn every discipline in our program, not just applying techniques that we like, but also changing the techniques as we like.

This Asana has a subtle and deceptive tendency for the body to bend at the shoulders, making the posture, which we are convinced is perfect for the spine, suddenly reveal itself to be hunched. The only true remedy for the tendency of the body, which manifests in all Asanas when the body leans forward, the shoulder blades arch, and the chest contracts, lies in a mental trick. The trick is to sit as though we have fallen from a height, and now, having anchored and rooted into the position, we imagine that the pressure of the Universe is compressing the entire body like a snowball. At first, the entire body was like scattered and loose snow, but under pressure, we now compact it into a solid, perfectly stable snowball. No matter how we press it onto the ground, it will remain that way. The mental pressure that compacts the body must be triggered, just as when we create a sandcastle, using the pressure of our hands to shape a mass that stands firm. Another effective trick is to imagine that someone has gathered all our hair into a bun, which is then hung on a hook in the ceiling above us. We should imagine and “feel” that our neck and spine are now hanging from a thread of light connecting us to the heavens, and now our body, like a cat, purrs softly on that thread, delighting in that unmovable fixation.

The positioning of the fingers is also very important. They can rest in the lap, gathered together, where the thumb forms a right angle with the other four fingers. Some Aspirants find it more comfortable when all five fingers are slightly spread out, with almost identical spacing between them. The key instruction is that no position should be under tension, whether physical or mental. Instead, everything should be relaxed, yet still “stand on its own”—or more accurately, hang on its own. Remember the trick we mentioned, where you imagine your hair being hung from a hook directly above your head. It is only that thought, which should gently press our attention during the practice of Asana, that subtle, imperceptible intention which sometimes does everything needed to prevent the body from wriggling and overcoming the mind, which, by pursuing it, distances itself from the ultimate and only goal of Oneness.

In conclusion, it is essential to emphasize that this Asana is performed while sitting at the edge of a chair. Like children who mischievously rock back and forth during lessons, moving forward and backward on the front two legs of the chair, they perfectly demonstrate how a young soul instinctively reaches for the stars. It is as if they unconsciously set the spine correctly, in line with the neck and head, in an action that adults often scold and criticize, yet it hides the essence of the God Asana, where the Aspirant is grounded in the spine, and repeating again, infinitely many times–like being hung by the hair, gathered in a large bun, on a hook directly above the head, like a lion observing the boundless prairie, watching over its pack, while also awaiting prey, ever vigilant, ever attentive.

The Dragon Asana is my second favorite Asana, which I also enthusiastically recommend to my Students and use more frequently as the years go by. It is also widely accepted, both by beginners and more experienced Aspirants. It can be said that all the comments we made regarding the God Asana apply to the Dragon as well. The positioning of the arms is crucial here, as the body’s tendency to curve is even more pronounced in this Asana. If the arms rest closer to the hips, it seems that the Aspirant’s posture becomes much more promising. This arm position sometimes requires the legs to be slightly spread and the knees to be opened outward. If, on the other hand, the legs are kept parallel and together, the arms will follow the same approach: palms of the hands facing each other with the fingers gathered. Many practitioners will pull their arms closer to their hips, toward themselves, in order to allow for a proper spine and a more stable position. If the legs are spread into a V shape, with the knees moving outward, the palms will turn in the opposite direction in the lap–the fingers point inward, which will move the elbows outward. The Aspirant must always have the sensation of being suspended from the top of the head, as if having gathered the hair into a bun, and now that braided bun is hung on a hook directly above their head, as we mentioned earlier. In this Asana, it is necessary to sit on a firm surface, without a cushion, though it is quite possible that this will harm the knees. Therefore, a compromise solution is to sit on a carpet or a Yoga mat. The Aspirant must always be prepared for the tendency of the body to lean forward and the chest to collapse inward; the most effective counteraction is to subtly tilt the head backward. Sitting should not rely on the engagement of any muscle.

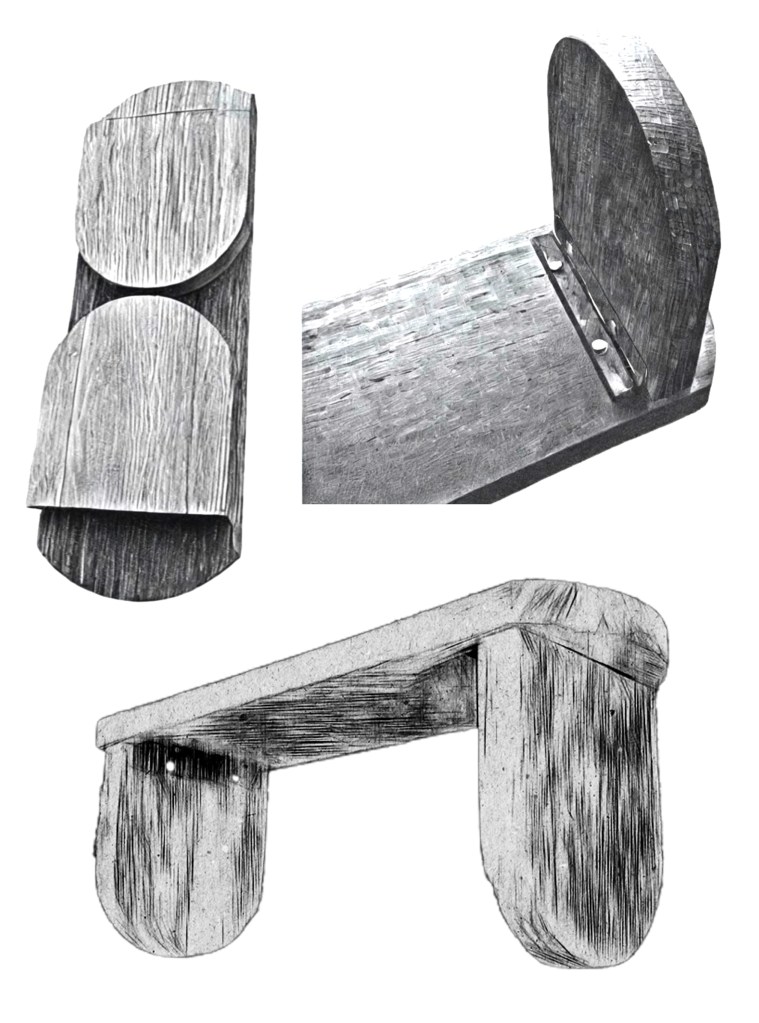

Along with this Asana, I will take the liberty to present my own way of performing the entire practice, as I have been doing for years, which allows me to remain in the stillness of Asana long enough to satisfy every inner work; whether it is a form of deep meditation, the execution of something as sophisticated as the Body of Light technique, or an experiment in Enochian magic. For this purpose, I have constructed a special meditation bench, which, with its uniqueness, allows the spine, neck, and head to align in one straight line, as if mounted upon an invisible axis. This specificity lies in the idea that it enables me to sit slightly leaning forward, which causes the much-needed opening in the hips, while the center of gravity in my body shapes and adjusts the position to its finest details. All I truly need to do is sit on my bench and allow my body to naturally tilt and lean forward; the legs, which are semicircular in shape, allow the entire body to slide forward enough to open the hips, while the spine, neck, and head synchronize into one alignment, yet not enough for them to fall forward. I am quite certain that everything will be much clearer when you see the design of the bench; it is enough for any Aspirant to simply sit down without much thought, as this process is so devilishly automatic that the body will naturally find the position it needs for the work.

This aid must never become a substitute or a means of making Asana easier to attain, as its mastery must rely solely on the body, without dependence on supports or any form of external relief. A meditation bench is undoubtedly a valuable tool for deepening meditative states, but it must never assume a primary or privileged role. It serves as assistance, not as an accomplishment in itself.

Certainly, working with Asana does not exclude working with the other layers of our being. We must protect and distance ourselves from tendencies that equate Asana with Hatha Yoga, as sources of the most dreadful infections. Every argument with them scatters a special allergy throughout Tiphareth, like mold that consumes the Tree of Life, and the plague of the Self.

The Aspirant must always keep in mind that the variant or form of Asana itself does not guarantee anything beyond stretching and physical benefits. For deeper meditation and reaching higher states of consciousness, it is sometimes much more purposeful to choose an easier Asana. Our restless mind so desperately wants enlightenment to depend on the day of the week, the alignment of the stars, the color of the walls, or the direction in which the altar faces, rather than on the most crucial factor in our entire program–ourselves. That unmistakable inner sense of satisfaction when we settle into the right position. The way we instinctively turn to the side that feels best when lying down. The way we order food that makes our mouths water. The way our gaze naturally follows the type of woman that draws us in. Always, and in the same way—toward whatever makes us smile. Without anything being funny.

So much more could be said about this beautiful topic. It has been briefly mentioned before, but I am not hesitant to repeat it: does the type of position, or the type of Asana, really matter? This certainly depends on what Asana is being used for. Therefore, most Aspirants cannot expect success in Dharana in full Lotus as much as they would in the much simpler “Dragon” or even more so “God,” simply because these Asanas are incomparably easier for the ligaments of most Westerners. Perhaps for the first half hour, there is not much difference, especially if you are a dedicated practitioner. But after an hour, even Half Lotus grows uncomfortable, and every trace of pain or strain becomes a hindrance, pulling the Aspirant away from the journey into the depths of the Self. If our goal lies within the domain of Hatha Yoga, then stretching and bodily refinement find their highest purpose in the Lotus posture—where the weight and discomfort of Asana transform into a source of joy. The Aspirant perceives, within the very pain, the body’s subtle language, signaling renewal, vitality, and expansion. With each passing day, they prolong their time in Asana, and these gradual extensions shape their mood. They persist, they conquer, they attain spiritual triumph—each day adding another measure, another minute more. Soon, their body gains not only flexibility in Asana but in all aspects of life. Movement, diet, even sexual expression, become more effortless, as the body itself grows lighter, more aware, and deeply fulfilled.

However, if the Aspirant is striving for Pratyahara, Dharana, and Dhyana, there is certainly no need to waste precious energy and time on something that will not contribute to the success of achieving such deeper meditative states. Personally, I have spent a long time investigating the belief that the form of Asana is causally linked to the inner achievement of Dhyana and Samadhi, but the more I experimented and recorded results, the more I abandoned the desire to connect these things. In truth, any attempt to systematize Samadhi—whether through logical constructs, structured methods, or deliberate projections—is bound to fail. Simply put, both enlightenment and the Holy Guardian Angel in our program hold no real value, while our mind will do everything in its power to somehow insert and push them into its coordinate system, giving them a value that, to it, seems close to reality–but it is something that is not real at all. This is certainly a completely separate topic that the Aspirant will inevitably engage with in later grades, but for the purpose of the Zelator’s achievement, it holds no particular significance. Truly, the Holy Guardian Angel is neither real nor possible, but because of it, everything else becomes so.